CROSSING CURRENTS, A CONVERSATION ON ARCHITECTURE AND ITS VIOLENT INTERACTIONS WITH CULTURE

Photography courtesy of the artists

Ouroboros Film and Stills, 2017, Courtesy of the Artist and Imane Farès, Paris.

Crossing Currents was a two-day screening program featuring 14 video artworks and films curated by Samantha Ozer that recently took place at Galerie Nordenhake in México City. It was the gallery’s first time hosting a video and film series and was one of the first programs to be shown in their new Roma Norte space designed by architect Frida Escobedo. The program is a conversation about the architecture of built spaces and its violent interactions with environment and culture. Samantha discovered many of the artists during studio visits and recognized a theme she had been ruminating on—the relationship between city and country, how over the last two decades architecture was not acknowledging the effect that buildings have on urban design, social life and the creation of an identity. “Our environment affects the way we view ourselves and the way we interact with other people“. This group of 14 artists tease out these relationships through poetic narrative to violent reality, addressing what Ozer describes as ‘cycles of trauma’.

The night of the second screening, Samantha Ozer, whose work revolves around art and design concerns, sat down with MATERIA Editor, Sarah Len to understand how this ambitious project came about and how it relates to a humanistic approach to architecture and design. The story below is an adaptation of the conversation.

In the pandemic, we saw many people who had access and the ability to leave cities begin an exodus to what we think of as the countryside. Within this, there emerged a discourse of cities being dangerous, infectious, and dark and the countryside as being safe and lush, with more space and air—a true pastoral imaginary. While this romanticized vision exists in some places, the countryside is also the space of deforestation, fracking, mining, factory farming, imminent urbanization and countless other forms of resource extraction, in which humans often engage with other species violently. In many ways, the pandemic is a symptom of this ecological crisis—an environmental attitude of exploitation in which lines are drawn between the idea of human and ecological space, with humans placed at the center. Nevertheless, these zones are not discrete. Humans and their homes exist within entangled ecosystems that implicate non-human actors as well as peri-urban and rural expanse.

For the screening program, I wanted to bring together a group of fourteen international artists—Basma Alsharif, Kiluanji Kia Henda, Garush Melkonyan, Laura Huertas Millán, Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Fernando Ocaña (in collaboration with Alejandro Veneno), Karrabing Film Collective, Luiz Roque, WangShui, Himali Singh Soin, Kandis Williams, Tania Ximena, Yang Fudong. They add more nuance into our conception of the relationship between the built and natural environment, the traffic between city and countryside, and the embattled ideological currents circulating through this multi-form flow. The program takes a narrative journey through five thematic threads—existing or “inherited” mythologies that we have of nature and how this leads to the construction of personal identity, the emotional experience and methods for communicating across different landscapes, motion and memory to explore the presence and disappearance of culture and natural resources, the human and non-human actors whose labor and survival are directly influenced by resource exploitation, and alternative visions of life in the face of an ecologically devastated planet.

In terms of architecture and design, across all of these works is an underlying awareness and argument that the built environment holds great power. More specifically, architecture does not exist in a vacuum. Buildings and their networked connections on the scale of urbanism determine how we move, dictate our proximity to other species and nature, and affect our construction of ourselves and how we interact with other humans. Our surroundings shift our personal and collective identities and are representative of what we value, in terms of quality of life but also culture. In From Its Mouth Came a River of High-End Residential Appliances (2018), WangShui composes a narrative that entangles their identity with the architecture of the Hong Kong skyline. Traversing the landscape of the Residence Bel-Air, a luxury waterfront apartment complex, the artist narrates the journey of flying a drone through the designed holes in the center of each building. The voids align with feng shui principles and also allow dragons to fly from the hills and drink from the sea. In a city where residential real estate garners up to $200,000 per square foot, it is a powerful testament that historical mythologies and a belief, natural balance, and design aesthetics were privileged over profit.

While WangShui offers a more poetic reading on the idea that there is no absolute end or beginning to the city and its supposedly peripheral exterior, Karrabing Film Collective presents a violent reality. An indigenous media group native to Australia’s Northern territories, Karrabing Film Collective’s creative output centers around addressing the legacies of colonial violence and current conditions of exploitation at the hands of state and corporate powers. Windjarrameru (The Stealing C*nt$) (2015) is the scripted story of a group of indigenous young men who miners falsely accused of stealing beer. While the miners are illegally sampling iron ore close to a sacred site, the boys are forced to hide out in a “chemically compromised” mangrove, in which they risk adverse health effects or arrest. In extracting building materials, the natural environment and the lives of those in rural areas has been violated. This story is part of a larger narrative in which the waste and chemical toxins that are produced in densely populated areas and emitted in the countryside are recycled back through food and water systems, all while disrupting local and Indigenous communities. Natural resources that are extracted without proper consideration for sustainability threaten survival and contribute to chronic ecological disasters.

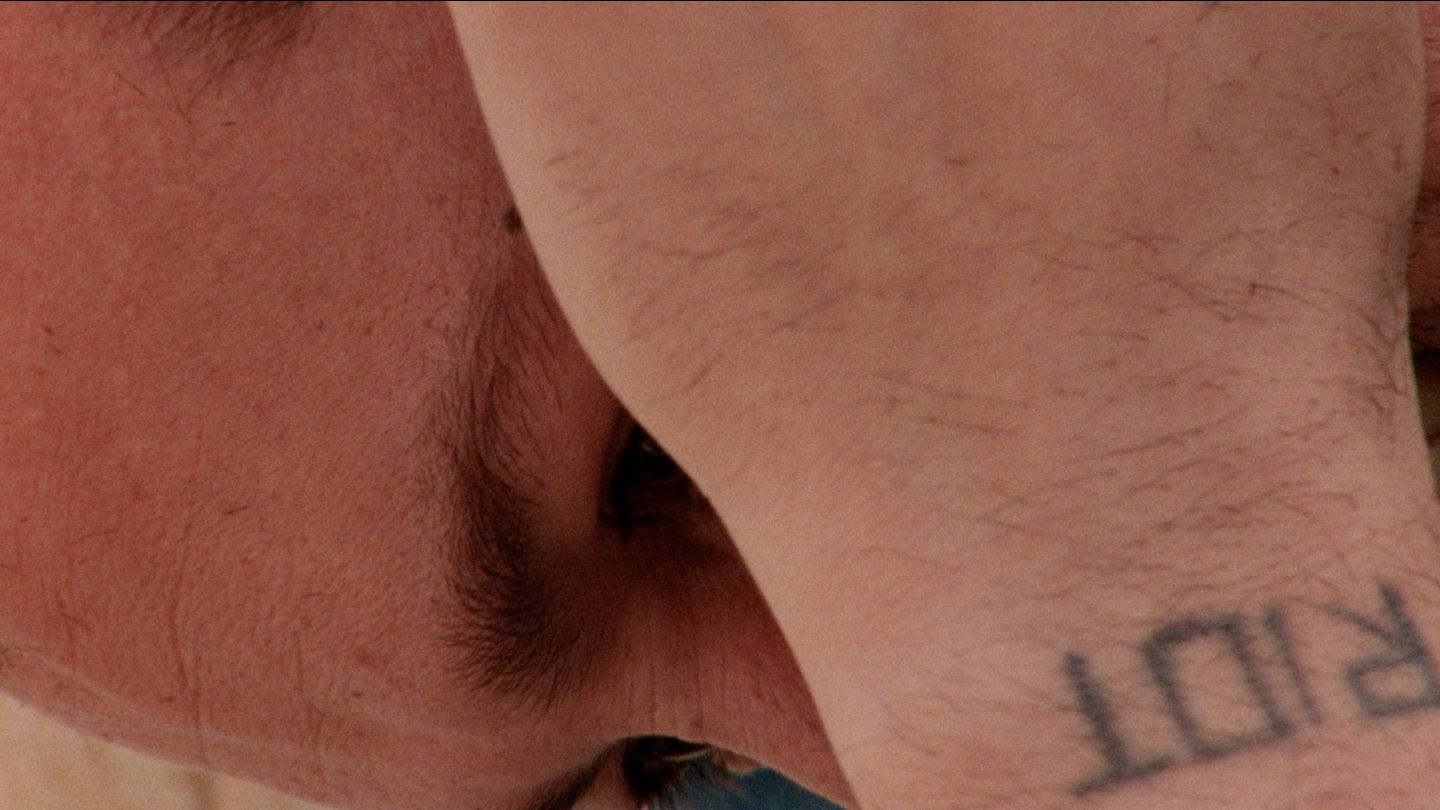

OUROBOROS (2017), BASMA ALSHARIF EXCERPT COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND GALERIE IMANE FARÈS, PARIS.

Basma Alsharif’s first feature film Ouroboros (2017) extends the discussion of the legacies of colonial violence on cities and communities. This experimental film follows a man through five different landscapes—the Gaza Strip in Occupied Palestine, Los Angeles and the Mojave Desert in California, Matera and Martina Franca in Italy, and Trohanet Château in Brittany, France—to mark a topographical meditation on the cycles of mass trauma and grief. Like the ancient symbol of the ouroboros, a serpent eating its tail, the film loops and upends itself in circles, existing outside of time and examining a desire for an eternal return to a place that is continually in the process of disappearing. For Alsharif, the atrocities committed against the Palestinian people and landscape are connected to other regions that are attacked in endless cycles of destruction and renewal. Among many things, Israel’s recent actions to forcibly remove Palestinian families from their homes in Sheikh Jarrah is an architectural and urbanism issue. There are discussions of Israelis creating new settlements, re-designing the architectural footprint of the neighborhood—this would change the entire demographic and social fabric of this area.

Within México City, when the Spanish colonized the Aztec Empire, they began draining Lake Texcoco to control flooding. México City is on the site where this natural lake basin once existed. Today, there is a dark irony that a city that floods in summer from heavy rain and is formerly a lake does not have water readily available. Instead, water has to travel hundreds of miles from wells surrounding the city through pipes and multiple purification plants and travel up over a 2,000 m elevation to reach the city. It is an impressive engineering feat that water comes out of the taps. Depending on class, different geographic areas have more volumes of water and more hours of running water per day than others. So every time you turn on a tap in México City, you are acutely reminded of the relationship between cities and their surroundings. After passing through a diversity of geographies—from the American South to Antarctica and the Philippines, the program ends in México City. Fernando Ocaña collaborated with composer Alejandro Veneno to create a portrait of México City. Junkspeed (2018) is a compilation of iPhone footage that Ocaña captured while driving through the city over several years and depicts the city’s character, speed, and movement and some of the people who inhabit it.