ENTERING THE FOURTH-DIMENSION WITH RAY HOWLETT

Photography courtesy of Ray Howlett Studio

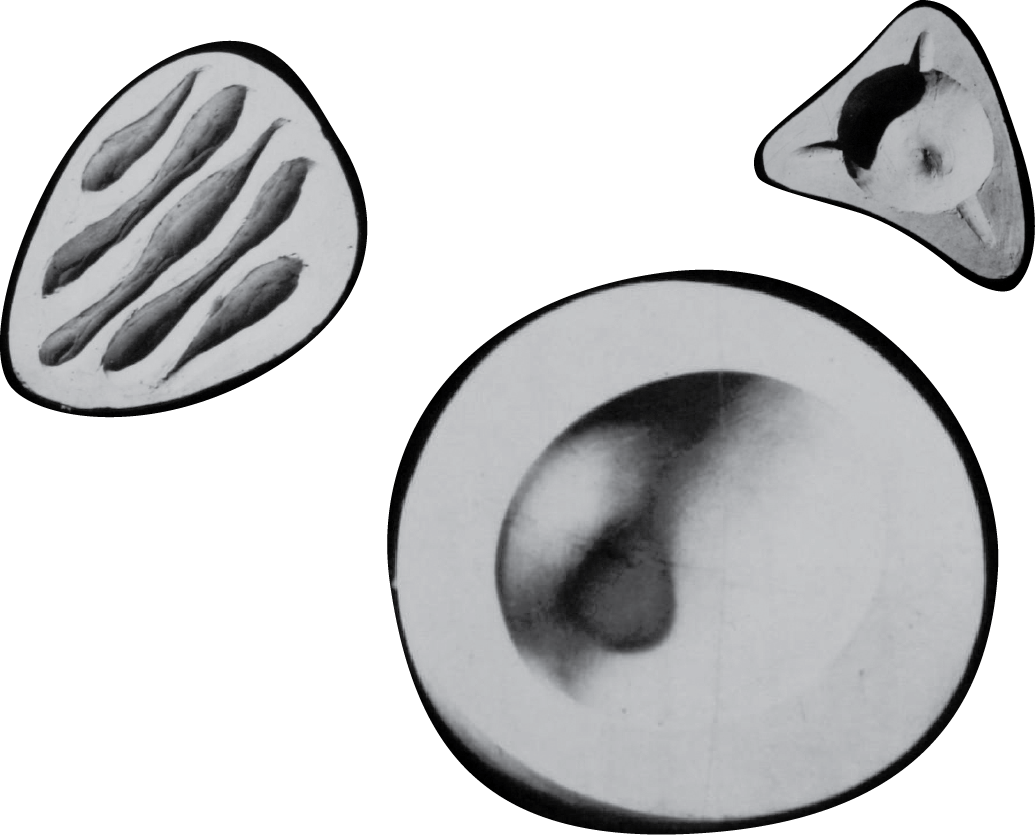

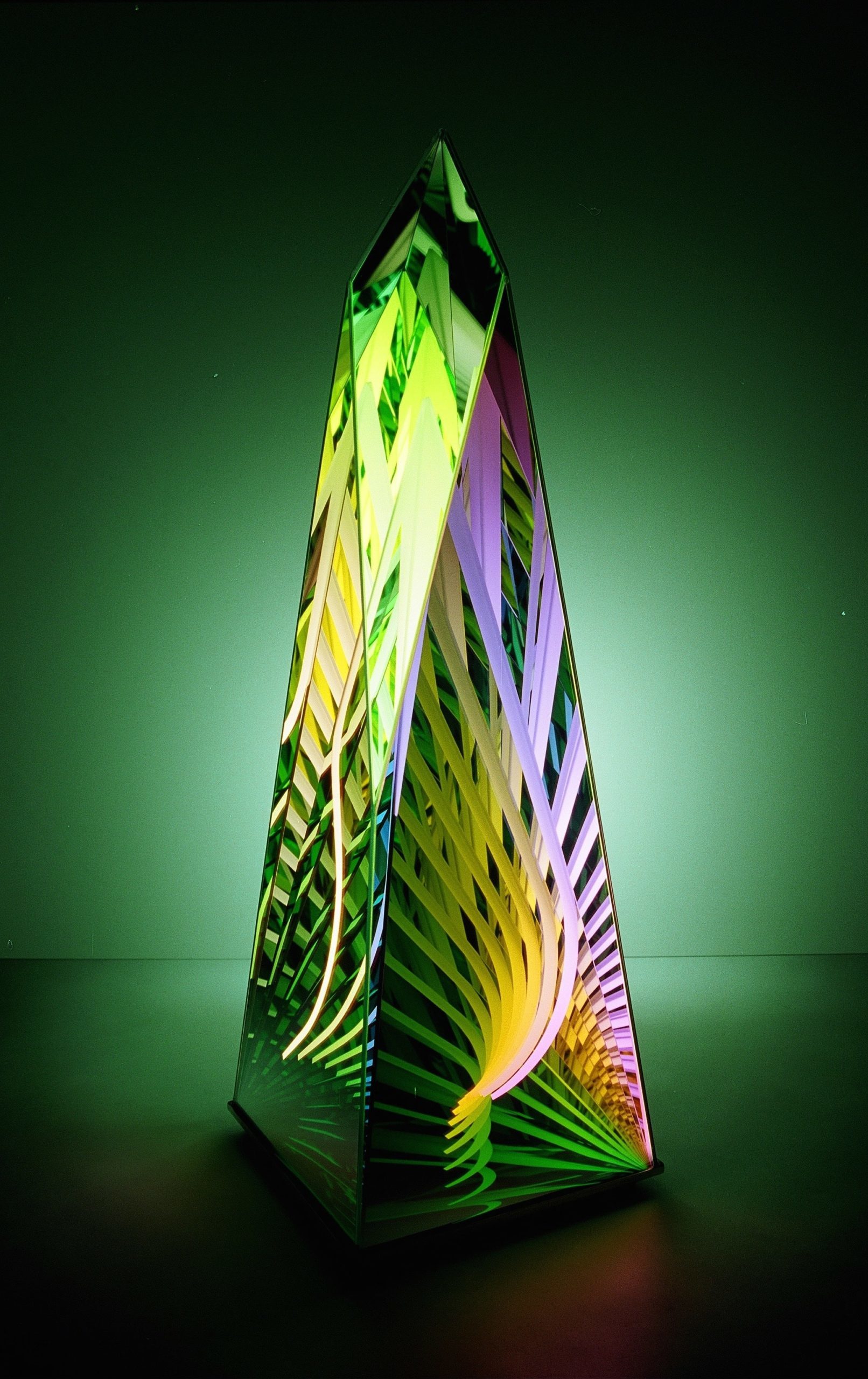

MATERIA spoke with artist Ray Howlett in his cabin among the pine trees of Southern California. He describes himself as a camper and a recluse, as what he enjoys the most is having the space and time to focus on his practice. Howlett is in his eighties now and is known for being a pioneer of infinity light sculptures. Working with reflection, mixing forms and movement depending on the perspective, to reveal worlds within worlds based on meticulously built structures. Each piece contains unseen manifestations to be discovered.

Ray Howlett talked to Sarah Len, MATERIA’s Editor-in-Chief about the technology he has perfected throughout the years and how he has managed to live the life he desires. His need to be original is so strong he doesn’t even copy past versions of himself. Ray’s inspiration comes from within, and his main drive has always been to keep on creating. Now more than ever he’s prepared to show the world the masterpieces he’s been developing over the last 50 years.

Sarah Len: Can you tell me what is going on behind the curtain to create these pieces?

Ray Howlett: It is an accumulation. When I went into college, I enrolled in engineering. It has always been so interesting to me, but I didn’t think I was smart enough to be an engineer. So, I changed my major to art. After I graduated I realized that what I had learned didn’t have much to do with real art. I even threw my fraternity ring into the bushes one night. That was when I became a full-time artist. It was around 1970 when I also started my experiments combining reflective surfaces with electric light. They were so crude, but I thought “this is fun”.

My biggest growth was in technology. My art and engineering ended up being married. The same amount of engineering is in my work as is art. It’s like a dancer. A great ballet dancer does a jump and a move and it’s so perfect. It looks effortless. You don’t see all the years of learning where it’s perfected. Now after what? 50 years.

“When I get the image of the form that I want to build in my head, I already know what it is going to do. But when I build a structure around it, I don’t know what the reflections are going to look like. Until I turn on the lights for the first time I don’t know what’s gonna happen inside.”

— RAY HOWLETT

SL: How did you get into working with glass?

RH: Through experimenting. That’s how I learn. Glass has been with me since 1960 when I was doing photography and moved to California. I started doing some strange stuff with flat sheets of mirror. I could make magic happen with them. From then on, everything was about mirrors and electric light. It just rang a bell in my heart. So I committed to that formula.

SL: Do you typically know the outcome or does it reveal itself along the way?

RH: When I get the image of the form that I want to build in my head, I already know what it is going to do. But when I build a structure around it, I don’t know what the reflections are going to look like. Until I turn on the lights for the first time I don’t know what’s gonna happen inside.

There are certain things with the formula of angles – mirrored angles together do a certain thing. But if I change the angle, something different happens. Every time I make a piece, I play with the angle of the mirrors coming together. I’ll do a pyramid one time or an octagon at another. But if I change the imagery and electricity, it changes everything.

“All along, my art has been about participation with the viewer. I’ve designed it so that they have to participate to complete the work. The sculpture is a three-dimensional structure. But, if you take a body – a person – and they move around looking at a piece for some time, they become part of it. The viewer is essentially the fourth-dimensional element.”

— RAY HOWLETT

SL: I read something about the fourth dimension in your pieces. Would you explain that?

RH: All along, my art has been about participation with the viewer. I’ve designed it so that they have to participate to complete the work. The sculpture is a three-dimensional structure. But, if you take a body – a person – and they move around looking at a piece for some time, they become part of it. The viewer is essentially the fourth-dimensional element.

SL: I love that. Going back in time a bit now, the Light and Space movement starts mainly in the sixties, right?

RH: Yeah. I mean, I started with light and space in 1964 with my high contrast photography on glass with a painting behind it. The viewers moved around it and the imagery would shift with their movement. The viewer’s participation, using mixed media, science, light and space was the Light and Space movement. But I didn’t know about it. I’m pretty much a recluse (laughing).

SL: So how did you see yourself fitting into that? Do you have any muses or specific people that inspired you from that movement?

RH: Not really. I’m so self-inspired that I don’t feed on somebody else’s art. I don’t want to copy them. In the sixties, op art was mostly two-dimensional optical illusions on canvas. My art is about optics and physical illusions.

When I discovered the Light and Space movement, I said to myself: “I’m a Light and Space artist”. Our art was so similar, especially with Larry Bell.

SL: What about now? You moved out to the pine mountains in California. How do you reconcile the need to stay present in the art world versus this escapism that I think calls many artists?

RH: I don’t need to get validation from the outside world. But I do like to do an exhibition and then let the public come and see it. A museum show. People can hang out, enjoy a whole body of art and get a sense of what the artist is about. Museums have been the best to work with for me. The ones I’ve had the fortune to work with didn’t have much of a budget to pay though, as they were all small. If it wasn’t because of living in Nebraska – paying no rent – I wouldn’t have been able to do these shows.

“I wanna go inside, I wanna be inside the sculptures and I haven’t been able to build one where I can fit.”

— RAY HOWLETT

SL: Most of your career was in Los Angeles – Santa Monica and Topanga, right? Then you returned to Lincoln Nebraska in 1995. What changed in your perspective when returning home?

RH: The best thing that ever happened to me in my career was to return to Lincoln. My dad had just died, my mom was lonely and I was free to move. I was able to have time to devote to my art again. I had to spend more time when I was in LA trying to sell in gallery shows and doing household stuff.

When I moved back to Lincoln, my mom took care of the house. I also stopped working with galleries. They’d steal my art. It was terrible. I’d take my mom on vacation. I’d drive her wherever she wanted to go. And sometimes I’d stop and make a presentation to the museums on the road. My mom said people can’t understand my art unless they see it and participate. So after that – when I knew we were hitting the road – I started making appointments to show my sculptures. In 10 years, I made a couple of hundred presentations all over the country.

SL: What is something you wish that gallerists and curators could understand about artists or could offer them?

RH: I’ll give you a good example of how I wish that museum curators and directors were more attuned to what the artists have to go through. It happened on one of my trips from LA to a Texas museum. The director loved my art and he said, “How about doing a piece the size of the room?” I mean, how the hell could I afford that? I didn’t have the money to produce a piece of art like that. He didn’t realize that saying that to me was the most frustrating thing. I already couldn’t fulfill what I wanted to create unless a patron came.

SL: What if you had that patron today? What would you create?

RH: I would make an infinity walk-through with a series of smaller module units. Also an authentic traditional pyramid style of my sculptures– big enough so that you could walk inside of it. I wanna go inside, I wanna be inside the sculptures and I haven’t been able to build one where I can fit.

SL: And finally, I’m so curious how your piece ended up on Star Trek?

RH: I was thinking I’d like to get something in a movie. Then my friend John told me about this company called Hollywood Prop Shop. They work with the film industry and when someone’s gonna do a film, they hire a set decorator to get the props. They chose some of my work. I’ve been in maybe 20 different movies, Star Trek was one of them.