THE DECEPTIVE SIMPLICITY OF MOCK STUDIO

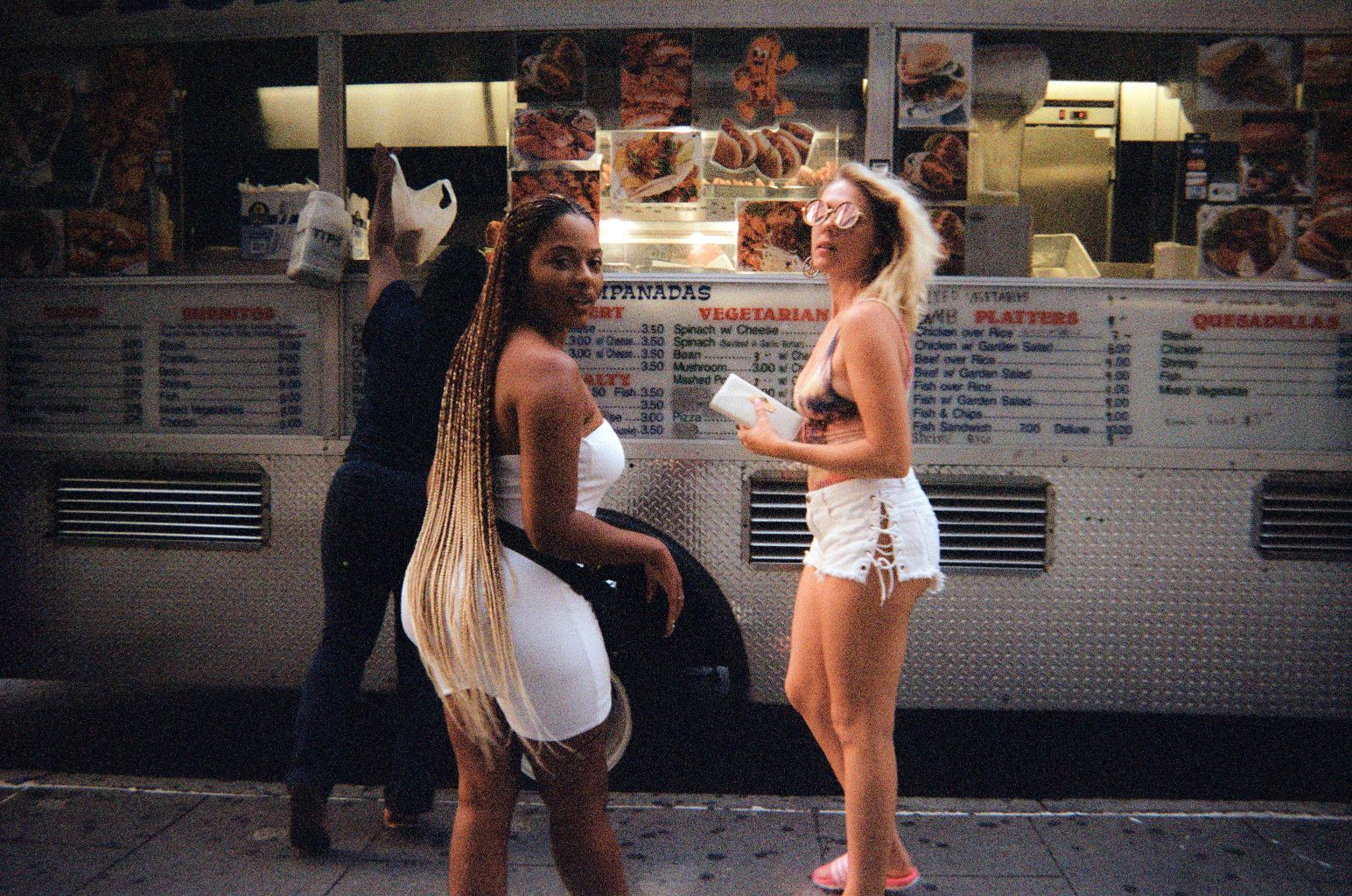

Photography by Sean Davidson

On its site, the Brooklyn design firm Mock Studio describes its aesthetic as understated. That’s one way to define their beautifully pared-down approach to everyday furniture and installations. But you could also describe the young duo as intrepid risk takers — the kind of furniture designers who find keeping it simple nothing less than a welcome challenge.

Helmed by Brooklyn-based visual designer Masha Osorio and architect Christian Kotzamanis, Mock Studios was founded in 2021 as a solution to the lack of approachable objects for everyday use, made using readily available materials. They yearned to streamline production while retaining the purity of their materials. And if they could pull it off while somehow reducing waste? All the better.

MATERIA contributor Jill Krasny spoke with Kotzamanis and Osorio by email to delve into their distinctive practice. Here, the furniture makers share their thoughts on doing more with less, the edible appeal of “buttery” Mock Yellow, and the allure of Robinson Crusoe’s survivalist lifestyle.

Photo by Mateo Arciniegas

Jill Krasny: Tell us how you met and started designing together.

Christian Kotzamanis and Masha Osorio: Our relationship started socially, but we soon realized that we were very closely aligned in terms of our aesthetic and the things we liked, so we started designing together. At the same time, we had very different skills, so we thought we could complement each other very well.

JK: Mock Studios was born out of the desire for “approachable everyday objects, put together using readily available materials and simple fabrication techniques.” Why did this matter to you and why was it important to make this type of product?

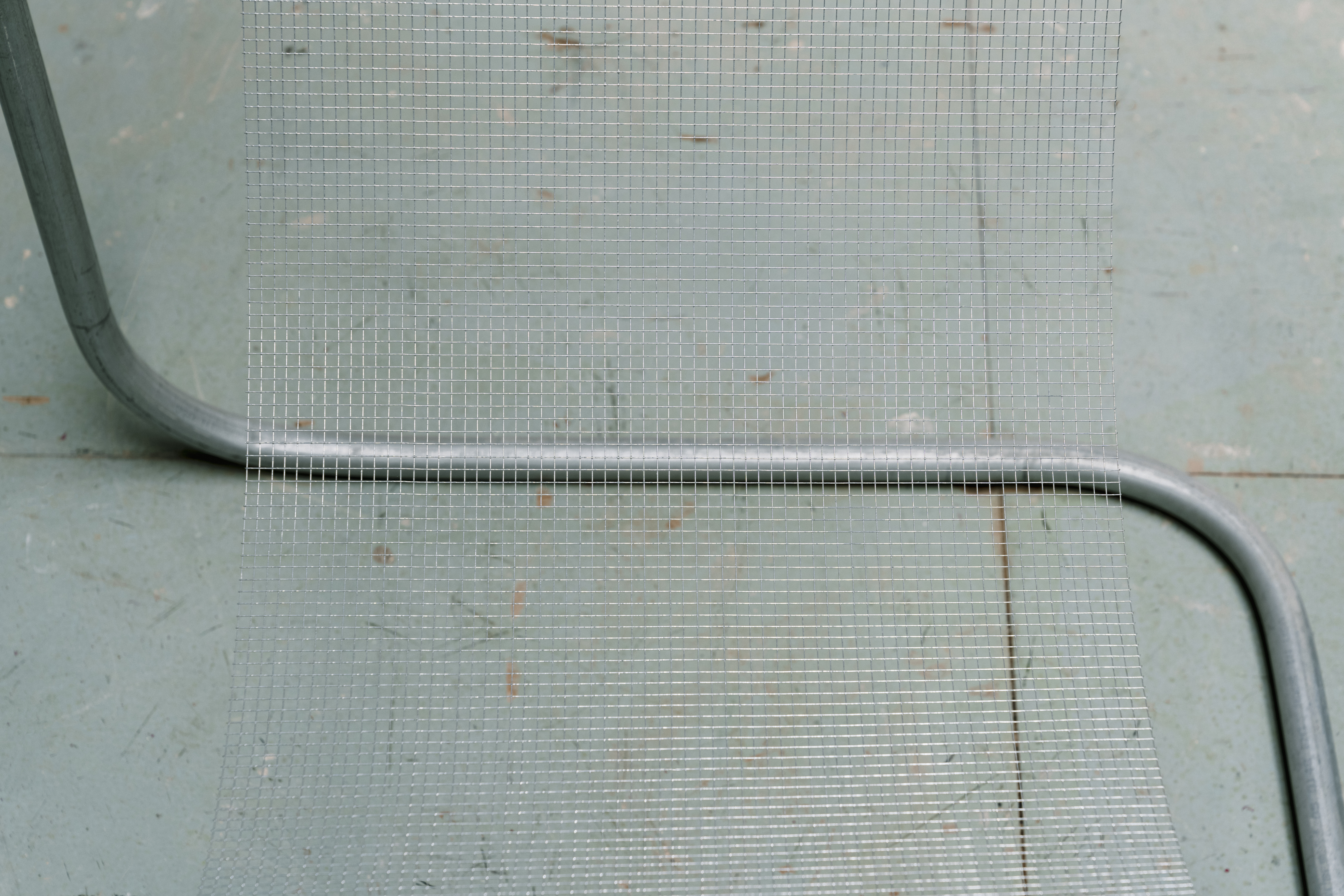

CK & MO: We like the challenge of designing with limited resources; it can be more rewarding to take something of little value and elevate it through design. Simple processes can be applied to ordinary materials to great effect, and this is a guiding force in our work. We are always striving to reduce the overall energy that goes into a project by designing things in a way that allows them to come together easily. This allows us to do more with the resources that are available to us and to create the most value with the least investment. It’s a practical consideration.

JK: You’ve previously described your philosophy as reductionist. Tell us more about what that means and why you strive to emphasize the process more than the product.

CK & MO: Most, if not all, of our work involves leaving materials in a relatively unchanged state to how we found them, which stems from our philosophy of doing as little as possible; we try to avoid overprocessing things. We want to make things easy for ourselves by choosing materials we really like from the outset that don’t need to be altered. Where we invest most of our energy is in simplifying our process for any given design brief and in distilling ideas down to the most important features.

”Most, if not all, of our work involves leaving materials in a relatively unchanged state to how we found them, which stems from our philosophy of doing as little as possible;”

– Christian Kotzamanis & Masha Osorio

JK: From a fabrication perspective, is there a challenge to maintaining the purity of a material? I’d love to hear some examples of how you strive to do as little as possible with maximum impact.

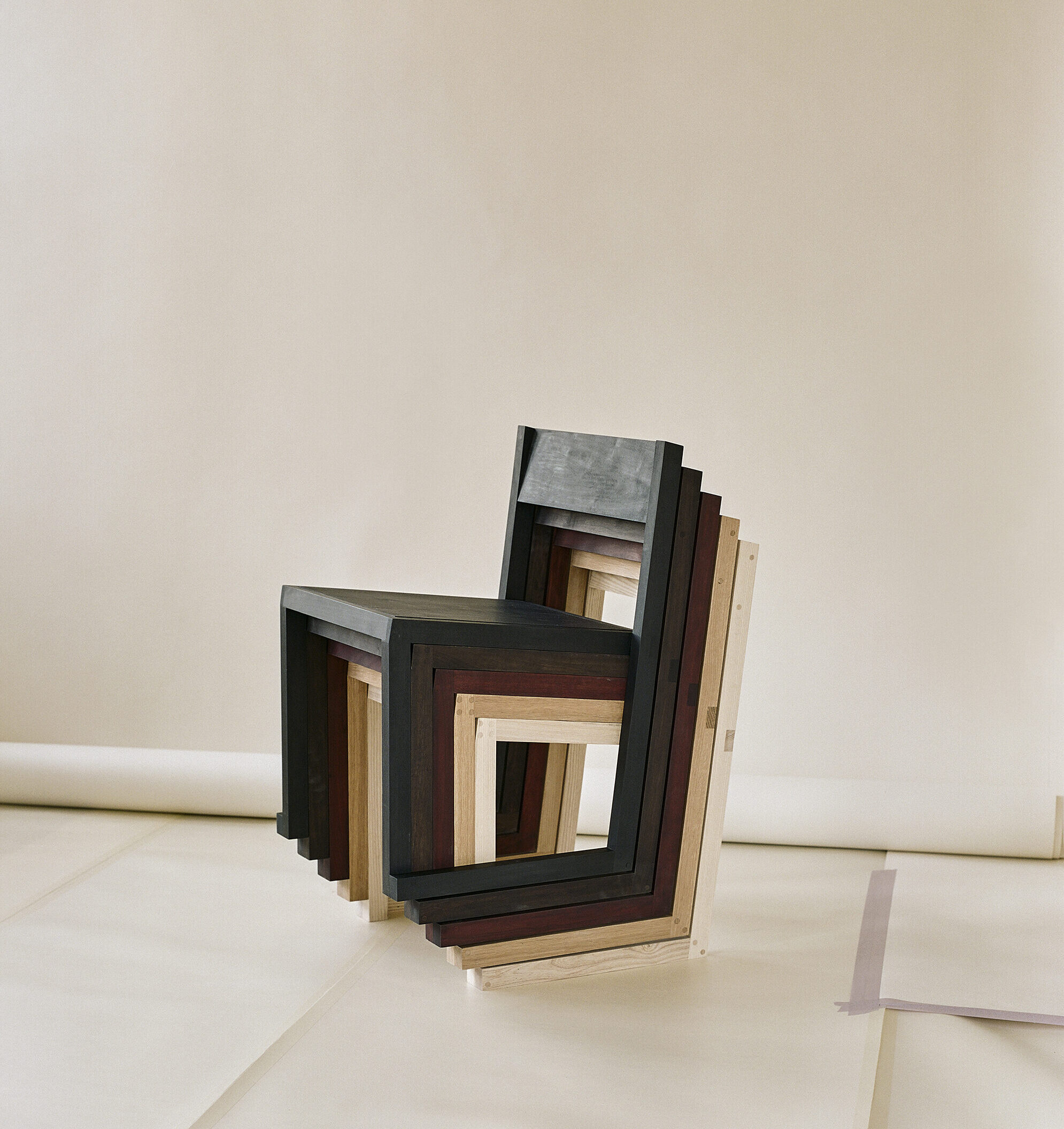

CK & MO: Our Miter series assumes that any sheet material can be applied to its construction, and there are many other pieces we have designed that use only sheet material, however, sheet materials are already heavily processed. So when we talk about purity, we are referring to the material in whatever state it was when we got our hands on it.

Another example of this is the Shear Bench, which is prepared in much the same way as you would prepare a rough sawn wood plank for any traditional carpentry project — it is milled down, squared, and turned into a flat consistent piece of stock material; that is the final bench top.

The legs are made from the offcuts of the same piece but sawed and mounted at an angle for structural stability. The connections are all done using a dowel and glue joint, and that’s the final piece. We didn’t even sand the faces, but the proportions, spacing of elements, and the silhouette are all very carefully considered.

JK: When you start a new project, where do you begin?

CK & MO: We like to think of our studio as designing processes rather than objects. Objects are the end product, but the process is always where we start. We are interested in the idea of repetition and variation on simple themes; sometimes we will design a piece as a result of a new fabrication method we have discovered, and sometimes it is a material we came across that we like. In a sense, a new project is usually an opportunity or excuse to explore an idea that may already exist.

JK: Your first solo show had some stringent parameters: Everything was made by you, in your workshop, using locally sourced materials and primitive tools. Why were these limits important?

CK & MO: This approach is important to a lot of makers, it provides more control. In our case, we like the independence that it brings and the freedom of not having to rely on outsourcing. We sometimes fantasize about a Robinson Crusoe lifestyle, whereby the means are strictly defined by the tools and materials available, in a way that forces you to be more resourceful and to pay more attention to details.

JK: What draws you to the butter yellow color you’ve dubbed Mock Yellow?

CK & MO: It can work well both as a background color and an accent color. It’s a color that, at first glance, you’re not quite sure what to make of it. It lives in the hinterland between white and yellow and has a warmth and luminescence to it; there is also a smooth, buttery, and almost edible quality about it.

JK: Some of your pieces seem very utilitarian and practical for creatives and their studio spaces — e.g., the Background Display Cart or the Domino Shelf. Who were these designed for, and do you see Mock creating more work for designers?

CK & MO: We really like designing for designers; the two pieces you mentioned were a commission for a photographer. However, we will design for anyone. What is important is to find common ground with whoever we are designing for, and sometimes that pushes you in a direction that you otherwise may not have gone and leads to something unexpected, and that can be a good thing.

”We sometimes fantasize about a Robinson Crusoe lifestyle, whereby the means are strictly defined by the tools and materials available, in a way that forces you to be more resourceful and to pay more attention to details.”

– Christian Kotzamanis & Masha Osorio

JK: If you could fill the endless Shear Bench with your dream team, who would be sitting on it?

CK & MO: In no particular order: Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Dieter Rams, Benoit Lalloz, Max Lamb, and Anne Holtrop.

JK: How do you see Mock Studios’ practice evolving in the next year or so? Where would you like it to go from here?

CK & MO: We see ourselves continuing to do more of the same and letting things take shape organically. So far, we have been focused on building prototypes that are repeatable, and they could be produced at scale with relative ease. We are currently working on our next collection, which is an evolution of our first collection and just pushes forward some of the ideas we have already been exploring.