A NATURAL AND COSMIC EXCHANGE: CREATIVITY THROUGH THE EYES OF BOSCO SODI

Portraits by Viridiana

Photography by Magaly Ugarte de Pablo and Liz Zepeda

Bosco Sodi is a prolific Mexican painter and sculptor committed to social change through the exchange of creative knowledge. Residing in New York, he works between his main studio in Brooklyn, México City and an open air studio at Foundation Casa Wabi in Puerto Escondido on the coast of Oaxaca. Sodi’s creative origins began at a young age. His mother, a Marxist philosopher professor at UNAM, introduced art as a therapeutic tool to focus his imaginative and curious mind. Ever since, Sodi’s creative practice has developed lock and step with his fascination with nature, material experimentation and cosmic knowledge. Growing up in México City was not unlike Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma, says Sodi — full of nostalgic black and white imagery like fútbol in the streets, hours of unsupervised play at UNAM’s sculpture garden and vibrant Sunday family lunches.

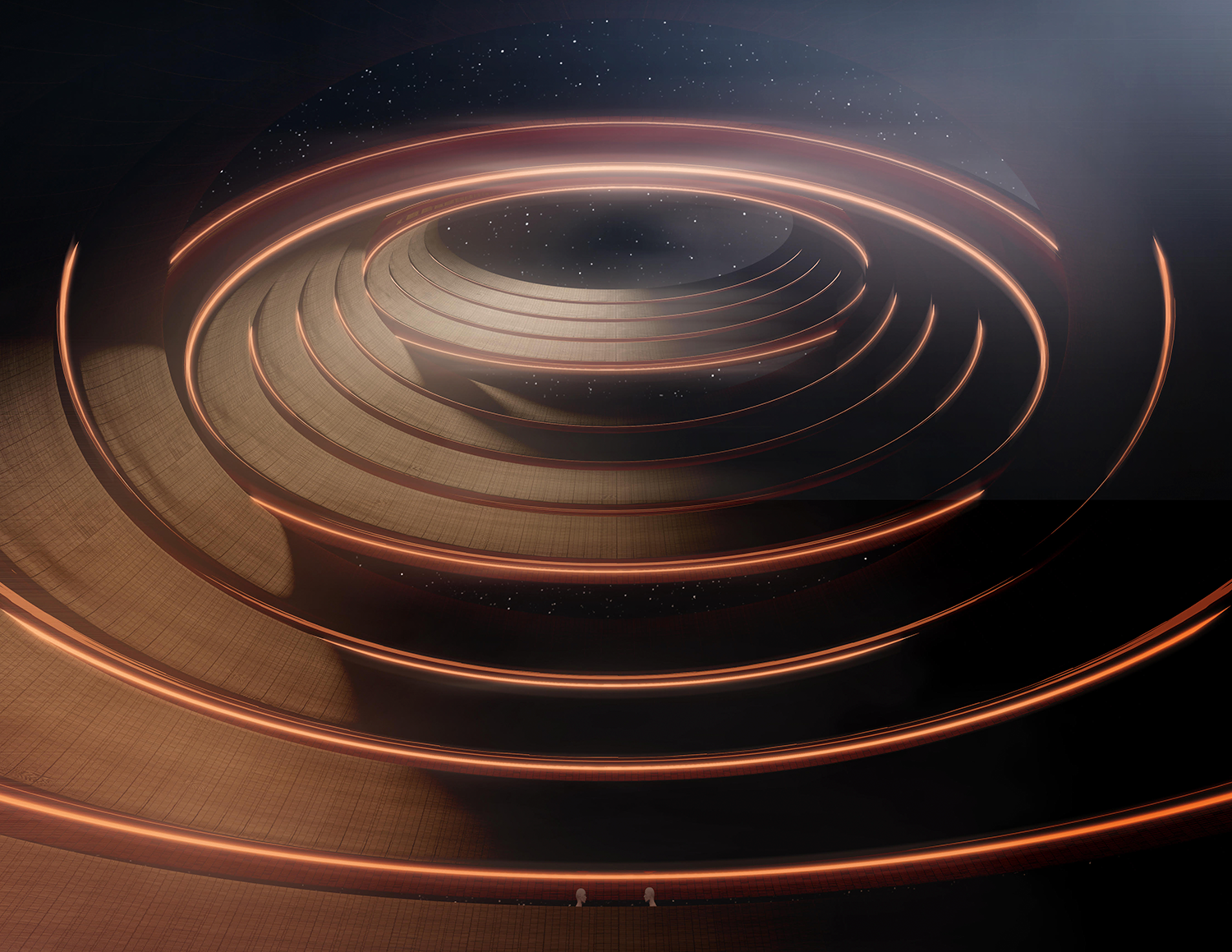

When asked about México’s current art and design scene, Bosco replies that he’s always seen México as the capital for creativity in America. Sodi observes that his home country has just the right conditions that contribute to its creative culture. In 2014 Bosco Sodi founded Casa Wabi, a foundation and artist residency in Puerto Escondido — its name based on the principles of the design philosophy he came to admire. From the age of 12 he and his family went camping on the Oaxacan coast during a time when local and international tourism was still sparse. The massive concrete structure designed by Japanese architect Tadao Ando, sits directly on a 550 meter stretch of Pacific Coastline. The foundation invites artists to share their creative knowledge with members in 14 surrounding communities. ‘If I’m able to help the people who are in my world to have more tools in order to understand life, the universe, their relationship with other humans and with nature, it will be a total success.’ — Bosco Sodi.

The project lends to a collaborative exercise between internationally renowned architects and colleagues. Invited collaborators include Alberto Kalach, Jorge Ambrosi, Gabriela Etchegaray, Álvaro Siza, among others. Each of the collaborators designed functional pavilions across the property that host visitors, artists and school children activating Sodi’s vision: the exchange of knowledge. Sodi recently announced the opening of his new museum in New York’s Catskill Mountains called Assembly featuring work by international artists set in an abandoned dealership re-designed with the help of fellow Mexican creative, Alberto Kalach.

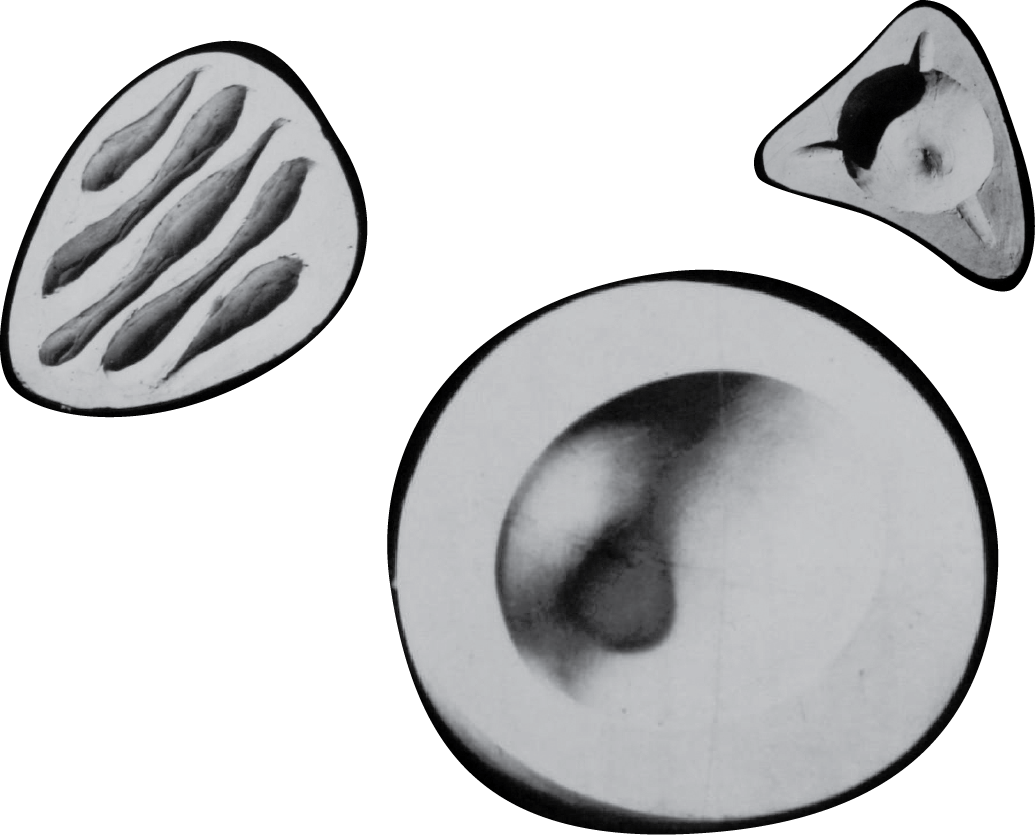

Sodi’s most recent exhibition What Goes Around Comes Around, was unveiled at the 2022 Venice Biennale. His work can also be seen in an ongoing exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art. La Fuerza del Destino features 30 of Bosco’s sphere ceramic sculptures on display through July 10, 2022.

Bosco Sodi sat down with MATERIA Editor-in-Chief, Sarah Len at Galería Hilario Galguera in México City. The discussion focused on his creative origins and influences ranging from Indigenous architectural sites, cosmic presence in film, and how fire, clay and natural materials are part of our DNA.

SARAH LEN: I’m curious about the origins of your name.

BOSCO SODI: It comes from a Salesian saint from Turino, Italy. It’s a saint who my grandmother sympathized with. When she lost her first child during pregnancy she made an offering to the saint San Juan Bosco, that she would name her first child after him if everything turned out ok. She gave that name to my father and he gave it to me.

SL: And what are your origins?

BS: We are from México, three or four generations on my mother’s side. On my fathers side we have a little Italian blood, I’m sure some Spanish and Indigenous too.

SL: You live between México and the States right?

BS: My base is in New York, where my kids go to school and where I have my main studio. I have my foundation and studio at Casa Wabi in Oaxaca. I’m also building a studio [in México City] with Alberto Kalach, in the neighborhood of Atlampa.

SL: You grew up in México City. What was that like?

BS: It was a beautiful time. My mother is a Marxist philosopher with a Master’s Degree in Marxism. She used to give classes at UNAM. My father is a chemist with a PhD from MIT—I grew up in this family that was involved in culture. My grandfather was a cardiologist, known around the world so we were close to concerts, museums, and theater. We come from a family that loves reading, we love cinema, but also during those years we played all day in the streets. I would go walking with no fear, we played fútbol with the neighbors, similar to Roma, the movie by [Alfonso] Cuarón. I grew up in a big family, surrounded by cousins, aunts and uncles. On Sundays, lunch was at my grandfather’s house with 50 people. It was very nice.

SL: What are your thoughts on art and design currently in México?

BS: I think México has always been a capital for creativity in America — sometimes on a bigger scale, sometimes on a smaller scale. We’re in a very special moment. I don’t know the formula, maybe it’s the chaos of the last 30 years, politically and economically speaking. But it’s become a caldo de cultivo. In chemistry, when you want to grow a bacteria you put it in a caldo de cultivo…

SL: Ah like a petri dish.

BS: Yes, the dish is the container. There are very special circumstances that have happened in México since Salinas. For a new generation of artists, including myself and friends like [Alejandro González] Iñarritu, Carlos Reygadas, and other artists—[México] was a caldo de cultivo for creativity. Now we have very good writers, amazing movie directors, and generations of internationally known artists. It has been a very special moment for design and architecture for people like Alberto Kalach, Ambrosi Etchegaray, Tatiana Bilbao, Frida Escobedo. I’m a little bit afraid—it may not be politically correct—to see so many tourists and foreigners living here. I think it’s the end of the curve, like Berlin.

SL: What do you think is the biggest risk?

BS: Things can become very trendy and lose authenticity. It happened in Berlin. When I lived in Berlin there were a few groups of struggling artists, the city was a surprise, it was chaos, total chaos. And now when you go to Berlin, it’s not bad, but it’s the lighter version of a city. When things get very conventional they lose their magic. People want to be here, have their studio here. It is the autumn of México City. I hope not, but the same thing is happening in Puerto Escondido.

SL: You’ve been there watching the change.

BS: It’s part of the evolution of a city. And then of course maybe in a 100 years it will begin again.

SL: As an artist what have been some of your greatest influences?

BS: Since I was very young I loved art, the abstract expressionist, also the Catalan Informalism like Tàpies and all his generation. I was very lucky because my mother loved painting. We had lots of books that allowed me to be in contact at a young age with Arte Povera and Gutai, with the works of Tàpies and Walter de María. When my mother used to give classes at the university, she used to leave us in the Espacio Escultórico at UNAM. We spent afternoons playing there. We didn’t have nannies so my sister and two of our cousins would go, we’d spend the afternoon exploring. We were influenced by the different kinds of materiality found there. We would often go to see the ruins around México and I was really impressed and attracted by the physicality of the stelae. It’s not a painting, it’s not a sculpture, it’s a thing that occupies a very strong place in space, that marks the space.

SL: Tell me about your vision for Casa Wabi and how it came to fruition?

BS: When I was young I was diagnosed with dyslexia and attention deficit disorder. Instead of medicating me, which was very usual at the time, my mother put me in art classes that were kind of therapy for me. Painting and doing art has always been a necessity.

When I thought about how to give back, I knew it had to be in my home country. I’ve been going camping in Puerto Escondido since I was 12 years old, when no one was going there. I fell in love with the place, the energy and the memories, so I decided to do the project in Puerto Escondido working with the local community. I feel a lot of Mexican artists are missing a social commitment. I feel a responsibility to give back, not just in money, but with my energy. Even though I don’t run the foundation on a day to day basis, I get involved in the program and the architecture.

SL: Can you give me a real life example of the impact you’ve made?

BS: We work with 14 low income communities in Oaxaca. During our seven years as a residency we’ve already had 350 artists. We give them a studio, a place to live and we pay for everything. We don’t ask them for work, because I don’t want to have the responsibility of taking care of their work. What we ask them to do is a strong project with the local communities. That’s one of the central lines. For example, when there were no classes during the pandemic, the artists went to the schools and did murals, sculptures, playgrounds. For me it’s always interesting to see the artists learning about the traditions and knowledge from the surrounding communities. I don’t always have a chance to talk to the residents, but they often tell me how amazing it is that the communities are now so used to art.

SL: Have you seen any of the children from the local communities pursue an artistic path?

BS: It’s only been seven years, but yes there are some kids doing photography, painting and sculpture—that’s important, but that’s not how I measure success. I believe that art gives us the tools to understand the universe—and with those tools we are able to change it.

At Casa Wabi we also have a mobile library that goes to the 14 communities to lend books and to read to the kids. We have a cinema. We show them content from Studio Ghibli, Charlie Chaplin, Cantinflas or things like that. We also have a Clay Pavilion made by Álvaro Siza where we invite up to four classes a week for students to reconnect with clay, and hear classical music. They receive an architectural tour of the pavilions, they see all the current shows and artist exhibitions. We give them a fun, cultural day.

We’re constructing a new México City exhibition space in collaboration with Alberto Kalach, where artists who do not have gallery representation can have an opportunity and visibility through Casa Wabi. We also have Casa Wabi in Tokyo where we invite eight Mexican artists a year to experience and understand Japanese aesthetics.

We recently did an open call for the Orchid Pavilion at Casa Wabi, where we are attempting to recover endemic orchids born in Oaxaca. We did an anonymous open call with a jury comprised of Alberto Kalach, Tatiana Bilbao, Carlos Zedillo, Gabriela Etchegaray and myself. We had over 300 applicants and the proposals were amazing.

All the pavilions at Casa Wabi are functional, created in collaboration with talented colleagues. The Clay Pavilion by Siza, the Guayacan Pavilion by Studio Ambrosia Etchegaray are full of endangered plants that we got special permission as a way to reforest the area. When kids come for the day we give them one to plant near their home. We have a chimney made by Alberto Kalach that is going to be the ceramic kiln. Then we have a Compost Pavilion shared between Casa Wabi and the surrounding hotels and houses.

For future projects, we want to create a dictionary cataloging the orchids in the Orchid Pavilion; we’re building a concert hall; developing an important architecture film, and mushroom pavilion—where we educate the community on how to generate healthy diets and a means of income by way of gifting them spores to cultivate.

SL: On the topic of mushrooms, have you done any psychedelics in your practice?

BS: No, my mind is very complex, it’s always running at 300 miles per hour. I’ve done very few drugs in my life because it’s been difficult for me to find balance.

SL: How have cosmic and natural elements influenced your work?

BS: As a teenager I observed an interesting approach to cosmic presence in movies. Then I found the Wabi-Sabi philosophy, and I fell in love. I saw that it was already implemented in many parts of my life. I understood that we are here for just a very short time. You are part of a bigger universe than the one you think you are. When you understand that, you understand the essence of nature, the essence of the real beauty of things. I’ve always been really attracted to nature because it calms me down. We have a house in Upstate New York and I love to be there in the middle of nowhere, where we have chickens, goats—I like all these simple, beautiful things. They represent my search to find a connection to the universe and to nature. Especially now when it’s a daily struggle bombarded by the mobile phone, and the internet. Almost all people live a very similar life.

SL: Where do you source the clay you’re working with?

BS: The clay comes from a community close to Casa Wabi, Llano Grade where they work with little bricks. One of the first residents, Corban Walker, a friend who I used to work at Pace Gallery, introduced me to what the community was doing with clay. Initially the craftsman told me ‘you cannot do such a big volume of clay because it will crack’, but—I love puzzles. So I began to experiment. I hired the same craftsman to work on my studio and we spent one year doing a cube and recovering the process. I love the learning process.

Clay is very familiar to Mexicans. If you think about it, clay has been a companion to humans since the beginning. The first tools and vessels that we created on any continent were made with clay. Museums all around the world are filled with clay. I think it’s a material that we have in our soul.

I was in Upstate New York talking with my daughter, Alba.She asked me ‘why do you love fire?’ I said because it’s in our DNA. When you enter our house, you immediately seek the fire, it’s the first thing our dogs do, get close to the fire. It’s an essential, cosmic connection with clay, with fire, with water, the sensation of diving—those things are in our DNA. That’s why I became so attracted to clay as a kind of materiality.

SL: How much do the spheres weigh?

BS: The one we are bringing to the Venice Biennale weighs one ton.

SL: How long were you in that process of figuring out how to make the spheres?

BS: I’m still in that process. It’s experimentation. It’s interesting to have this kind of non-predictability, of surprise. The whole concept of my work, and actually a concept I try to implement in my life, is a kind of unrepeatability. How the accidents you don’t control, the passing of time, experimentation bring you to outcomes that are not repeatable even with your own hands.

SL: You did speak on this, but is there anything you would like to add to the ethical role you believe artists have socially?

BS: One of the tools that is going to guide us through these terrible times is art. I believe all kinds of art is necessary, but the inclination is not yet very focused. Art is going to be one of the tools that help us through global warming, COVID, we have a big responsibility. But the compass has been lost, there is too much money and emptiness.

SL: What’s the impact that you hope to leave as an artist?

BS: If I’m able to help the people who are in my world to have more tools in order to understand life, the universe, their relationship with other humans and with nature, it will be a total success. At the end we are going to pass away and thinking about the future of your work it’s not logical. Of course I hope my works appear in museums in the future. It’s egocentric, a lot of artists are egocentric by definition.

A special thank you to The Lost Explorer for sponsoring this article and Galería Hilario Galguera for hosting the interview.