PROPORTION, LIGHT AND SPACE: DONALD JUDD AND THE ENIGMATIC LURE OF MARFA

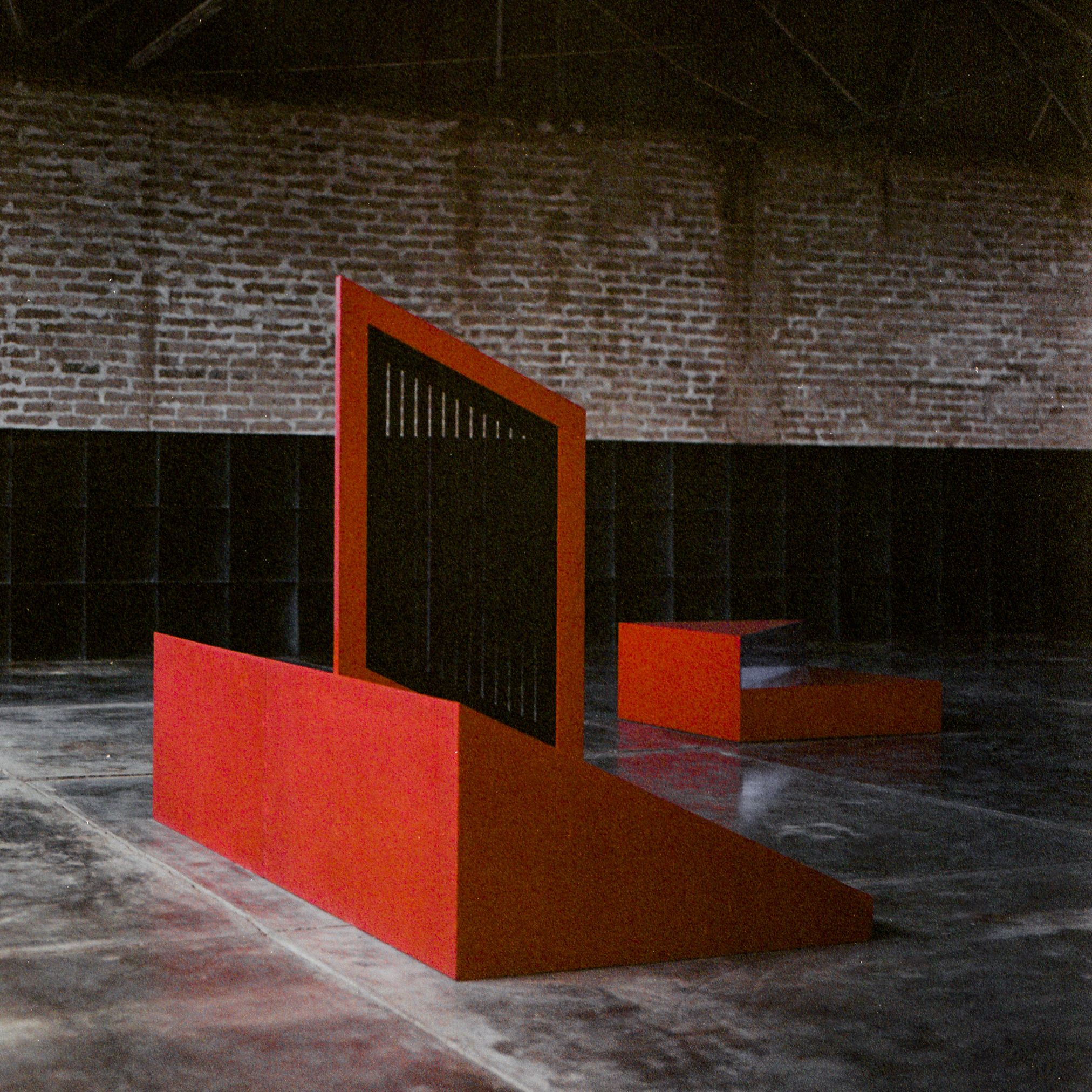

Donald Judd was a prominent name in the art world when he decided to ditch New York for the starry West Texas desert. It was 1971, and Judd was determined to get as far away from the art world where he’d made a name for himself in the early 1960s as a wildly prolific art critic and later an artist working with proportion, light, space, and three-dimensional objects. He disliked the way museums handled the installation and transport of his pieces, at times mistaking his works for shipping containers. So he looked at a map, found one of the least populated places still in America, as his daughter, Rainer, told The New York Times, and packed his belongings. Along the way, he snapped up dozens of notable spaces in and around Marfa, including a full city block and two large airplane hangars, remaking them in his singular vision in the process.

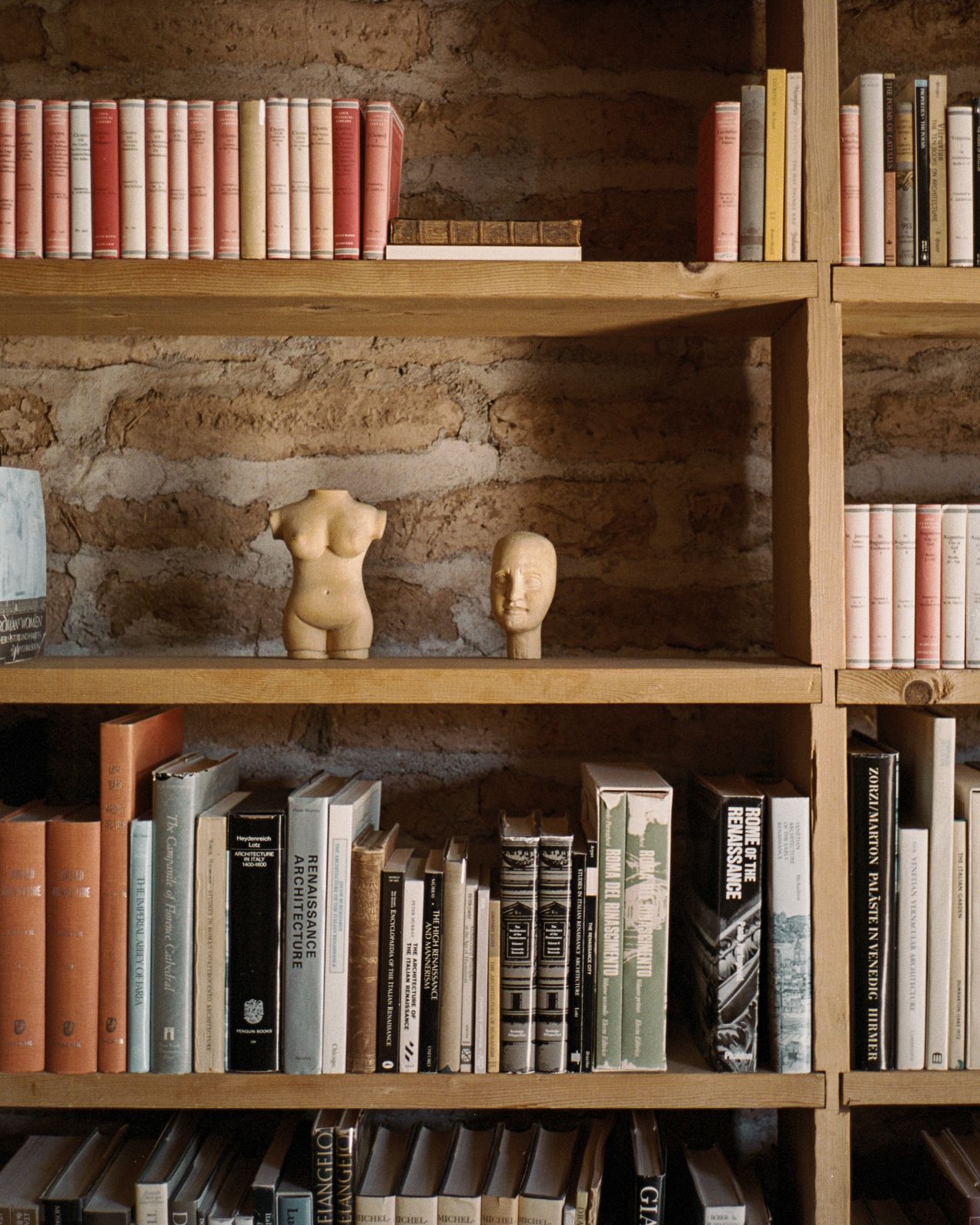

Judd, who passed away in 1994, remains a driving force in contemporary art. One need only visit Marfa to understand why. Here, 10 of the American sculptor’s enigmatic living and work spaces, including his personal library with more than 13,000 books on a range of subjects including art, astronomy, literature, and philosophy, are open by appointment through the Judd Foundation. The Chinati Foundation, which opened to the public in 1986, presents a compelling program of public tours, artists’ residencies, special exhibitions, lectures, performances, and publications that seek to further the dialogue Judd passionately pursued between art, buildings, and the natural environment.

MATERIA’s Editor-in-Chief, Sarah Len, visited Marfa to see Judd’s artwork firsthand and came away with a deep understanding of the ways Marfa shaped his practice. Here, Rainer Judd, Judd’s daughter, a filmmaker, artist, and president of the Judd Foundation, and Chinati’s director, Caitlin Murray, spoke with MATERIA about preserving his legacy.

Sarah Len: Rainer, what do you remember about your father’s work as a child?

Rainer Judd: I remember getting lightly in trouble for running through a plywood box wearing sneakers. But I remember so much warmth. From wood surfaces, from fires at night, from good food, from candle light, from colors—colors all the time, in food and on metal. So much beauty all the time.

SL: In recent decades, Marfa evolved from a remote town to a cultural destination. Rainer, take us back to the time your father discovered this town. What drew him to the desert?

RJ: This was a popularity created by different waves of people other than Donald Judd and Judd Foundation, after Don’s passing. He was never an advertiser and would have not been supportive of promoting Marfa as a tourist attraction. He was focused on work and creating a depth of experience—art, architecture, dark skies, and land preservation. He was interested in the land remaining undeveloped and chose Marfa for its lack of popularity and lack of population.

SL: The desert certainly has an undeniable allure. Rainer, how do you think the environment helped inform his creative process?

RJ: It expanded the scale of his work, markedly. He made a work in 1980—it is 80 feet long—which was made after his first few years living here full time (with travel, of course). Only he can speak to his creative process, but I know it expanded, as he had more room for everything—ideas, making furniture, renovating buildings. He, like many scientists, believed that what you observe matters. The more he could make and observe, the more ideas he could have.

”The responsibility of each generation of any culture to continue forward the important work of stewarding resources so that all can live a bright, thought-filled, well-fed life in the deeply respected natural world. It is no joke and it is not complicated.”

– Rainer Judd

SL: Being so close to the Mexican border, I imagine your father also developed an admiration for the neighboring country.

RJ: He loved Mexico. He hoped to convince my mom to give birth to me, their second child, in Baja, Mexico, so I would be a citizen and he could buy land there. She rebelled, as was her right, and birthed me in New York City, near her mother and sisters. Mexico was his first choice. Marfa was his solution to being American. He searched all over, and he liked its vastness. He loved its beauty, its scale, the town, the ranchers, the Mexican-American community, and its architecture.

SL: Growing up amidst your father’s creative endeavors, how do you think his artistic philosophy has shaped your own approach to art? And who do you think influenced your father the most as an artist?

RJ: He had a philosophy that was for life, and art was not isolated from life but linked with everything else: the beauty extending all around in Marfa from detail to expanse. The dignity you seek you give to others on a daily basis. That science matters (and I mean, really, really matters). The responsibility of each generation of any culture to continue forward the important work of stewarding resources so that all can live a bright, thought-filled, well-fed life in the deeply respected natural world. It is no joke and it is not complicated. It is only people who seek enormous profit who confuse the basics. I once asked him why nuclear weapons existed, and in short he said money.

SL: The foundation’s engagement with sustainability and the environment is worth noting. Caitlin, how does the Chinati Foundation incorporate these values into its initiatives?

Caitlin Murray: A recent undertaking––the replanting of cottonwood trees on-site––is a good example of our commitment to maintaining a healthy landscape. East of the 15 untitled works in concrete, Judd planted a row of cottonwood trees that runs parallel to a small creek bed. The cottonwood trees that he planted (around 1981/1982) are native to North America, but they are no longer well-suited to our region and its climate. More than 20 new Rio Grande cottonwoods will be planted at Chinati in October, and this massive undertaking will improve the health of the site while preserving Judd’s vision for it.

”In his essay ‘Marfa, Texas’ (1985), Judd writes: ”Proportion and scale are very important. In contrast to the prevailing regurgitated art and architecture, I think I’m working directly toward something new in both.”

– Caitlin Murray citing Donald Judd

SL: Seeing Judd’s 100 untitled works in mill aluminum is quite an emotional experience. Caitlin, what do you think Judd wanted his viewers to feel when they saw these pieces for the first time?

CM: In his essay ‘Marfa, Texas’ (1985), Judd writes: “Proportion and scale are very important. In contrast to the prevailing regurgitated art and architecture, I think I’m working directly toward something new in both.” While it is difficult––impossible––for me to name a desired emotional response to the 100 untitled works in mill aluminum, I believe he wanted viewers to experience the wholeness of this ‘something new’ with both thought and feeling.

SL: Rainer, how do you see Marfa’s art scene, and your father’s contributions to it, evolving in the coming years?

RJ: Judd Foundation is now the “grandfather” organization of the arts organizations, and we have a responsibility to share in the community’s challenges and facilitate opportunities that benefit the people who live here and the land that we all love. But the real great-grandparents are the many indigenous people who were here for thousands of years before us. Their advanced cultures are still being studied by local descendants [along with] the rich archaeology of the area.

SL: Cailtin, what do you think the future holds for Donald Judd’s legacy?

CM: Chinati began with artists determining the placement and context of their work, and we remain steadfast in our commitment to this fundamental tenet. Caring for these works and the buildings that house them remains a priority … We will continue to grow our community of artists, and we hope to increase accessibility to this network through new lectures, concerts, readings, performances, and workshops.

SL: Rainer, what would you like your father’s legacy to be for artists, designers, and art lovers?

RJ: To empower them to take better care of each other than his generation and the current one. To make art. To make what they want.

A special thank you to Dobel Tequila for making this interview possible.

Please visit the Chinati Foundation and Judd Foundation to schedule a tour and discover their ongoing program.