VINCE SKELLY: RITUALS IN WOOD

Photography by Justin Chung and courtesy of Vince Skelly

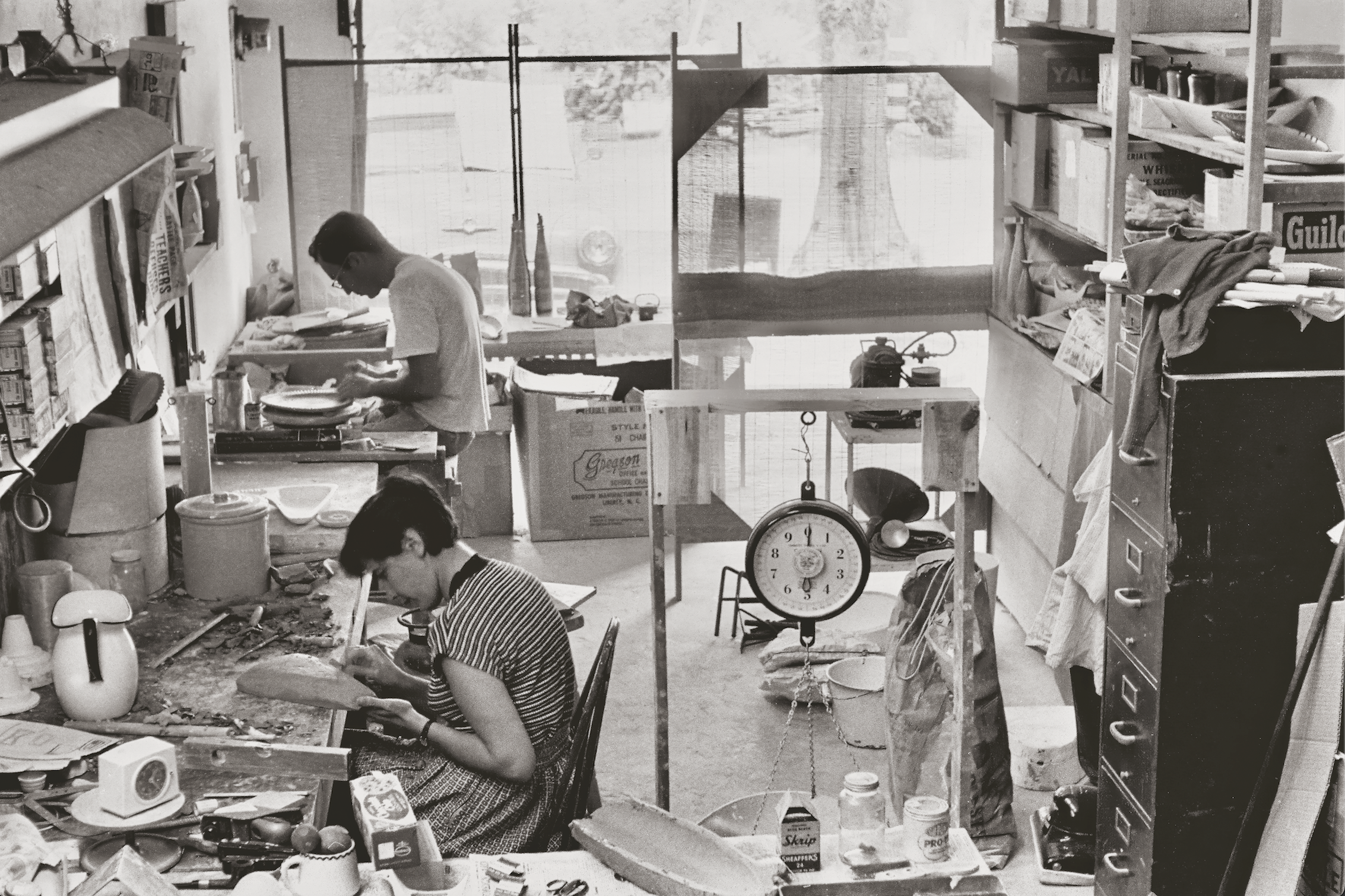

For Vince Skelly, carving is not only a process – it’s a vocabulary. In Material Curiosity by Design at Craft Contemporary in Los Angeles, his newest suite of carved wood sculptures builds on a lineage that traces from megalithic structures to Brancusi to California craft, all filtered through improvisation and a chainsaw. Presented alongside the work of midcentury design visionaries Evelyn and Jerome Ackerman – whose collaborations across ceramics, mosaics, textiles, and wood redefined accessible modern aesthetics – Skelly’s contributions anchor a multi-generational dialogue about how we make and live with objects today.

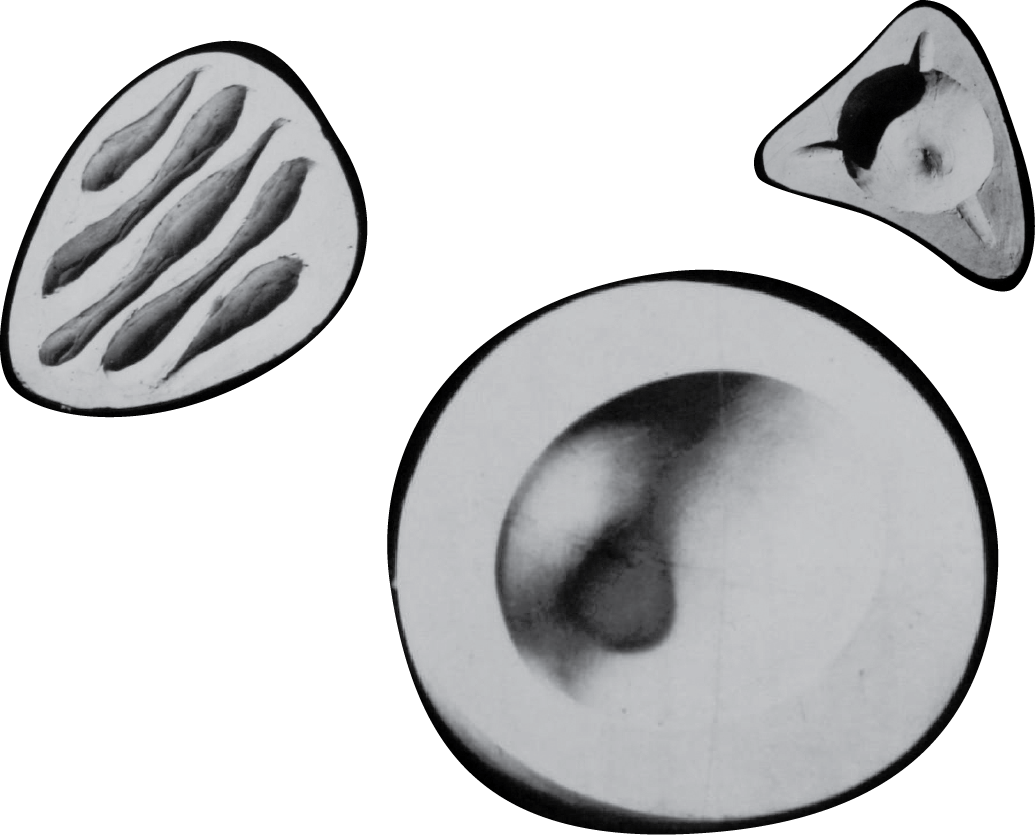

The exhibition, which runs November 15, 2025 through May 10, 2026, brings Skelly’s work into conversation with fellow California-based artists Porfirio Gutiérrez and Jolie Ngo, each exploring material transformation through their own cultural lenses. Set within a vibrant collection of over 100 works by the Ackermans, Skelly debuts four new carved pieces – a bench, a chair, an offering bowl, and his first-ever bookcase – that blur the line between sculpture and furniture, function and ritual. His presence extends further into a two-part Makers-in-Residence installation opening February 2026, where visitors will encounter sketches, maquettes, wall works, tools, and a bronze chess set that together offer an intimate, process-driven portrait of the studio as sculpture.

Ahead of that activation, we spoke with Skelly about tool marks as language, the quiet usefulness of an offering bowl, and what it means to keep the rawness of the studio alive within a museum context.

BENCH BY VINCE SKELLY. PHOTOGRAPHY BY JUSTIN CHUNG.

Materia: You’ve described your approach as “embracing the idiosyncrasies of the material.” Can you share a recent moment in which the wood itself guided or redirected your creative process?

Vince Skelly: I created a sculptural bench for an elementary school, carved from a raw log with inherent forms that naturally invite play and seating. My design philosophy was one of minimal intervention, aiming to highlight the log’s naturally formed cradle without obscuring its character. This was achieved through a subtle, fluted texture that gently funnels attention toward the center. Leveraging the log’s complex, organic surface, the final additions were limited to a few polished seating planes and carved step details to define clear entry points for young users.

Materia: Your tool marks are intentionally left visible – almost like a record of gesture. How do you think about trace and imperfection as part of the language of your pieces?

VS: The marks are evidence of time spent, of rhythm and hesitation. I think of them as fingerprints rather than flaws. Each cut records a decision, and together they allow the process to be more transparent. I’m not interested in sanding all those traces away because they give the work a sense of presence and honesty – something that connects more to ancient processes and human touch than to machine perfection.

Materia: The show invites viewers to consider design as both an aesthetic and investigative act. What kinds of questions are you investigating through your objects?

VS: I’m always circling questions about how we live with objects – how they shape our daily rituals, and what emotional charge they can carry. I think about the balance between sculpture and function, between something that’s meant to be used and something that’s meant to be contemplated. Each piece becomes an investigation into how form, material, and use can coexist without hierarchy.

Materia: The offering bowl reflects your idea of a domestic altar – a place for daily deposits. What inspired this notion of ritual within everyday life?

VS: I was drawn to woodworking from an early age. My childhood house was filled with handmade things. The idea of the Bowl came from my own habits in the studio. I kept putting my keys, notebook, and scraps of wood in the same spot every day, and it struck me how small actions like that form quiet rituals. I wanted to design something that acknowledges those gestures – a vessel that gives them weight and intention. For me, it’s about honoring the mundane.

Materia: Your upcoming Makers-in-Residence installation will reconstruct elements of your studio within the museum. What do you hope visitors will take away from seeing your tools, sketches, and process in situ?

VS: I hope people see that the work is as much about process and that you can make things with a very limited tool kit. There’s a very low barrier for entry into this type of making. My studio is a living environment – dusty, improvised, full of experiments and abandoned “halfway” sculptures. By recreating parts of that within the museum, I want to highlight the importance of experimentation and play. The most exciting part of the process is the flow from one idea to the next. Seeing the raw wood, the chainsaw, the maquettes – it allows people to connect the physical labor and intuition behind the finished forms.

Materia: The inclusion of smaller experimental works and a cast bronze chess set introduces new materials and scales. What excites you about expanding your sculptural vocabulary?

VS: Working in new materials always opens up different ways of thinking. The bronze chess set, for instance, started as a way to translate my carving language into something cast and enduring – on a much smaller scale. The chess set has a different, more playful utility than my previous work.

Materia: Your work often references ancient carving traditions and modernist sculpture alike – from dolmens to Brancusi. How do you situate yourself within this continuum?

VS: I’m inspired by primitive objects and megalithic structures – forms that feel both ancient and somehow completely at home in the modern world. I like that the construction of dolmens is explicitly transparent and simple. Brancusi and JB Blunk are also sources of inspiration. I see myself as part of a long lineage of makers.

Materia: You speak of “tension between the ancient and the modern.” How does that tension manifest in your current practice- formally, emotionally, or conceptually?

VS: Formally, it’s in the simplicity of shapes – objects that could exist in a prehistoric site or a modern living room. Emotionally, the tension manifests as a pervasive sense of nostalgia – not for a specific past, but for the primordial experience of making and connecting. This isn’t just aesthetic; it’s a visceral yearning for the ancient human hand. Conceptually, it’s about honoring instinct and imperfection in a world obsessed with polish. I’m trying to build bridges between those extremes.

ACKERMANS STUDIO. ARCHIVAL IMAGERY.

Materia: How do you see the role of handcraft today, especially within a design world increasingly defined by digital fabrication and efficiency?

VS: Handcraft carries a kind of slowness that feels radical now. In an era of replication and speed, the handmade object reminds us of care, imperfection, and individuality. It’s becoming increasingly more noticeable and special.

Materia: Finally, as you step into this next chapter – museum exhibition, residency, new scale – what questions are you asking yourself as an artist?

VS: I’m asking how to stay open. How to evolve without losing the rawness that drew me to carving in the first place. How to create work that still feels curious, not formulaic. This exhibition has pushed me toward new forms, like the bookcase, and I want to keep following that edge.