GLAMOROUS DECAY: A CONVERSATION WITH MAISIE COUSINS

Installation photography courtesy of Galería Hilario Galguera and Galería TJ Boulting

Jardín, cocina, basura, cuerpo on exhibition at Galería Hilario Galguera

November 3, 2021 to January 20, 2022

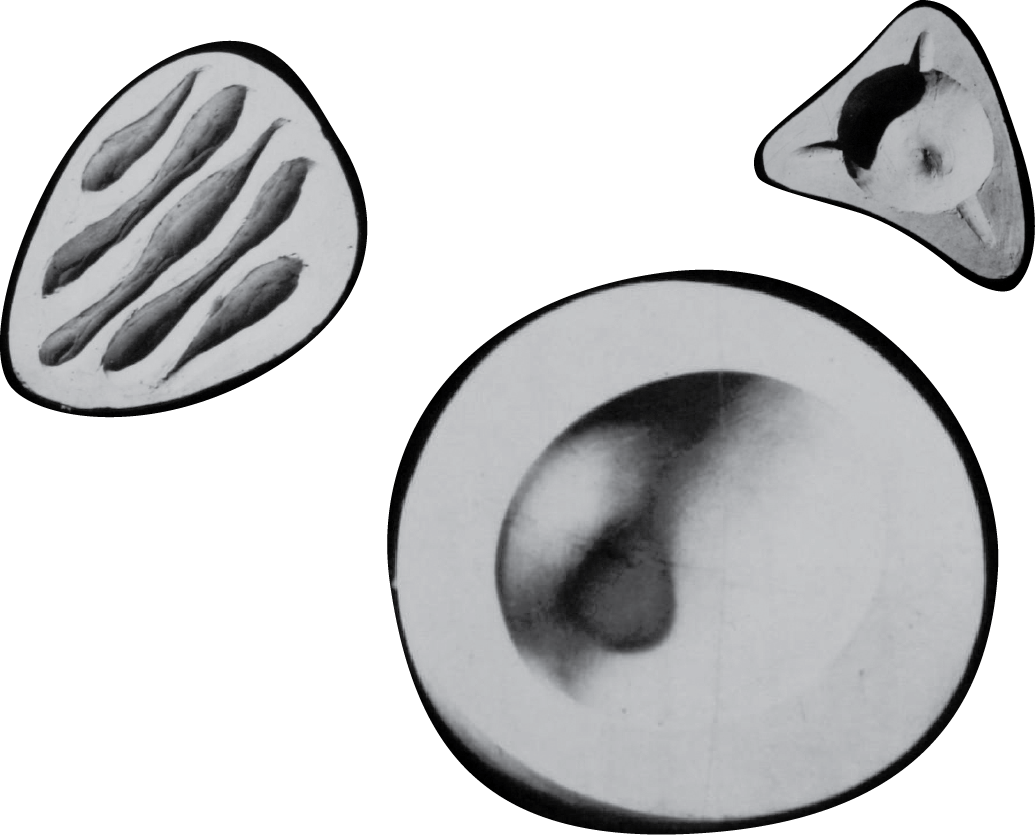

In her luscious large-scale photographic works, British artist Maisie Cousins embraces the mess and the chaos. Her images present us with elaborate micro-worlds that she constructs using organic materials in varying states of decomposition—incorporating insects, tropical fruits, and flowers. Balancing the fine line between the ripe and the rotten, her visceral and hyper-vivid images are a metaphor for carnal desire, gluttony and over-consumption.

Aleph Molinari met with Maisie Cousins at the opening of her latest exhibition “Jardín, cocina, basura, cuerpo” at Galería Hilario Galguera in México City to discuss the origins and inspiration of her work.

ALEPH MOLINARI: You were born in Somerset and grew up in London. Do you think that the obsession with color in your work is an antidote to certain aspects of your Englishness?

MAISIE COUSINS: Definitely. The UK is so sterile. It always shocks me when I come back from México or elsewhere. You get to Heathrow and everything is just grey. There is a false security in the sterile-ness, like the way everyone is obsessed with the anti-bacterial stuff. Germs are good. You need a certain amount of germs to build up your immunity. I feel the same way about the UK. It’s like hush hush, trying to hide the nastiness, which everybody has.

AM: So color is a way of liberating yourself from this greyness?

MC: I think so. The colors and the garishness are a reaction to learning fine art photography and theory that verged on philosophy, over-thinking and over-conceptualizing images that I didn’t even find that interesting. It could be just a black and white image of a tree in the distance, and there’s a fucking essay to accompany it. I just wanted to scream when I was learning about stuff like that. It was pretentious to me. And fucking hell, a lot of the work was so technical and clinical. That is why I have a love-hate relation with photography. I hate how technical it is and how you have to look after your equipment. For me, it’s about the thrill I get from dangerously dangling a camera over water or a bin of rubbish. And it’s ironic, because now I can’t not use a camera. It’s like another arm. Anything I see, I see as a picture.

AM: So your work is a way of screaming?

MC: Yes. The reason I love making art is to be in my own world. To be by myself. As soon as I left university, I thought, “I don’t care about making it, or becoming an artist.” I just wanted to make work that genuinely excited me, and not have to prove it to anybody or be graded on it. I didn’t want to come up with a theory and then make lackluster work. It needed to come together organically rather than thinking about it.

AM: And where did the fascination with the visceral originate? Is it something from your childhood, or from memories?

MC: It’s two things really. One is an interest in trash, in the rubbish. I definitely got that from my granddad. He used to take me often to the dump with a metal detector. That was our thing. He thought he would come across something of value—a treasure—and we would become rich. Finding things like Barbies in a big heap of rubbish was like, “Oh my god, this is special.” And also, I’ve always picked my nose. Maybe it’s a bit gross for some, but I don’t think it’s gross. It’s scary that people don’t know what’s going on inside their bodies.

AM: So it began with your bodily fluids and secretions?

MC: I suppose. When I was in my early twenties, it was still seen as radical to have armpit hair. Obviously times have changed to some extent. My Mum is a big feminist—she’s punk—and I wasn’t raised to think anything was gross. When you get older you feel the pressure to be groomed and be polite and not fart and stuff like that. Fuck it! We are too suppressed. Everything is too suppressed, especially in the UK.

AM: Do you feel that the textures in your work – the liquidity, the wetness, the vividness—are a fetish?

MC: I am not really into the word fetish. I’m sure to some extent there is a sexual attraction to those sorts of things, but for me that’s honesty and nature. It’s funny you talk about sexuality, because I’m coming out of a stage where I was hyper-focused on sex and pleasure. After having a baby I’m coming out from the other end thinking that I don’t need to sleep with more men. I’ve done that and that got me my gorgeous baby. I loved every minute of being pregnant and giving birth, but I was not prepared for the sacrifice of not being able to do my work. I see the love for my child the same as the love for my work. I see this predicament now and I’m trying to learn to have a balance and it’s more interesting to me than feelings of horniness or wanting to have sex.

AM: So there was a more sexual aspect to work before?

MC: Absolutely. It was all I ever thought about. Now I’m interested more in the actual body rather than images that could represent the body. I feel like using the body more in my work. Although I don’t like taking pictures of people anymore because I feel the balance is immediately off and the photographer has too much power. Really, I should just do it with my own body, but then there are technical aspects and I hate tripods.

AM: In some of your work the body almost resembles food. It looks as if you are basting meat, the way it’s being held like a plucked fowl. How do you want to approach the body in this upcoming phase?

MC: Absolutely. It’s about always trying to push it. Sometimes I take pictures and I’m like, “This is gross and it’s actually starting to smell.” But I keep doing it for a little bit more, pushing the boundaries of what I’m comfortable with. The reason why I want to go into the body because my work is not a test to me anymore, it’s not scaring me enough. I’ve always been attracted to zoom. I want to get inside the body and have a look. With a camera, with those little cameras that go inside the body. I like dentist pictures, so maybe through the mouth. Pipilotti Rist, one of my favorite artists, has a video where a camera goes in the bum and comes out the mouth, over and over again. It’s funny— eat, shit, repeat, all day.

AM: Well that’s a function of photography, to provide a new way of viewing. So what scares you?

MC: I’ll tell you what is fucking scary: pushing a nine-pound baby out of your body with no pain relief. I wanted to know what it felt like, how painful it was, and what would come out. That’s why giving birth was the best. The placenta was a stepping-stone. I still can’t believe it came out of me.

AM: Is there a critique on food wastage and consumption in your work?

MC: Kind of, but also a bit of a knock to it. It’s half-half. What I find gross, the thing that makes me go, “Ohhh we are awful, we deserve to be extinct,” is going on Instagram and seeing constant indulgences— endless expensive food and going out to restaurants. People are shouting at the top of their lungs: “I’ve got gout.” For me, it’s too much of a performance. We’ve come to this chaotic point where there is too much food and too many options. We are too spoiled. It makes me laugh seeing all these dinners with steak and rich food, because I just think of the kind of poo that will come out.

AM: It’s a question of consumption as a way of having power in society. Social media puts people in that frame of mind, of wanting to participate in a perfect lifestyle where everything is a feast of some sort.

MC: Yes, and it’s cringey. All aspirational. Everything is going in, in, in. We are always obsessed with things going in. Dicks, in. Food, in. We never really talk about what comes out. It’s rude.

AM: Maybe we should do a Shitstagram.

MC: Totally. I’ve always thought about that.

AM: Do you also photograph poo?

MC: No, it’s not too aesthetically pleasing. If it was colorful, maybe.

“I like the middle ground between something that is enjoyable and beautiful but also really disgusting. I love the aesthetic of 1970s food.”

— MAISIE COUSINS

MC: I like the middle ground between something that is enjoyable and beautiful but also really disgusting. I love the aesthetic of 1970s food. I like that grey area of, “Oh I don’t know, but I want to keep looking.” It’s like picking a scab. Even though you’re not supposed to, you do it anyway because it feels good.

AM: Is your vision of beauty linked to the grotesque?

MC: I guess so, because it’s honest. It’s real, it’s not embarrassed, and it’s not hiding anything. I don’t like things and people that are proud. I like the foul, the dirty, the real. I like to embrace the mess and the chaos of it. Also, just doing the things that we are told we are not supposed to do, like leave a mess out. I like the idea of things that get left behind, the lives they take on. Think of the bins in restaurants at the end of the night, after people have taken their pictures with their food and probably ate only half of it. What happens to all of that? That’s all going to react together in scrap heaps. There must be life in all that rubbish. I’m interested in discovering what’s going on in these micro worlds.

AM: I feel that your work is going to be read differently in México. México has more contact with the grotesque, the surreal, the visceral…and with death. You go to any market or bus stop and you see tripes and organs being boiled or fried; at the butchery there are heads and corpses hanging, and in the streets they sell insects.

MC: Yes. In México there’s a sense that people are not embarrassed, they’re unashamed. And the advertising is way more beautiful here. There are murals in the shops and the signs are hand painted. It’s everyday art, which is so different from Europe where everything is made of metal and plastic, made to look clean and sterile. When I went to Cuba several years ago something went off in my head. It was an epiphany. I was twenty-five and had never been outside of Europe. Cuba felt so human, so sexy, so fun, so exciting. Unashamedly chaotic, in the best way. It was a complete eye-opening experience. I wanted to keep living this high when I went back to London, to keep living in this beauty and chaos.

AM: Did you ever think of adding smell to your exhibitions?

MC: I did once, yeah. It was for my fist solo show in London. A perfumer called Azzi Glasser, made a series of smells based on her first reactions upon seeing my work. One was the smell of rain on concrete, another was a sickly sweet violet smell, and the third one was cut grass. We went with the sickly sweet one, since decomposing [organic matter] often smells sickly sweet, like decomposing fruit.

AM: Tell me about the title of this exhibition.

MC: I don’t like to think too much about titles. Basically, I approach pictures like a shopping list. I want rubbish here and some dipping sauce there. I go out and take out my list and put it all together. So, it felt like the title of the exhibition and the book should be a list. It’s ‘Garden, Kitchen, Rubbish, Body,’ because each room has something going on. It ends up at the body. It’s the circle of life.