Based in Paris, Grace Atkinson collaborates with artisans to create textiles using weaving techniques from the Carpathian Mountains dating back to the 14th century. Her large-scale textile works take many forms: rugs and bed covers, furniture pieces, massive cushions, or artworks to hang on the wall. Inspired by the colors and textures of the landscapes of her native New Zealand, she sees textiles as powerful reflections of culture. Her sketches combine poetry and geometric patterns, which she then translates into textiles full of texture and electric vibrancy. Aleph Molinari, editor-at-large of Materia Magazine, met Grace in her Paris apartment, filled with books, design objects, lamps, and textiles. Over tea, they discussed the importance of texture in a world flattened by screens and the digital.

Aleph Molinari: Tell me about the place where you come from in New Zealand.

Grace Atkinson: It’s a picturesque port and surf town called Timaru. Although growing up there felt incredibly isolated, it’s very rural and surrounded by farms. I grew up between there and another town in the central South Island, Wānaka. This town has an intense feeling because you’re surrounded by mountains and have an open view onto a vast lake. It’s a very special place.

AM: Was this landscape a big influence for you?

GA: Even though I’ve been away from New Zealand for a long time, I feel that my identity is tied to the landscape; it’s part of who I am. I’ve always been drawn to nature and extreme landscapes, and experiencing their intense colors and textures sharpens the eye. I feel incomplete if I don’t get a dose of that kind of nature every now and then.

AM: And there must be a big culture of wool and wool-working there, right?

GA: Yes, naturally, with all the sheep. In the town where I grew up, there was a factory for making special bush and hunting gear called Swanndri. These pieces have a rawness to them: very tightly woven wool, not very soft but extremely warm and waterproof, often in tartan. The factory would sell off-cuts that I would buy for my sewing class at school.

AM: Is that when you started being interested in textiles?

GA: Textiles have always been an intrinsic part of my surroundings. My mother had a big collection of beautiful antique pieces. She used to have a vintage store before I was born, in the early to mid-eighties. It was probably one of the first vintage stores in New Zealand; it specialized in clothes from before 1910, so really crazy pieces. She had rare textiles at home from her travels to India and Afghanistan. And my father had been a carpet layer before opening a flooring shop, so I was surrounded by carpets. It took me a while to realize that I had come full circle.

AM: And when did you start creating textiles for yourself?

GA: I started sewing from a very young age; I was really interested in making clothes. I began a career in fashion after high school, doing styling and consulting. I pursued that for some years, but it wasn’t the right fit for me. I was trying out different things—taking photos, working in galleries, producing quilts for an artist friend. But I knew I wanted to start my own project working with textiles. This led me to artisans in Ukraine producing wool pieces known as lizhnyk, a technique developed in the 14th century by the Hutsuls in the Carpathian Mountains. They are woven on a wooden loom, then washed in the river, which slightly felts the fibers, left to dry in the sun, and finally brushed by hand on one side, giving them a furry, textured surface.

AM: Do you only work with these artisans or in other places as well?

GA: I work with artisans in Portugal who weave and felt wool pieces that also have a furry nap but are lighter, and in Spain with mohair. Many of these techniques are dying out, so it’s a privilege to be able to work with these artisans.

AM: Do you think that we have the capacity to revive ancestral weaving techniques that have been forgotten or lost?

GA: I think it’s important to acknowledge that many ancestral weaving techniques were disrupted or lost through colonialism and the imposition of capitalist systems on Indigenous communities. The capacity to bring them back exists, and there are artists and organizations working to preserve and revive these practices. Yet recovering these techniques is more about listening to those who carry this knowledge and supporting its continuation on their terms. Textiles are powerful indicators of culture.

AM: You seem to have grown up surrounded by many forms of textiles, from carpets and rugs to sweaters and blankets. What does a textile mean to you? How would you define it?

GA: The essence of a textile lies in the idea of things being woven together, both literally and metaphorically. At school we learned a traditional Māori weaving technique, beginning with harvesting flax. The flax is symbolic, with the center representing the child, surrounded by the parents and then the wider family. Only the outer layers are taken to protect the health of the plant. This felt especially meaningful, as it connected the physical and the metaphorical. Your question also makes me think about the nature I grew up with. Everything felt like a collage. I was constantly collecting things from my environment: stones, leaves, insects. There’s something about this accumulation of natural textures that feels like a textile in itself.

AM: Textiles are also ways for cultures to weave their narratives and stories. Do you feel like you’re weaving your own story through your works?

GA: Absolutely. There are definitely parts of my own story reflected in my work. The pieces I make from old garments and antique fabrics are mostly improvised and often become particularly personal. One of these works was constructed using fragments of my great-grandmother’s fur coat, a silk scarf from my teenage years, and a hand-knit jumper I bought in New Zealand during an intense period just after my father died. The memory of that time, and its connection to the materials, is embedded in the piece. There’s also an interesting convergence of stories in my collaborations with artisans. Although I don’t have a direct cultural connection, I’m deeply engaged with their craft and with the process of exploring new motifs and forms within that context.

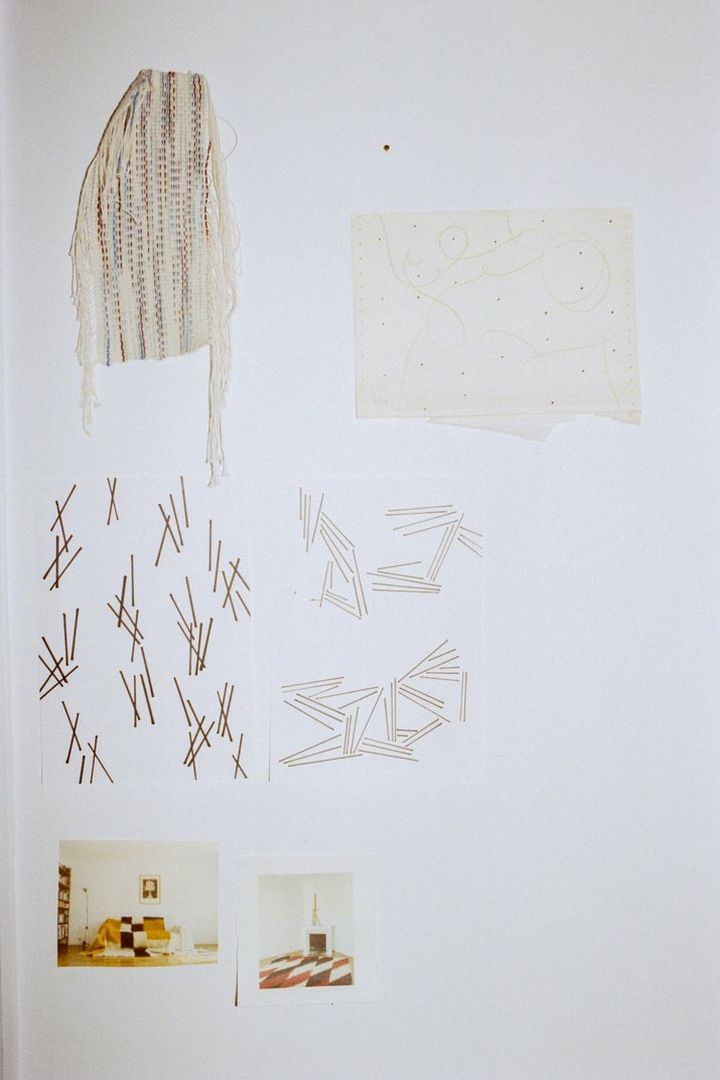

AM: How do you transfer your drawings and geometric patterns onto the textiles?

GA: When I started I needed time to understand how the pieces responded to the constraints of the technique. The direction the textiles are brushed changes the intensity of the lines, making them softer or more rigid. Over time I have built an archive of motifs that I’m developing through disruption and distortion, which is especially interesting as every piece is unique. Even when a motif recurs, variations in color, texture, and rhythm emerge through the hand weaving. Part of this process is about translating and communicating motifs to the artisans and seeing how the pieces evolve through interpretation.

AM: Your pieces can be a bed cover, a carpet, an art piece on a wall, a piece of furniture, a cushion. Are all of these forms and formats interchangeable for you?

GA: Completely. I prefer to focus on exploring the motifs and forms than thinking about how an audience might perceive my pieces. I love the openness of knowing they can be conceived in different ways. The pieces also evolve throughout the production process; the colors can turn out differently than I expected, and there are steps where the artisans interpret things in their own ways. There’s been a huge shift in how craft is seen and the level of respect it is given today. My work oscillates between design and art, so it’s often the setting that contextualizes it.

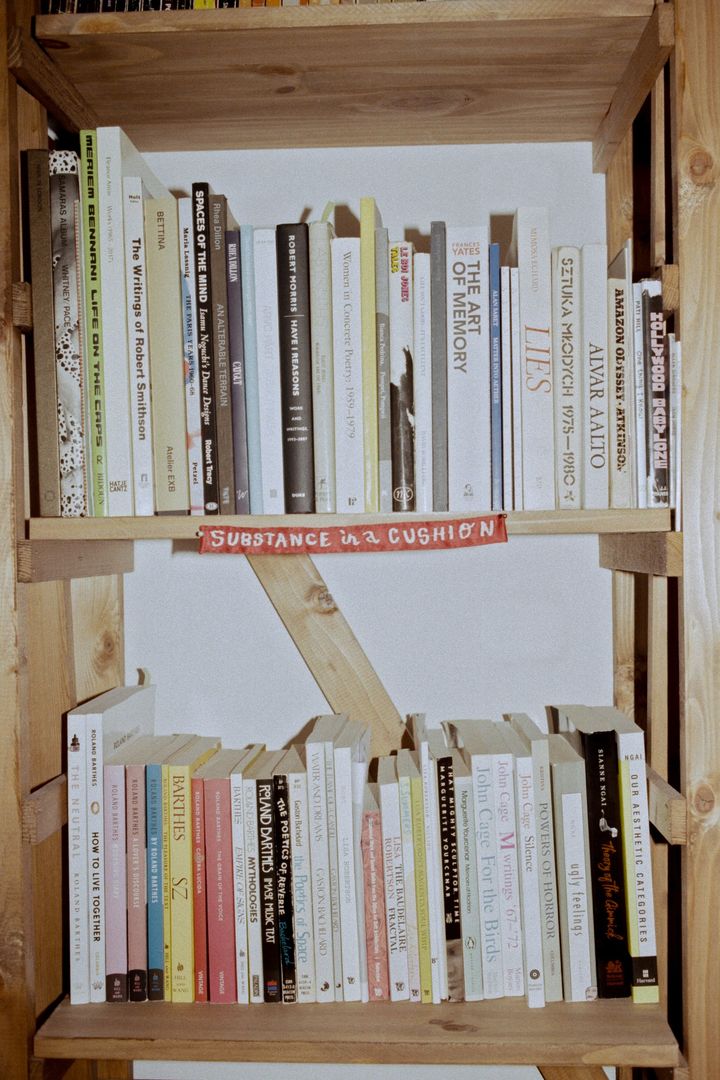

AM: Text and textile share the same root, and you work closely with literature, even designing from poems. How does literature influence your creative practice?

GA: For me, the process of designing becomes more fulfilling when I can go deeper with research or through reading. Sometimes there’s a direct link through titles and poetry, but even when no apparent connection exists, it still informs the process by helping me feel aligned with the design. It’s experiential for me, and reading connects me to the world around me.

AM: In a world where we experience much through screens, do you see your textiles as a way to reconnect with the body?

GA: Social media and the way things are shared on the internet have democratized access, but the oversaturation of images flattens objects and artworks. When someone is interested in a piece, I encourage them to see it in person so they can truly understand its characteristics and texture. I’m interested in how textiles create an emotional texture in a space and how they can offer comfort through softness or weight. I’m an extremely tactile person, and I find comfort in how textiles can subdue the senses by modulating sound and absorbing light.

AM: Yes, and textiles are a reminder that we still have tendrils. Bodily comfort is anti-digital.

GA: Yes, I often feel disconnected from my body or too much in my head. Working with these textiles is a direct way for me to reconnect with my body, which feels essential today.