LOUIS DUROT: ON THE SCIENCE OF ARTISTIC CREATION

A Materia Studio Production

Find the Holy Chair from Louis Durot in our Materia Shop.

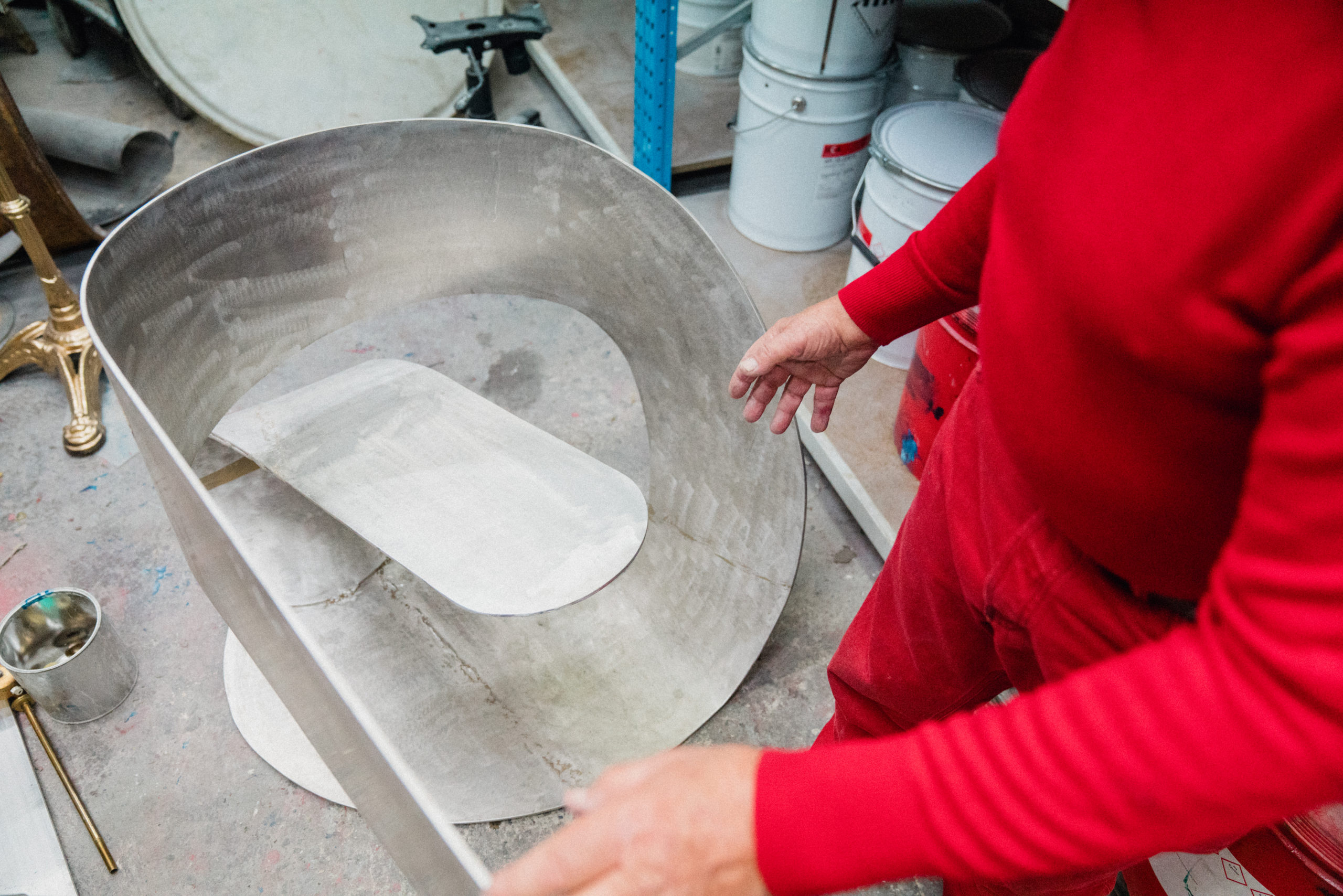

Materia sits down with seminal French Pop Artist, Louis Durot, to discuss his storied life and career spanning six decades. From his early life marred by war, to the youthful artistic rebellion of the 60s, to his prolific career as an artist, scientist, and inventor – Louis Durot is a living icon of the pop art scene. We visited him in his Parisian studio and factory where we were able to document a catalog of unseen work, witness firsthand his process of polymer fabrication, and even hear anecdotes of run-ins with Picasso.

Prashant Ashoka: Can you describe your childhood and the impact it had on your life as an artist?

Louis Durot: My childhood started with a miracle. My mother was Jewish and our family was fated to end in a gas chamber. During the war my family was put on a big truck with many others to be transported to a railway station where we were meant to get on a cattle train to be killed. However, as the truck was en route to the train station, it was stalled by an attack from underground fighters. I was extremely young, but I vividly remember reaching the train station, and the cattle train had already started to leave, just as we arrived. We missed that one-way train by minutes. It was Christmas eve. The Nazis, who wanted to go back to their own families, decided that we were all to be brought back home and rounded back up after the new year to be sent to the gas chamber. When we were taken back to our small village home, I remember returning to an empty house. Everything has been stolen. We decided to flee and I was separated from my parents and sent away to hide in a small village in France. I was so young that I did not know my own name. This was also not taught to be for my own protection, and many Jewish children at the time in hiding were given new names to protect their identity. I lived in hiding with about 40 other little kids, and I believed I didn’t have parents anymore because I never had news of them. This was the beginning of my life.

‘So during the day I would go to this river and use the clay to make toys. For myself and also the other children. I made clay toys of elephants, boats, and soldiers. I started this in 1944. And I am still doing it now.’

– LOUIS DUROT

Of course in this time, none of the children could get anything that you could call a toy. However, in this village where I was hiding there was a river. And on certain spots on the banks of this river I would find clay. Clay of different colors. There was green clay at one spot, red clay at another, and gray clay. So during the day I would go to this river and use the clay to make toys. For myself and also the other children. I made clay toys of elephants, boats, and soldiers. I started this in 1944. And I am still doing it now.

PA: Would you describe your youth as rebellious? Did this contribute to your shift into an education within engineering?

LD: In my youth, I had to fight for my survival. In the village where I was hiding, we were kept in a barn with the goats and other livestock. I was very young and malnourished. And everything was a matter of strength. We had very little food, and as I was smaller than some of the other children I always got the last scraps. But when you are starving you have to fight to survive. When I grew up and started to go to school, I became unable to suffer discipline or take orders from anybody. And this is why I could never be employed. I have only been employed for six weeks in my life!

I am world known as a polymer scientist, and I work to produce new polymer molecules which are what you call plastics. But throughout my career I have worked freelance as a consultant engineer. And the people I work for have to accept my rules. I cannot work in an office or lab for extended periods, my time is always free for my own experimentation, and I am not pressured to produce reports.

PA: Would you say that furniture is the primary expression for your art, and why?

LD: Furniture is my subject. A good example is my spiral chair, which has become an iconic piece of my work. When my work is exhibited in galleries, it is often placed on a pedestal. And the audience interprets it as abstract sculpture, when it is in fact furniture. This is part of my game. To produce these toys that can be interpreted on different levels.

PA: What ideas inspire your work?

LD: I am inspired by otherworldly shapes. I want to create totally new and innovative shapes that have never been designed or thought about by anyone else before. And I also want to create these shapes using materials that have never been made before. This is how engineering and my art meet. I am inspired by the ability to create something totally new.

PA: In 1964, you founded the Freelane Studio. Could you tell us how this was born?

LD: In 1964 I was young and had little experience with the art world. I remember going to see gallery managers and presenting some drawings of my works, but I was always shown the door. At that time no one wanted to hear about such work – plastic was not seen as a valuable material in art. It was viewed as a material only for consumers, meant to be discarded. Materials that were considered valuable at the time were marble and bronze. Or antique furniture carved from wood. Pop art was not accepted. Even at the time Andy Warhol would not be accepted in any reputable galleries.

So the Freeland Studio was based on the principle of gathering artists who were refused by the art world elites. We had artists in jazz, design, theater. It was a collective for expression and freedom in art.

The 1960s was a joyful period. People were connecting and creating art, without the goal of selling. When you needed work, you just checked for jobs in the classified section of the newspapers and work was always available. It was an easier time because it was not difficult to be an artist. And the object of art was not the sale of art.

PA: Technology and research has played a large part in your career as an artist. Which of your patents or discoveries are you most proud of?

LD: Technology and the development of new materials is intertwined with my work as an artist. As a polymer scientist I have developed and tested many formulas to create new polymer molecules. Multinational companies hire me as an independent researcher to develop these materials and patents for them. Of all my patented formulas, the most profitable has been liquid waterproofing.

‘Technology and the development of new materials is intertwined with my work as an artist.’

– LOUIS DUROT

I used to produce these formulas independently under my own company DURGALITH which was then bought by a larger company who wanted to buy my technology as well as hire me as a research consultant to continue improving the technology.

My work in technology and research also came with a cost. It was the cost of time. In a sense I gave up 14 years of my career as an artist, from 1970 – 1984 to focus on the creation of new polymer materials. And at the end of that period I was convinced that I had reached a point of success in my formulas and started to produce art again.

PA: What draws you to spiral and organic forms in your work?

LD: I work as both an industrial engineer as well as an artist. In the engineering industry you have to follow very strict rules of geometry. The reason for this is because it is easier and cheaper for machines to produce geometric shapes as opposed to organic shapes. My use of organic forms in my work is really a rebellion against the clean lines of the industrial aesthetic.

‘Making furniture that is functional means that I have mastered the material which I am using and have made an object that has a purpose.’

– LOUIS DUROT

PA: With the Pop art aesthetic, shapes suggest something other than their function. But how much does functionality inform the making of your furniture pieces?

LD: Functionality is the pretext for my art. Making furniture that is functional means that I have mastered the material which I am using and have made an object that has a purpose. Within these parameters I explore the abstraction of objects, to create art that provokes thought and curiosity.