JOHN HOGAN ON DESIGN AND HIS INTUITIVE UNDERSTANDING OF LIGHT

Photography by Amanda Ringstad, David Clugston, Erich Ginder, and John Hogan

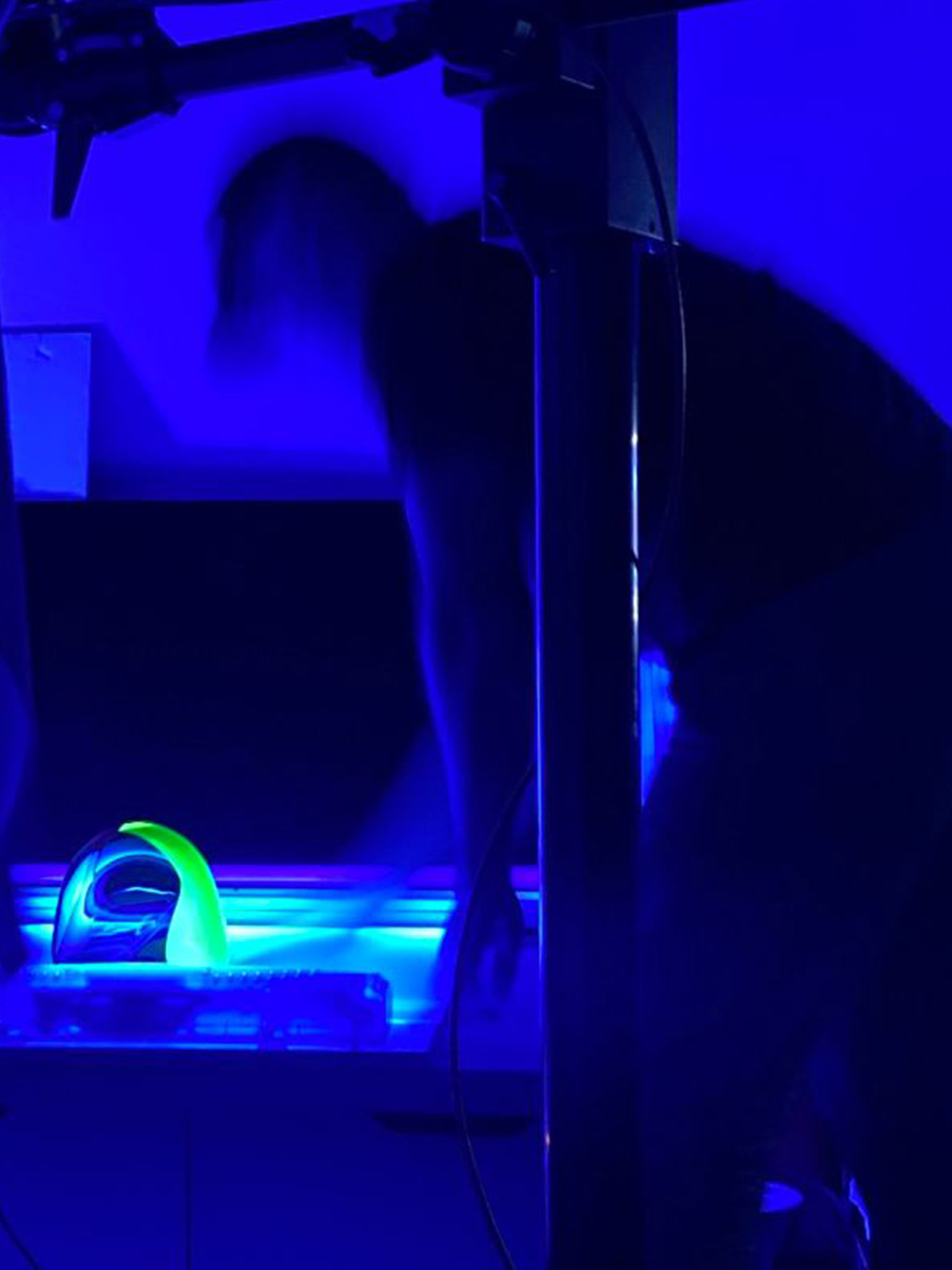

John Hogan is a sculptural glass artist with a new show, Ultraviolet, on exhibition now at The Future Perfect in San Francisco. Light is a proactive and integral component of Hogan’s sculptural practice. It’s not just an ephemeral, environmental condition into which his glass is placed, but an important part of the sculpture itself. John tells MATERIA about his muses, creative journey and what’s next for his evolving practice.

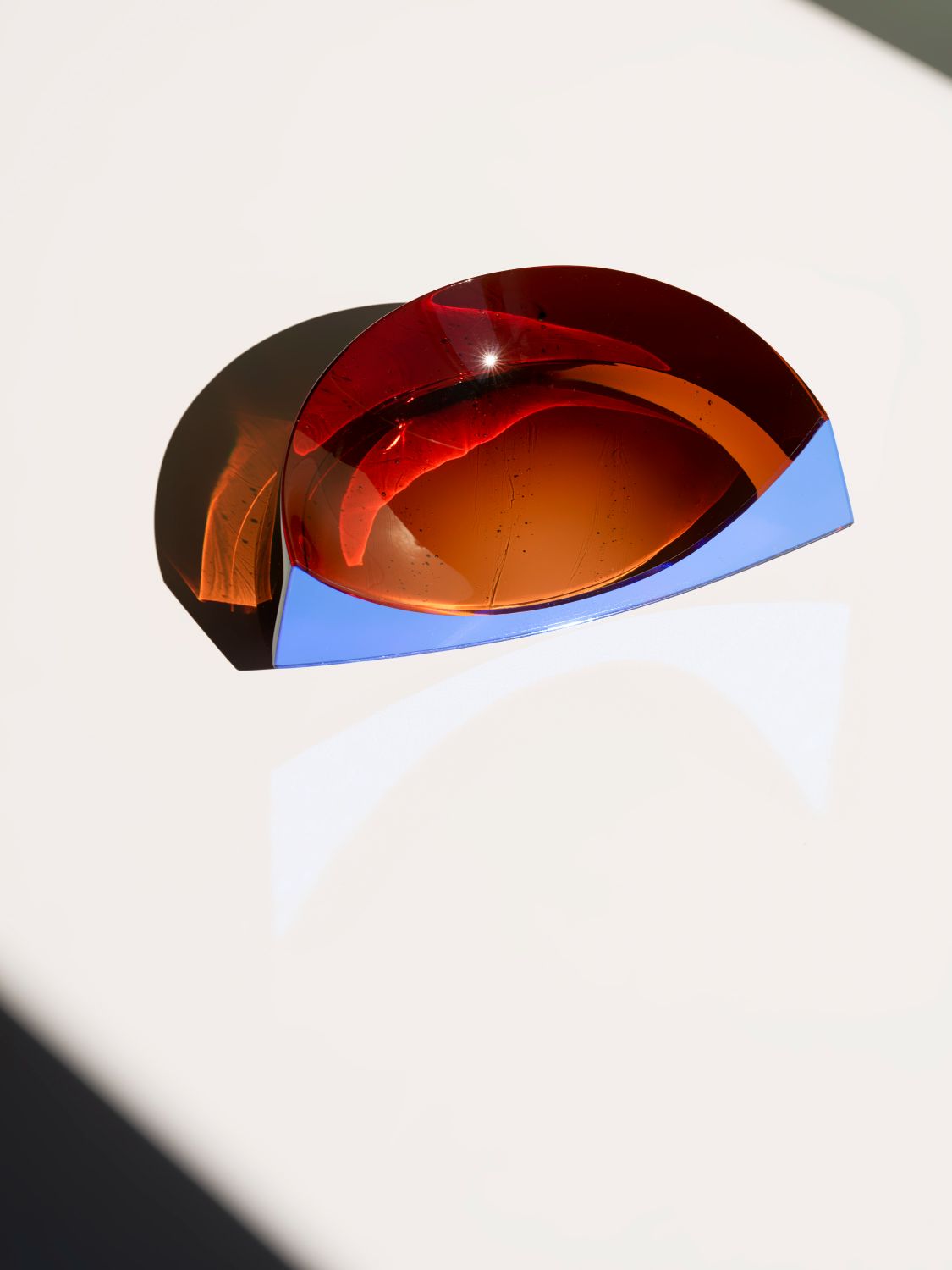

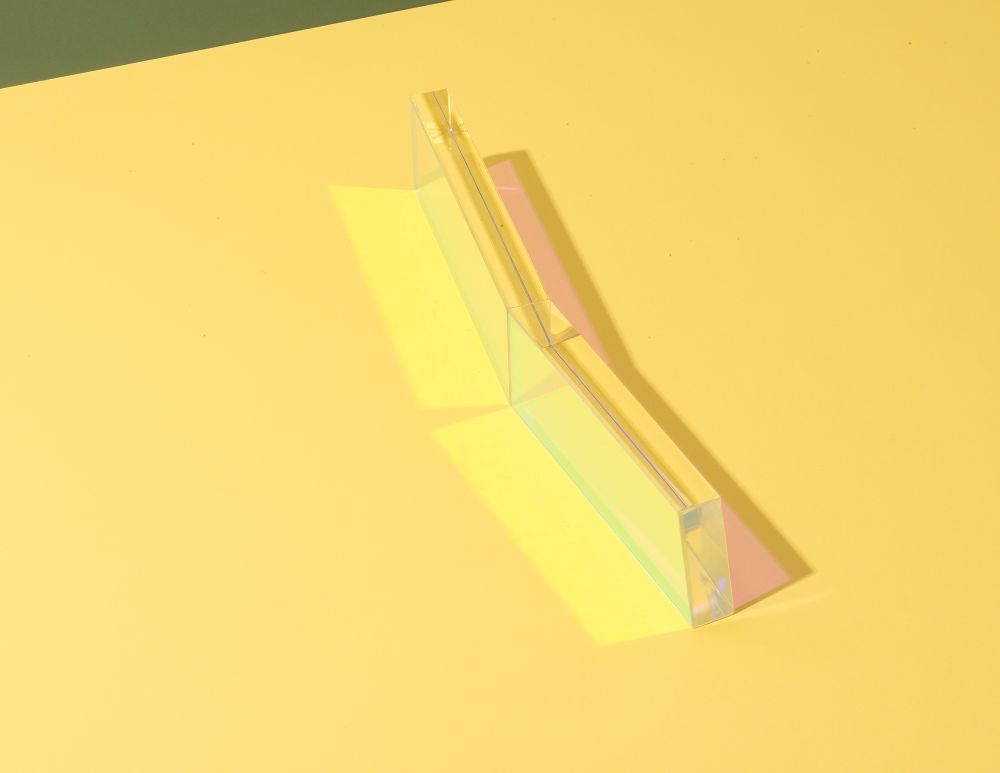

VEER, 2016. KILN CAST AND COLD WORKED GLASS. PHOTOGRAPHY BY AMANDA RINGSTAD.

MATERIA: Let’s start with your origin story. Where did you grow up? How did your journey into design begin and what influenced your evolution as a creative individual?

JOHN HOGAN: I grew up in Toledo, Ohio. I started making glass at the Toledo Museum of Art while in high school and made my way to Seattle to pursue a career in glass after I graduated from college. During the first years here in Seattle I was focused on building my skills and getting to a point where I could afford to have my own studio. In 2010 some of my friends and I started Studio 5416 where I developed my work for the first 5 years or so. Around 2014 I started meeting and collaborating with members of the local design community here including Ladies and Gentlemen Studio, Erich Ginder, lacoli and McAllister. My voice as a creative really took off when I stopped focusing as much on process and looked more to the material itself as well as outside interests such as music and culinary for inspiration.

MATERIA: Who have been your mentors or muses in the glass industry?

JH: Scott Darlington was my first real mentor in glass. He was the one that told me to look more at all of my other passions in life when approaching finding voice and inspiration for new work. Later, I worked in Milan Handl in Novy Bor to learn Czech style kiln casting and cold working. Osamu and Yumiko Noda really helped me to think about glass from a more fundamental perspective. The husband and wife collaborators Stanislav Llibensky and Jaroslava Brychtova are my all time heroes in glass.

MATERIA: You moved from one glass focused community in Toledo to another in Seattle, how does community and collaboration help your creative process?

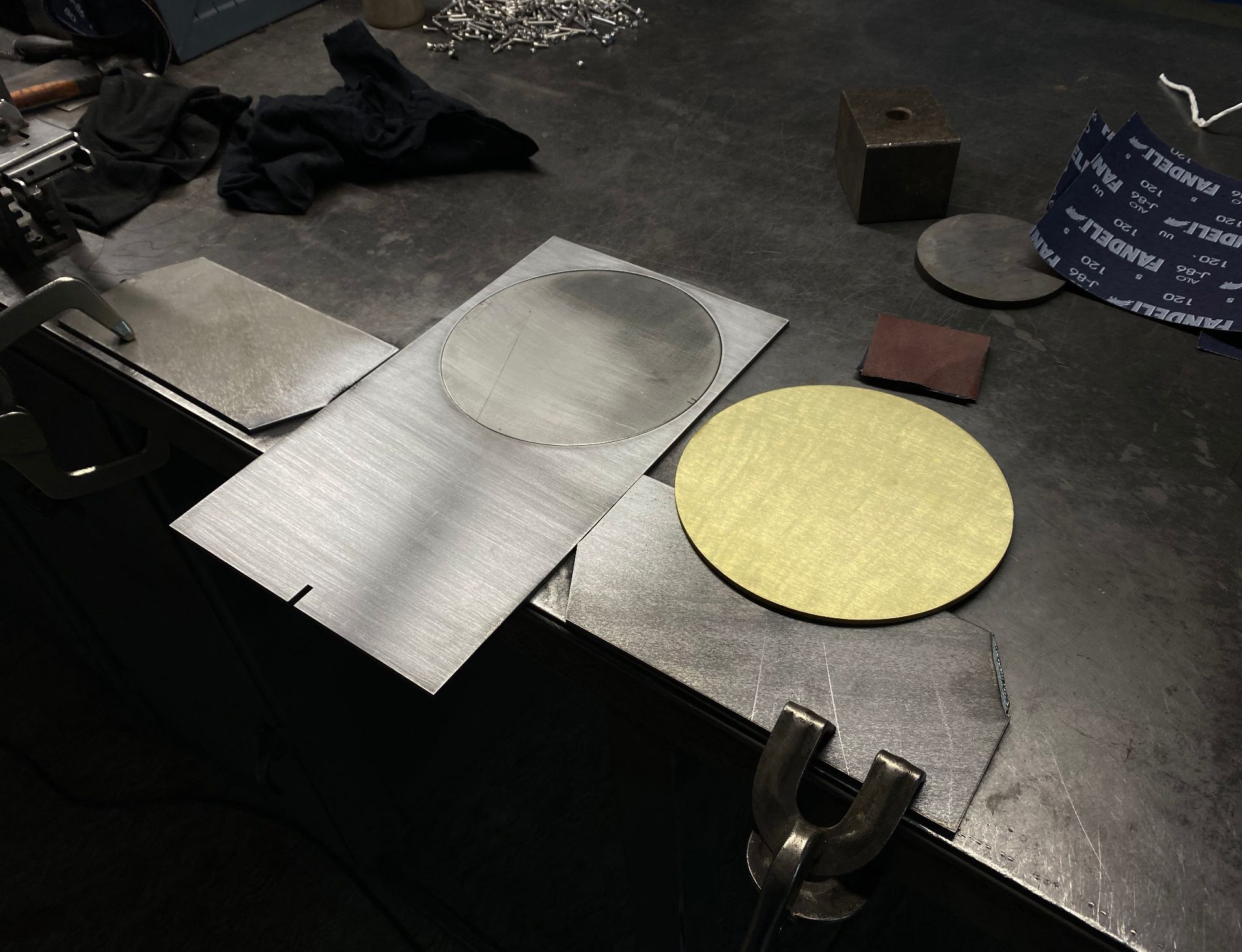

JH: Toledo is the birthplace of the studio glass movement. It is the place where artists first worked together with factory engineers to shrink down industrial glass technology to make art with a more experimental approach in the United States. When I was a child the movement was more than 30 years in, many studios had been started and an incredible community of artists was all around the area. That community worked with the Toledo Museum of Art to found their first hot glass studio where I was able to learn to work with glass at a young age. Seattle, because of its proximity to the Pilchuck Glass school has become the home to a community of progressive glassmakers since its inception in the early 70’s I continue to learn from and work with the community of specialists that are here in Seattle. Hot glass is always a collaborative, team focused process, but working in Seattle with specialists in cold working, kiln forming, and mold making allows me to push my design intentions beyond my own specializations.

MATERIA: What challenges exist in your creative practice?

JH: Glass is expensive to work with. It can sometimes be difficult without funded residencies and commissions to push experimental and new approaches or concepts. Menagerie is a newer body of work and a return for me to a miniature scale sculpture more like the scale I was working with when I first started my studio in Seattle. Working at a small scale is very freeing for me and allows me to push new approaches and aesthetics.

MATERIA: You discuss the relationship between object and light. Can you explain more about this dynamic and how it affects your work?

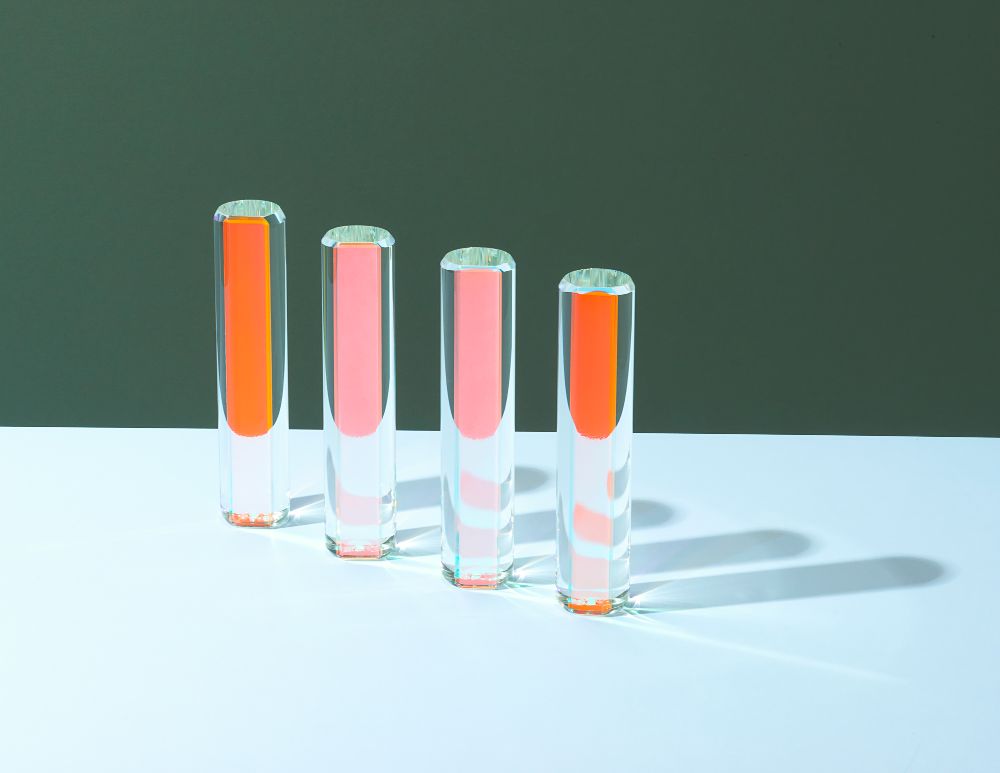

JH: In my work I am often creating sculptural lenses, sometimes with color, that concentrate and disperse light in unique ways. When working with glass the light doesn’t just make the object visible, but it actually changes because of the object. As I continue down the road of making work with glass, I constantly grow in my practical and intuitive understanding of light.

MATERIA: Is there a piece at the current show for The Future Perfect in San Francisco that stands out to you? What is special about it that goes beyond the eye?

JH: Concave with blue is a piece that combines the light focusing characteristics of a negative meniscus lens with color saturation shift possible with this type of crystal body and a graphic, contrasting slice of electric blue dichroic glass. The combination of dichroic glasses and colored crystal bodies is something I’m looking forward to exploring more in future work.

MATERIA: What are you currently working on that you are excited to share?

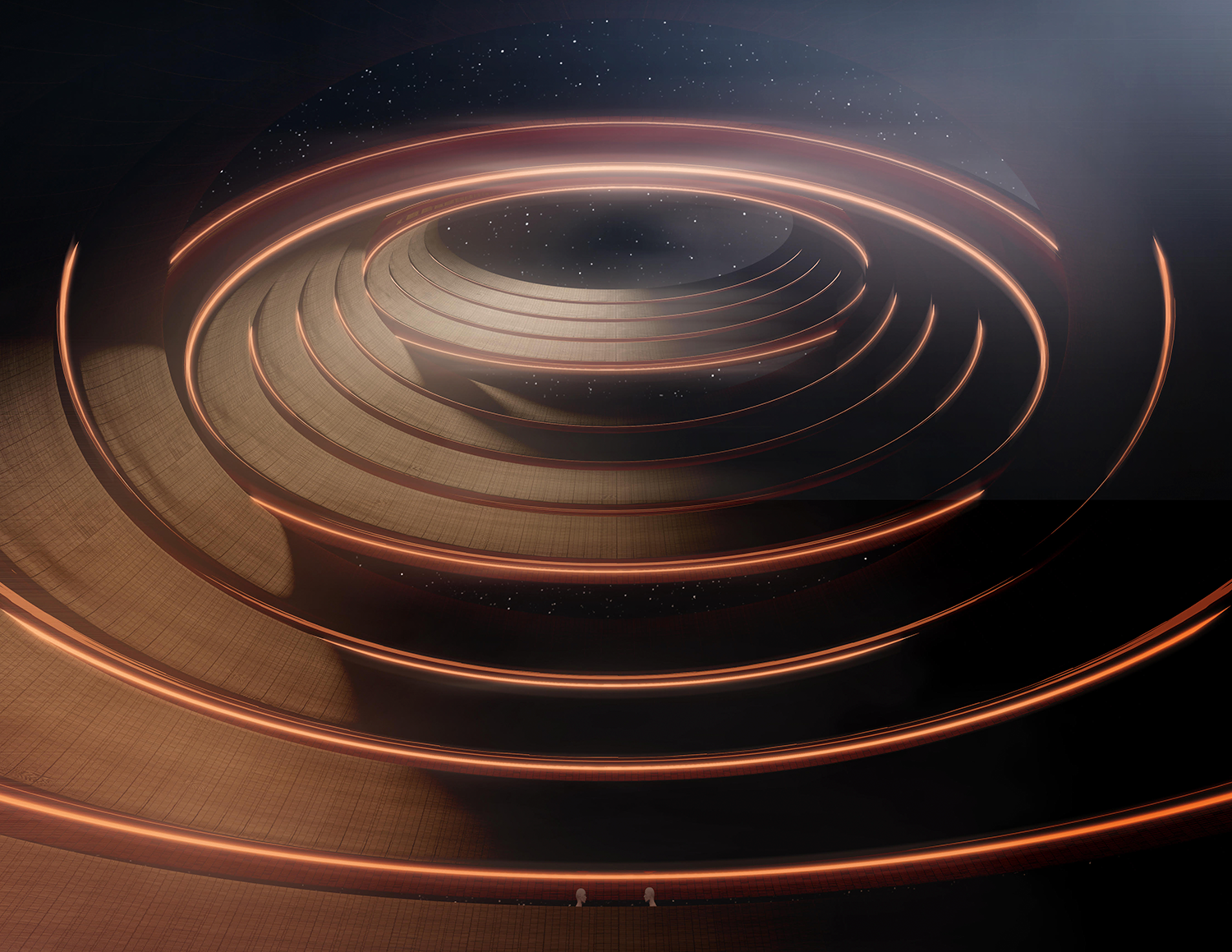

JH: I’m working with architect James Cheng, landscape architects PFS, and developer Ian Gillespie at Westbank on a project in Seattle called First Light. It’s my first project of this scale working with glass in a number of ways mixing architectural applications and sculpture throughout the building. The primary piece is a glass veil over the first six floors of the building, consisting of more than 16,000 optical lenses meant to resemble a piece of silk draped over the podium of the tower.

TIMBER, 2015. EXTRUDED AND COLD WORKED GLASS.