GETTING INTENTIONAL WITH BRIAN THOREEN

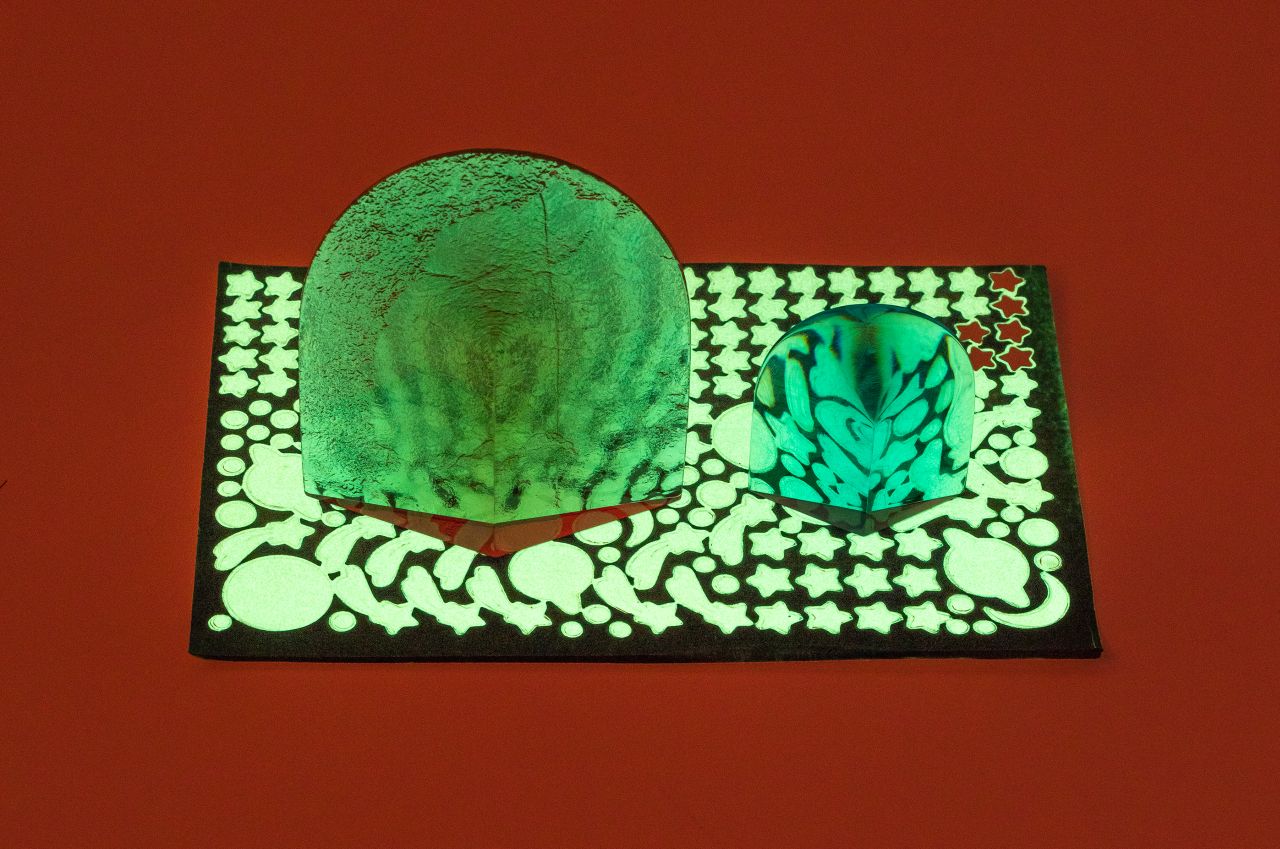

MATERIA visited México City-based designer and artist, Brian Thoreen in his light-filled live work studio in San Miguel Chapultepec. The designer is involved in some of México’s most important curatorial projects such as nomadic gallery MASA and VISSIO. As a designer he pushes the boundaries of whatever limits are intrinsic to the materials he works with—whether hand-blown glass, industrial rubber sheets, wax or hand-hammered copper.

The LA contemporary art scene is where he found his early mentors. Thoreen talks about slinging mud across the studio with Richard Long, wearing many hats including studio assistant to Tony Delap, working with Enrique Martinez Celaya and as an installer for James Turrell.

Thoreen talks to Sarah Len, MATERIA’s Editor-in-Chief about his ambitions for the future, one of the greatest myths of the art world and intention above all else.

SARAH LEN: Let’s start with your origin story.

BRIAN THOREEN: I was born in Newport Beach and grew up in Costa Mesa, Southern California. My father was a contractor. My mom had a sewing factory. I grew up working with my hands, working in construction and learning to sew with my mom. She used to make a lot of our clothes.

I was always interested in building and fabrication. I got into welding when I was in high school. Later in community college my painting teacher took me under his wing working as an art installer with him on the side. Later I was the studio assistant for Tony Delap in Laguna Beach. He was a big figure in the modernist abstract scene in the 60s and 70s.

After that, I moved to LA and started as the installer at Griffin, which is now Kayne Griffin. Through Griffin I got to work with a ton of amazing people such as Enrique Martinez Celaya, Peter Wegner and Richard Long.

After a while, I left the art world because I wanted to get into design and architecture. I got a job as a carpenter at Marmol Radziner, an architecture firm in Southern California. That’s where I found one of my mentors. He taught me everything about metal fabrication.

And then when I was 31, a friend and I started our first design business together. We did restaurants, homes, interiors and custom furniture. We split up around 2014 and I went on my own putting all my focus into furniture. I first showed my pieces with Sight Unseen In the Collective Design Fair in 2015— it took off from there.

‘Intention is something I think about a lot. It relates to your previous question, to function and nonfunction. I think the piece depends on the artist or designer’s intention. Intention is focus, specificity, knowledge and thoughtfulness. I like to think, I like to ponder, I like to let things percolate in my brain for months before I ever do anything about it.’

— BRIAN THOREEN

SL: Do you consider yourself to be an artist or a designer? Does it matter to you?

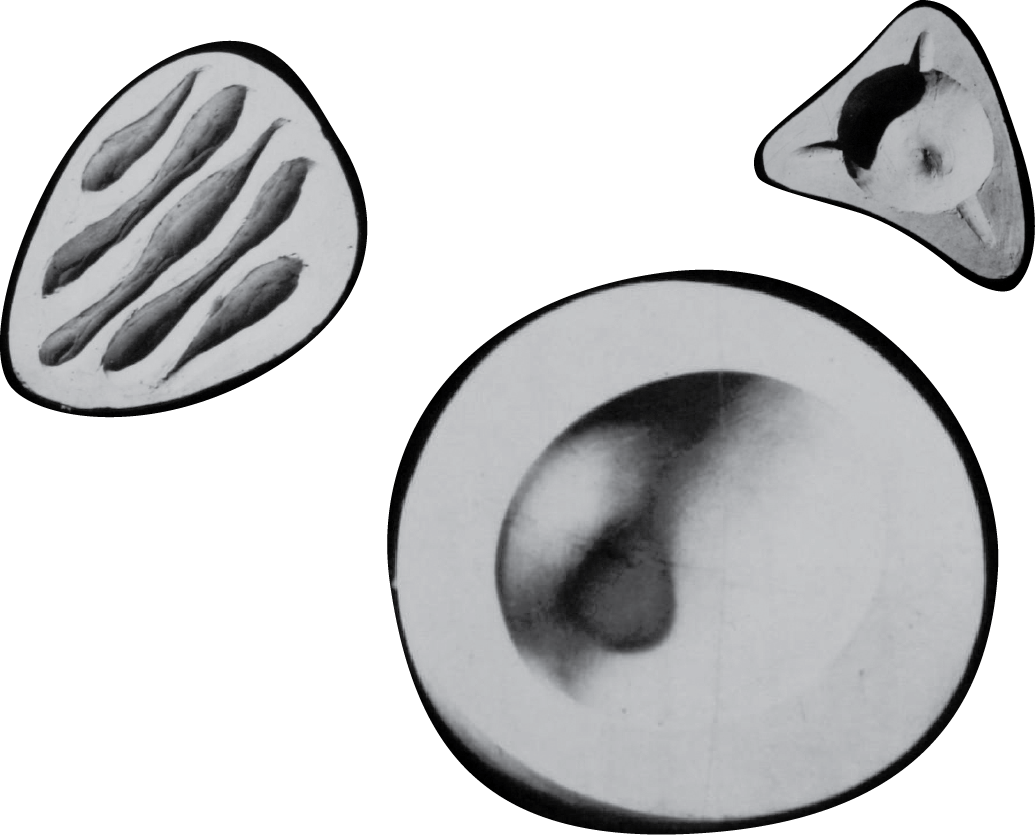

BT: It does matter. I prefer designer in general but both work. It depends on what I am doing. Part of moving to México was about getting back to making nonfunctional work and art. I think the distinction between artist and designer is an important one. When I’m designing, I’m a designer, when I’m making art, I’m an artist. I like the crossover between function and non function or the ambiguity of function—the experimentality between that blurry area. Typically, that defining line is function. There’s a lot of arguments on both sides and I love those arguments. I also think it’s ok to be both.

SL: What are three words that describe your design practice?

BT: Material, process, and intention.

I think material and process speak for themselves. Because my background is in fabrication, materials and process, they all inform my pieces. Intention is something I think about a lot. It relates to your previous question, to function and nonfunction. I think the piece depends on the artist or designer’s intention. Intention is focus, specificity, knowledge and thoughtfulness. I like to think, I like to ponder, I like to let things percolate in my brain for months before I ever do anything about it. I also like working quickly, with a deadline, although in terms of new ideas, designs and processes, these things take time. Intention relates to allowing yourself that time.

SL: Is there a material you’re most excited about right now?

BT: I get asked that a lot and to be honest, there’s never any one at the moment. Currently, I’m working with beeswax, as well as with copper, rubber, glycerin and tar paper. I have no favorites. What excites me is finding new ways for these materials to exist.

For example, the black rubber pieces have a top that locks everything in place, although the ribbon is much looser. The red rubber piece you saw at MASA Inc, which has no top, is much more tightly wound and it holds itself in place through the compact concentric circles. We realized that the top is not needed. So, this piece’s function is ambiguous. You have to bring the function to it through objects like a tray of drinks. My intention was to find a new way for the rubber to exist with itself. It wasn’t about the functionality. It was born out of the idea of a table, but it can also exist as a sculpture.

SL: What are some of your greatest influences as a designer?

BT: Working within the art world and getting to work with artists since young. I remember slinging mud around the gallery with Richard Longing for instance. It was amazing, even though I didn’t really know who he was at the time. I was very fortunate to work with a lot of talented people early on, even James Turrell. That was my education and it taught me to think about how to set up my work and to think about intention.

Also, in LA I came in contact with a project run by a scholar of early French art deco, antiques and painting. In art and architecture school they touch on art deco a bit, but it kind of gets glossed over because the focus is on bauhaus and the early days of modernism in terms of design, manufacturing and repetition. I realized that art deco at that time was all about fabrication, materials, process and the art. The art deco greats like Edgar Brandt and Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann and Rateau were fabricators first and foremost. I relate to that. French art deco is all inlay and macassar ebony, ivory and hand-carved, very intentional, layered, and laborious. It’s modernism, but made the way antiques were made. Once I developed my own design language with my early works, finding ways to meld contemporary art, sculpture and design with art deco was very important for me.

SL: What do you think is one of the greatest myths about the art world?

BT: Contemporary art tends to get hyped and so be seen as frivolous. I think once you’re in it and have some experience within art, you realize that the ‘art world’ is just a bunch of regular fucking people finding new ways to look at the world. The intention of the artist and the art world are separate. When artists intentions are pure, honest and have integrity and thoughtfulness, it transcends the art world.

SL: What inspired your move from LA to Mexico?

BT: I guess México itself did. I was living between LA and New York, and didn’t want to be in either city. I have a son who’s there and I didn’t move until I felt like he was old enough for me to move away. I was spending a lot of time here and while I was falling in love with México, my now partners in MASA, Héctor Esrawe and Age Solojoē, were very generous and included me in everything. I wasn’t yet convinced it was the right place to move for my business, practice, or for my clientele. Then I realized that México is where I want to be, where I am happy. The quality of life here is better than pretty much any other city in the world.

SL: Has the move to México changed your work at all?

BT: México has changed my work in that I like my work to be informed by my environment. The way people fabricate here is different than they do in LA. I have to alter the work to be able to fit what the possibilities are here in terms of fabrication and material availability. It’s changed my work with my copper pieces, for example. I could never have done these pieces anywhere else because México is where hammered copper is traditionally done. Materiality, availability, processes, space, inform my work and that has all changed. But it has not changed in the way of it being more ‘Mexican’. For me, the place or the culture doesn’t have anything to do with my work. I still have the same intentions, the same aesthetic and the same thought process that I always have. What’s changed is the material availability in the space, the light, the quality of life and the pace. I really enjoy the pace of life here. I like to be thoughtful and take my time when I need to. A big part of moving here for me is getting back to a studio in which to experiment and work with my hands.

SL: What is one of the most memorable moments you’ve had here at your studio?

BT: I was living in Age Solojoē’s old apartment in Condesa when I moved here. Right before I was about to sign a lease on a house, my friend Emmanuel from Chic by Accident called and said ‘you gotta go meet my friend Thomas Glassford, he has a crazy space for rent’. I saw this space and I just died. I sold all my furniture and moved from New York. I didn’t have anything to fill the space. I went to Home Depot, bought some saw horses, and an old wood chair Thomas left behind. I had a mattress on the floor for my bedroom, and a door desk for my laptop. I’m saying all of this because my best memory is finally having my own space with nothing in it. I remember sitting at my desk reflecting, looking at the tree that was growing through the ceiling in my studio and just thinking I made the best decision.

SL: What’s your dream project and/or client?

BT: There are many, but my favorite project at the moment is with my business partner Héctor Esrawe. He’s been planning to build a country house and he recently asked me to design it with him. I like architectural projects. I like sculpture, experimental architecture. But my dream project is my own solo show. Having a conversation with my art, design and intention within a space. That’s the purest form.

SL: I feel like the line between art and design gets more blurred in México. Why do you think that is?

BT: MASA started because of that. Before MASA we were all showing our experimental collectible design crossing the line between art and design at places like Zona Maco in the design section. People like Pedro Reyes have done seating and other things in the past. People like Mario García Torres, Alma Allen, who we’re currently working with at MASA were also doing the work. It just wasn’t being represented, there wasn’t a platform for it. In terms of people’s perception of how the city has changed in the last five years is in part because of MASA, AGO, Labor, kurimanzutto and other spaces giving these artists a chance to show design and function related work. Obviously, this conversation has been had for a long time and in many different places, by people like Mathias Goeritz, Barragán and all these creatives experimenting with architecture, design, drawing, sculpture and painting. It’s not a new conversation. MASA didn’t invent it. México is a bit more free in terms of what’s possible than in cities where that conversation was already happening.

Become a MATERIA member to gain access to ‘Close Friends’ stories and anecdotes about Brian’s life and work in México.