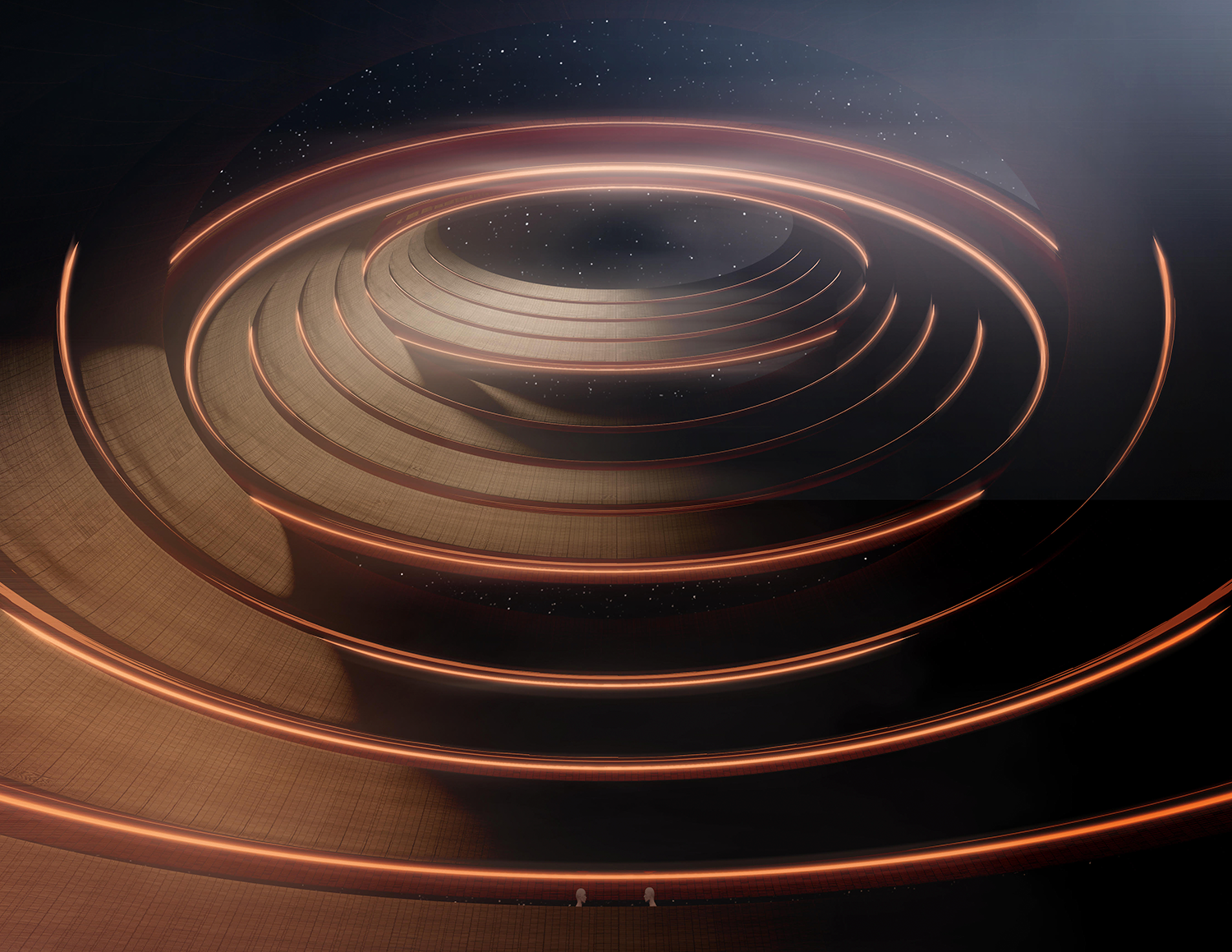

In Santos de Nada (Saints of Nothing), light becomes a way of holding what cannot be resolved. Originally presented as a 2025 solo exhibition by Pol Agustí, the project was shown by AGO Projects in collaboration with ZAK+FOX in New York, bringing together a body of sculptural lighting works that sit between design, ritual, and material memory. Built from discarded fiberglass molds once used to reproduce Catholic icons, the works draw from fragments never meant to be seen, only to serve and then disappear.

In the hands of Agustí, a Spanish-born, Mexico City–based designer whose practice spans furniture, lighting, and spatial work, these molds are reactivated through careful construction and warm illumination. Trained in design and shaped by years working in production design for film and advertising, Agustí brings a deep sensitivity to atmosphere, material, and gesture. Here, those instincts are distilled into objects that hover between utility and ritual. What emerges is not a commentary on religion, but a meditation on belief as lived experience, on spirituality untethered from doctrine, and on the quiet power of presence.

Developed in Mexico, where Catholicism, indigenous traditions, popular devotion, and everyday ritual coexist without hierarchy, Santos de Nada reflects a cultural landscape that allows belief to remain fluid, intuitive, and deeply personal. Relocating to Mexico marked a turning point in Agustí’s practice, shifting his focus away from speed and spectacle toward slowness, domestic life, and material attentiveness. His work draws from this openness, as well as from personal experiences of grief and ritual, translating them into lighting and furniture that function less as declarations and more as companions, offering space for pause, reflection, and attention.

In this conversation, Agustí speaks about arriving in Mexico as a catalyst for rethinking spirituality, about lighting as gesture rather than spectacle, and about the role objects can play in holding memory, intention, and care. Moving fluidly between furniture, lighting, and ritual, his practice suggests that devotion need not be loud or fixed. Sometimes, it exists simply in staying with things long enough for them to deepen.

Sarah Len: Santos de Nada is a title that feels both poetic and unresolved. What does it mean to you, and how did this body of work begin?

Pol Agustí: Santos de Nada began in a very casual way. I was collecting these molds without a clear intention, mostly because I felt they produced a very particular and beautiful light in my home. At that point, it wasn’t a project; it was more an intuitive accumulation.

When I started preparing my first exhibition, La Corucha en el Tetecua, which took place in my own house, I realized I didn’t want to include any lamps that weren’t made by me. That’s when I began to properly work with these molds I already had and to design bases specifically for them. Until then, they rested on found objects from flea markets or second-hand shops, but making the bases became a way of committing to them, of giving them a body.

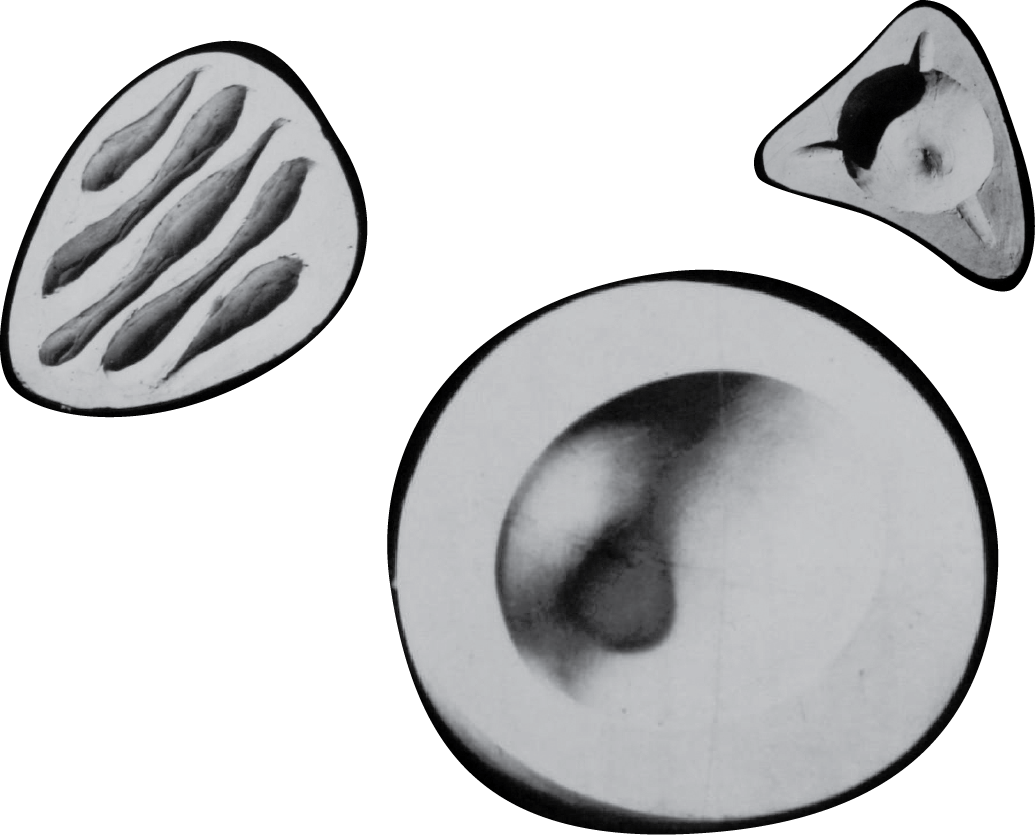

Many of these molds come from church restorations. The people who produce them often work repairing religious sculptures, and what remains are fragments: hands of saints, doves from the Holy Spirit, broken or discarded elements from Catholic imagery. These objects already carried an absence within them.

The title Santos de Nada doesn’t explain; it suggests. It speaks about a loss of faith, but also about the possibility of keeping a sense of spirituality alive without devotion or dogma. For me, lighting these forms is a way of illuminating memory, absence, or a question toward the invisible. Perhaps lighting a void is also a way of praying. Even without knowing to whom, we continue to send light toward something beyond.

In that sense, the project reflects what I encountered when I arrived in Mexico: a very natural coexistence of beliefs, rituals, and symbols. A space where a spirituality without rigid rules feels not only possible, but valid.

SL: Much of your work seems less concerned with belief systems and more focused on relationships between bodies and objects, hands and materials, and light and space. When belief is no longer the central structure, what takes its place?

PA: I think my work is still deeply connected to belief, but not to any specific dogma. It is more about belief as a lived, personal experience. Much of it was created around a ritual, around a funeral I organized after the death of a close friend. Working through that process helped me navigate grief, and translating that experience into objects allowed me to stay connected to her presence in a very concrete way.

With Santos de Nada, this idea extends into the domestic space. It is about having personal altars at home, objects that don’t impose a religion but allow for moments of reflection, remembrance, or quiet connection. Many of the pieces come from molds linked to religious imagery, but what interests me is how they can be reactivated in a more open, non-dogmatic way.

The Micho seating system continues this thinking. It is a series of individually crafted chairs I designed after the death of a close friend, conceived as an homage to her—each seat made as a place to honor her presence, to reflect, manifest, and to hold a kind of soul of its own. Recently, a friend stayed in my house while I was traveling and told me she had been spending time with my new aluminum pieces, consciously manifesting things while sitting with them. In just a couple of days, several of those intentions seemed to materialize. I like to think of these objects as devices or structures that create the right conditions for these kinds of practices to happen.

In the end, what replaces belief as a fixed structure is human presence: relationships, conversations, shared experiences. My work is always connected to the people around me, those who are still here and those who are no longer. I’m constantly inspired by the emotional and almost magical quality of human connections, and that, more than any system of belief, is what truly sustains my practice.

SL: The lamps are made from discarded fiberglass molds, objects designed to reproduce religious icons, yet never meant to be seen themselves. What drew you to these molds as the starting point for the work?

PA: The starting point was very simple. These molds were objects I kept encountering in the workshops of sculptors I worked with while doing production design. I spent long hours in those spaces, and during quieter moments I would wander through dusty storage rooms filled with forgotten molds.

It reminded me of walking along a beach, collecting stones or shells and imagining what they could be. It’s a game I’ve played since I was a child, often with my mother: finding forms, holding them, projecting stories onto them. Working with these molds feels like the industrial version of that same instinct, playing with found shapes on a different scale and in a very different context.

I was drawn to their material presence, the translucency of fiberglass, the way light passes through it so softly. These were objects made to serve another purpose and then disappear. Giving them a second life felt natural, almost intuitive.

When illuminated, they stop being tools or leftovers and become something else entirely. The work grew from that simple gesture: recognizing potential in forms that were never meant to be seen and allowing light to reveal it.

SL: You’ve spoken about arriving in Mexico as a turning point in your understanding of spirituality. How did being here, with its religious landscape, syncretism, and popular devotion, reshape your thinking?

PA: Growing up in an atheist household, spirituality was never presented to me as something structured or fixed. It wasn’t something I rejected, but it also wasn’t something I had a clear place for. Living in Mexico changed that relationship completely. Here, I encountered a landscape where Catholicism naturally coexists with indigenous traditions, magic, popular devotion, energy, rituals, and everyday practices like spiritual cleanses.

What moved me most was seeing how all of these belief systems overlap without conflict. There is no urgency to define faith precisely or to commit to a single framework. Belief feels more intuitive and more lived, something woven into daily life rather than organized around doctrine. That coexistence made me feel comfortable with spirituality for the first time, not as an obligation, but as a space you can enter and leave, question, or simply feel.

Rather than pushing me toward a specific belief, Mexico helped me understand that spirituality can be fluid and personal. It can exist without hierarchy or dogma. That openness deeply shaped how I think about ritual, presence, and the role objects can play in holding memory, intention, or energy.

SL: The lamps are constructed with local woods and visible joinery, without disguising structure or seams. Why is it important for the process to remain legible in the final object?

PA: For me, the wooden bases are also a space of learning. I didn’t come from a woodworking background, so each piece is part of an ongoing exploration, understanding the material, its limits, and its logic through doing.

I’ve always been drawn to objects where construction is not hidden. Leaving the joints, seams, and connections visible feels honest, but also beautiful. There is something very satisfying about understanding how an object stands, how it is held together.

Traditional Japanese woodworking has been an important reference in that sense, not in a literal way, but in its respect for technique and in how joints become part of the language of the object rather than something to disguise. I like the idea that the process remains readable, that the making is present, and that the object doesn’t pretend to be something it’s not.

SL: Lighting plays both a functional and symbolic role in your work. What do you think about light as material, as metaphor, as gesture?

PA: Light plays a very important role in my life and in my work, first on a very practical level. I’m extremely sensitive to it. Whenever I travel around Mexico by car, I always carry small boxes of warm, low-intensity bulbs with me. Wherever I stay, I need to be able to change the light immediately. White light feels too harsh to me. Warm light creates calm, intimacy, and a sense of presence.

But light is also deeply symbolic for me. Turning on a lamp feels close to lighting a candle, a small, intentional gesture you do for someone else, to mark an important moment, to remember someone, or to accompany a feeling. It’s a simple action, but one that carries care, attention, and meaning. I don’t want my lamps only to illuminate a space; I want the act of switching them on to feel like a moment of connection.

A book that resonates strongly with me is In Praise of Shadows by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki. It helped me understand light not as something that needs to reveal everything, but as something that exists in dialogue with shadow. Tanizaki writes about softness, penumbra, and warmth, about how beauty often lives in what is suggested rather than fully shown. That way of thinking feels very close to my relationship with light.

For me, light is not about clarity or truth. It’s about presence, atmosphere, and gesture, about creating spaces where people can feel, remember, or project something of their own.

SL: Much of your work seems to resist spectacle, favoring slowness, restraint, and attention. What do you think about pace in your creative life?

PA: At this stage of my life, I’m consciously practicing letting things unfold. I’m trying not to impose rigid timelines on my collaborators anymore, but instead to ask them how much time they actually need. I allow myself time to research, to travel, to observe, and to move in closer alignment with what I feel is a more natural rhythm for making.

This shift comes from contrast. I spent about seventeen years working as a production designer in advertising and film, in a very accelerated environment where everything was always needed “for yesterday.” That period taught me a lot. I learned how to multitask, how to respond quickly, how to operate under pressure, and I’m grateful for that training. But it’s also a rhythm I no longer want to live inside.

Now, when I notice myself speeding up again, I try to stop and remind myself why I stepped away from that world in the first place. Slowness, for me, is not about resistance or refusal; it’s about attention. It allows space for mistakes, for detours, for things to evolve naturally rather than being forced into shape.

That said, I don’t feel opposed to spectacle. I still enjoy it, and I still like humor, lightness, even a bit of theatricality. What has changed is the pace at which things happen. I’m more interested in flow than urgency, in process rather than immediate results. That balance, between experience, intuition, and timing, is where my creative life feels most honest right now.

SL: In a time of overproduction and constant visibility, your work reclaims what is discarded, overlooked, or unseen. Do you see this as a political gesture, a spiritual one, or simply an honest response to the world around you?

PA: I’m generally very open when it comes to different conversations and interpretations, but there is one point where I’m quite firm. In the world we’re living in today, recycling is hot. I don’t really see how it couldn’t be.

With the lamps, what interests me is not only recycling an object, but also recycling a form. These fiberglass molds already carry a history. They were created to reproduce something else and then left behind. By bringing light into them, that history is reactivated. I’m not just reusing a material, but illuminating something that was meant to remain invisible.

The same thing happens with my aluminum pieces. I’ve started melting down Coca-Cola cans and transforming them into furniture. There’s something very satisfying about seeing such ordinary, disposable objects become solid and lasting forms.

And the same logic applies to my clay furniture. Knowing that these pieces can one day break and simply return to the earth, without added materials or complex processes, also gives me a sense of calm and responsibility.

I wouldn’t call recycling a manifesto in my work, but it is something I take seriously. If I’m going to make objects that stay in the world, it matters to me how they’re made and how they might one day disappear.

SL: Through material, light, and restraint, Santos de Nada reminds us that attention itself can be a form of devotion. What are you most devoted to these days?

PA: These days, my devotion is quite simple and very grounded. I’m devoted to staying steady, to showing up, to working consistently, and to taking care of the people around me. My friends, my collaborators, my chosen family.

Maybe it has something to do with being a Capricorn, believing in time, in patience, in building things slowly and with commitment. I’m drawn to continuity rather than intensity, to processes that grow through repetition, care, and presence.

If there is a belief at the center of my work right now, it’s a belief in constancy, in staying with things long enough for them to deepen, and in understanding attention itself as a quiet form of devotion.

For inquiries about this collection please contact sales@ago-projects.com or info@polagustistudio.com.