TROPICAL MELANCHOLY, A CONVERSATION WITH DANIEL LEZAMA

Photography by Noel Higareda

Artwork images courtesy of Galería Hilario Galguera

Mexican artist Daniel Lezama merges the chaos of modernity with the indigenous past. Through his large-scale works he incarnates a neo-baroque vision of metaphysical beauty and absurdity. In mixing the mundane with sacred rituals and divine enlightenment, he challenges our conception of history and makes us step into the territory of fiction.

MATERIA visited Daniel Lezama’s studio in downtown México City to take a glimpse at his creative process.

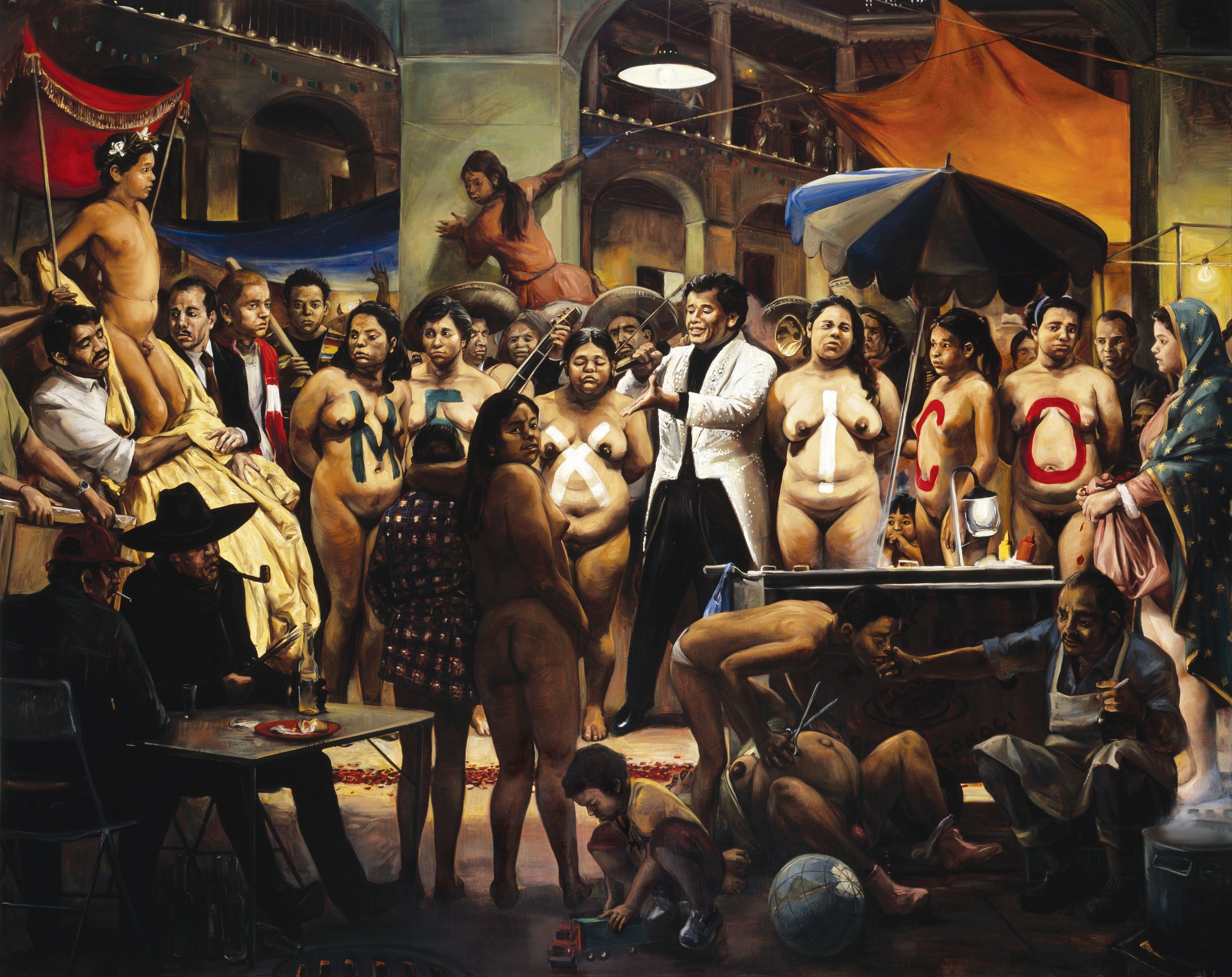

THE GREAT MEXICAN NIGHT, 2005.

ALEPH MOLINARI: Did you have a formative religious or ideological upbring?

DANIEL LEZAMA: I was raised Catholic, but I didn’t grow up with the experience of any religion. With time I became an atheist but without denying the possibility that something else exists. What is worth to me exists during the time we are alive. Not before or after. Deep down, however, I’m an existentialist.

AM: And a mystic?

DL: No. My father was a mystic. He had a mystical temperament and contemplated transcendence. He read about religion, theosophy, and Kabbalah. At the same time, he was passionate about politics. He was a complex man whose opinions were informed by an ideological vision. I inherited that complexity but directed it towards other things. In reality, I consider myself a hedonist. A reflective one.

“In some ways. When I paint, there is nothing more important than what I’m painting in that moment: the painting itself. If you think about something else while you are creating a work of art, you end up simply illustrating an idea. And I never want my paintings to be solely illustrations. Because my paintings are created with an aura of mystery and Hermeticism, there’s an inconclusive and inaccessible part of reality that is present in the work. I do things that I do not fully understand and in that process I arrive at new questions. “

—Daniel Lezama

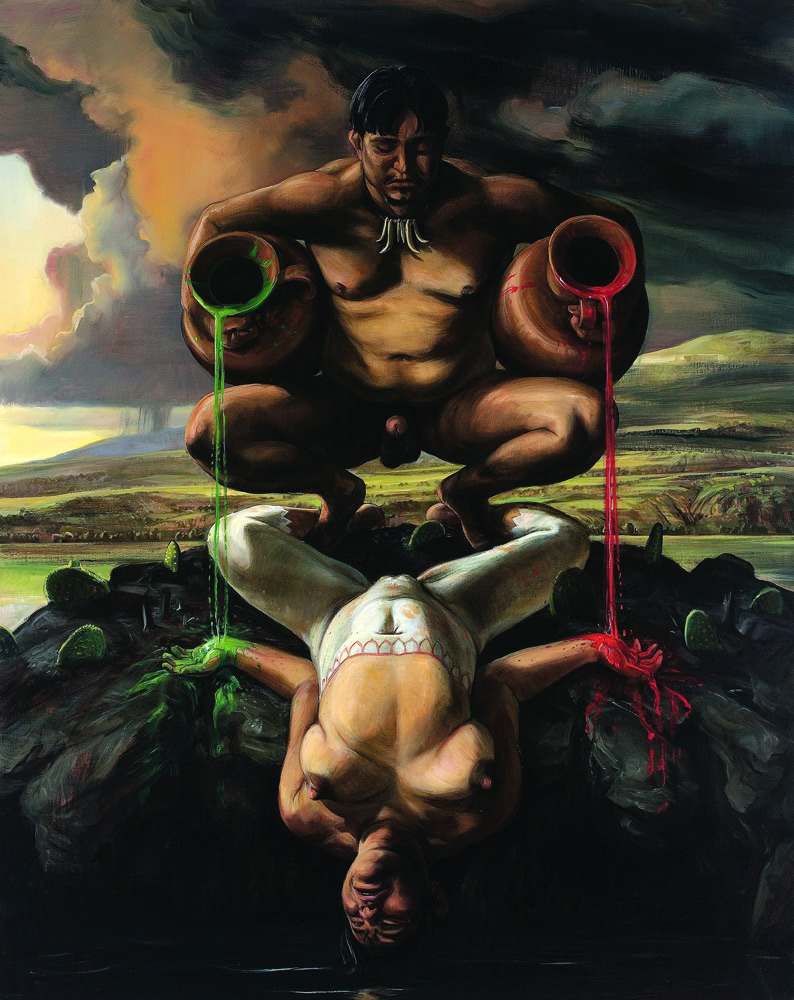

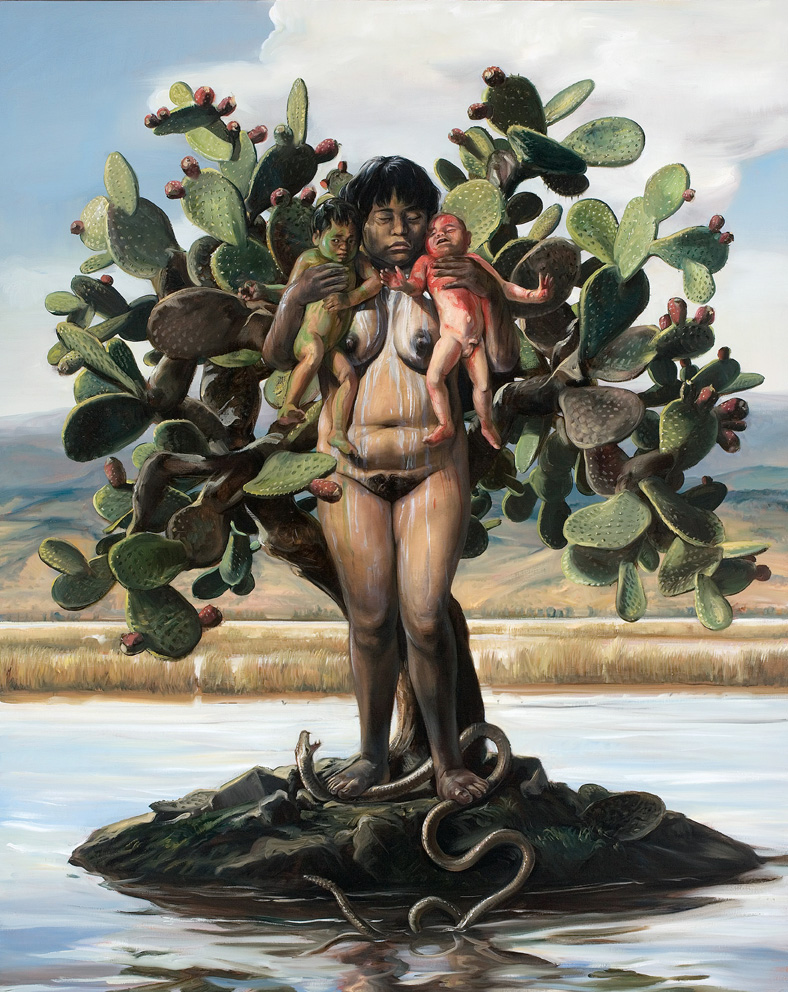

THE THREE GRACES OF ZANZIBAR, 2009.

AM: Do traces of that mysticism manifest in your painting?

DL: In some ways. When I paint, there is nothing more important than what I’m painting in that moment: the painting itself. If you think about something else while you are creating a work of art, you end up simply illustrating an idea. And I never want my paintings to be solely illustrations. Because my paintings are created with an aura of mystery and Hermeticism, there’s an inconclusive and inaccessible part of reality that is present in the work. I do things that I do not fully understand and in that process I arrive at new questions.

AM: So painting is a way of finding the answer to these questions?

DL: Yes. Art is a capricious system of questions and answers. It constantly generates new questions that in turn lead to partial answers in the form of a future painting, a future novel, a future work of art. The process of artistic creation works in a similar way, regardless of the medium.

AM: Does this become your way of dialoguing with the world and mediating reality?

DL: Absolutely. It’s a mediation that manifests physical outcomes that are outside of me. I see a painting and I don’t recognize where it came from. It’s like having a child and seeing him grown up—you recognize an independent being. The art object has a weight of its own that’s separate from the artist and their intention. I’m skeptical of intentionally schematic visions of art, which have come to dominate the 20th and 21st centuries.

AM: How are the themes that you grew up with integrated into the personal mythology that is expressed in your work?

DL: My visual imaginary could be defined in two ways. The first is what I want to see. The second is what I can’t see and have to invent. As a child, I would see the paintings of Rubens and Caravaggio, and I would fantasize about something else happening in the scene. That’s how I started to paint things that didn’t exist and which I had to invent, to give these images a new path and a new meaning.

AM: Did your process of painting begin with representing the reality in front of you?

DL: I began painting from reality and still do so as an exercise. Everything I do now is an invention. My creation stems from my mental archive of reality, that is the starting point. I don’t work with a photograph in my hand. I go into my inner vision.

AM: The imagery in your art is informed by pre-Hispanic themes and of the formation of México as a nation. Would you say that in that process you create a new mythology.

DL: In the beginning of my career I had that approach. I used to deconstruct the heroes and re-make them using sentimental motifs, challenging the idea that the history of México is a mise-en-scene and that painting itself is a mise-en-scene. Hence, the history of México is really like a painting.

AM: You are re-creating an alternative version of history?

DL: Yes, an unofficial version that is at the same time a version of the “real” history. It is the Lezama version. I am counter-proposing a personal and authentic vision. It is what I imagine when I leisurely think about the rich history of México. I want to see the physical and the terrestrial, the feminine and the tactile, not just the patina of the ideological.

AM: Is there also an aspect of portraying suffering and the visceral?

DL: I try to convey a joyful vision, not one of suffering. It can be a corporeal vision, evident in the terror of living and dying, in the joy of its physical and spontaneous character, its unconsciousness, its desirable and undesirable darkness. I am not a painter of violence. I am empathetic with images. You won’t see black and white, morally binary, characters in my images. Yet there will always be a territory of transition, even in the macabre situations I paint.

AM: There is a moment of transcendence and transformation in the characters. An illumination, like in your painting of the woman with the soldering mask on the ground, a form of femme en extase. A moment where the soul wants to leave the body. This is something that has always attracted me to your work.

DL: I agree with that, although I don’t consider myself a painter of suffering or joy. Suffering is an ex-stasis, a moment of epiphany that can be painful and joyful at the same time. It is the recognition of human limitations. One of the elements that define my work is the emotional atmosphere, which is quite complex.

AM: Does it also function as a mirror of your emotions?

DL: Certainly, but it is also a construction of myself. What is being painted is an elaborate me that is not the real me. I have everything and nothing to do with what I am painting. When one of my paintings pulls you towards a new territory, that is no longer me. It is the painting that has the power. I just made it and left, like an irresponsible father who leaves his children abandoned to the world. My paintings all vibrate in their own ways, and in the end, they are proof of the power of art. It is part of the process of creating an object that is part of that transcendence, of this bastard religion.

“…painting is a delight. You do it for yourself, and that is hedonistic. It’s an onanistic process. There couldn’t be anything more hedonistic than creating your own pleasure. That is a miracle which I am thankful for, to have in my hands the power to satisfy myself through a work of art. When you do it for yourself in a way that is brutally honest, something of that is transmitted onto others.”

—Daniel Lezama

AM: I find it curious that you call yourself a hedonist even though much of your work is about transcendence and the moment of creation.

DL: Yes, but painting is a delight. You do it for yourself, and that is hedonistic. It’s an onanistic process. There couldn’t be anything more hedonistic than creating your own pleasure. That is a miracle which I am thankful for, to have in my hands the power to satisfy myself through a work of art. When you do it for yourself in a way that is brutally honest, something of that is transmitted onto others.

AM: Are there moments when your work reveals your vulnerability and exposes something that is perhaps too intimate to show?

DL: Well painting is a form of filter, a backdrop. You enter the territory of fiction. And it will ultimately dissociate from you. And the territory of fiction is a game, a playground where you can play with war, death, violence and destruction.

AM: But in the end everything is fiction, as in your conception of history.

DL: Yes, and precisely for that reason it would be absurd to judge the creator for the result. A serial murderer kills but can also paint flowers; I plant flowers but paint murder scenes. There is no congruity. The work is not a psychological document of my madness, it is a document of a process that is beyond myself. It transcends and separates from its creator. For me, the artist becomes a shaman who guides images from one dimension to another, from the unconscious to the conscious.

AM: So the artist becomes a medium?

DL: Yes, a portal from one world to another. But this also leaves artists in an indefensible position. As a creator I don’t know where the ideas come from or why. I just open up and unconscious images pass through me. I don’t control how they move. I need to create that portal so that what needs to come out can come out. Carl Jung defined this as the collective unconscious. I believe every society has latent archetypes in their unconscious with which they create community and culture. At the same time, there is a metaculture, where the universal archetypes are the same. They share a nucleus of the imaginary and the spiritual that come out at the moment of creation.

AM: I am interested in how you integrate the iconography of your youth into your paintings and how those images evoke universal archetypes.

DL: The imaginary with which I grew up gave me tools to build my vehicle, which is painting. The rest I went on discovering myself. As a child I lived between France, México and the US. At the time I was afraid of México because I didn’t understand it, it felt too emotionally charged. I didn’t understand the indigenous tribes, the tropics, the legacy of Catholicism. Later in my adolescence, it was my libido that allowed me to finally embrace México and take the bull by the horns. My environment and its complexity started to arouse me. Conversely, all the things that were light, fresh, and rational became boring, and I began to be seduced by the heavy, the earthy, the difficult to understand.

AM: Is painting in a way a fetish for you? Or is it a way of exploring your fear of México?

DL: The themes in my paintings are my fetishes. In reality, México is my fetish and painting is a way of managing my fetishes. Some of the most reflective parts of my work, like the works in the period when I made La Madre Prodiga, came about in that way. Initially I wanted to be a writer, not a painter. My grandfather had library comprised of all Mexican and 20th century Latin-American writers, with a collection of erotic literature. I read and read and read. That’s when the machinery of my world was set into motion. I then began to build images and capture that which I did not understand.

THE PRODIGAL MOTHER, 2008.

AM: What’s your approach to turning historical and literary reference material into a painting? Do you begin by writing, sketching, drawing?

DL: I used to do elaborate sketches and drawings before copying them onto a large-scale canvas. It was bothersome and boring and it blocked other possibilities. For La Madre Prodiga, I did twenty-five sketches in pencil and one sketch in oil. That allowed me to paint quickly and effectively, but left me unsatisfied. One day I said, “Enough! I’m fed up with sketches.” Now, I work directly on the large canvas. I like it when the painting reveals new things to me.

AM: Tell me about the light that appears in your paintings, that supernatural light that shines out of the characters. Is it a form of illumination, of transcendence?

DL: It’s a visual trope that refers to energy and to the exceptionality of the character. In my work there are characters that are filled with light that emanates from their mouth, their navel, or their sex. The light separates the characters from the place where they are situated, like the sensation of an ectasis or a power that is being manifested.

AM: Are you constantly reinterpreting history and fiction?

DL: My work is not to paint paintings, it’s to invent images. Take Jeff Wall for example, he makes massive installations in order to take large-scale photographs and show the scenography that he wants to show.

AM: Yes, in reality Jeff Wall is a painter who creates impossible scenes through photography. From the digital process of assembling images in the late 1980s, to his way of editing digital images as brushstrokes on the canvas.

DL: Yes, and in the same way I generate imaginary landscapes, a series of complexities that cross disciplines. My work, like Jeff Wall’s, is very theatrical. Jeff Wall is a painter but he doesn’t paint, he creates images. So what is important, to smear oil paint on a canvas or to create images? I feel that it’s more relevant to create images. But in my case, to apply oil paint is essential to doing it right.

AM: Do your references to art history emerge on their own?

DL: I call it the Tool Box, as John Berger coined it. Although he said it critically, in the sense of being conditioned. Art is a tool box that grows vertiginously. Jeff Wall or Cindy Sherman would be unthinkable a hundred years ago. Or Damien Hirst and Mat Collishaw. They are painters who are post-painters. What really matters is building images.

AM: And has your work attracted controversy for the way you depict the indigenous cultures within the history of México?

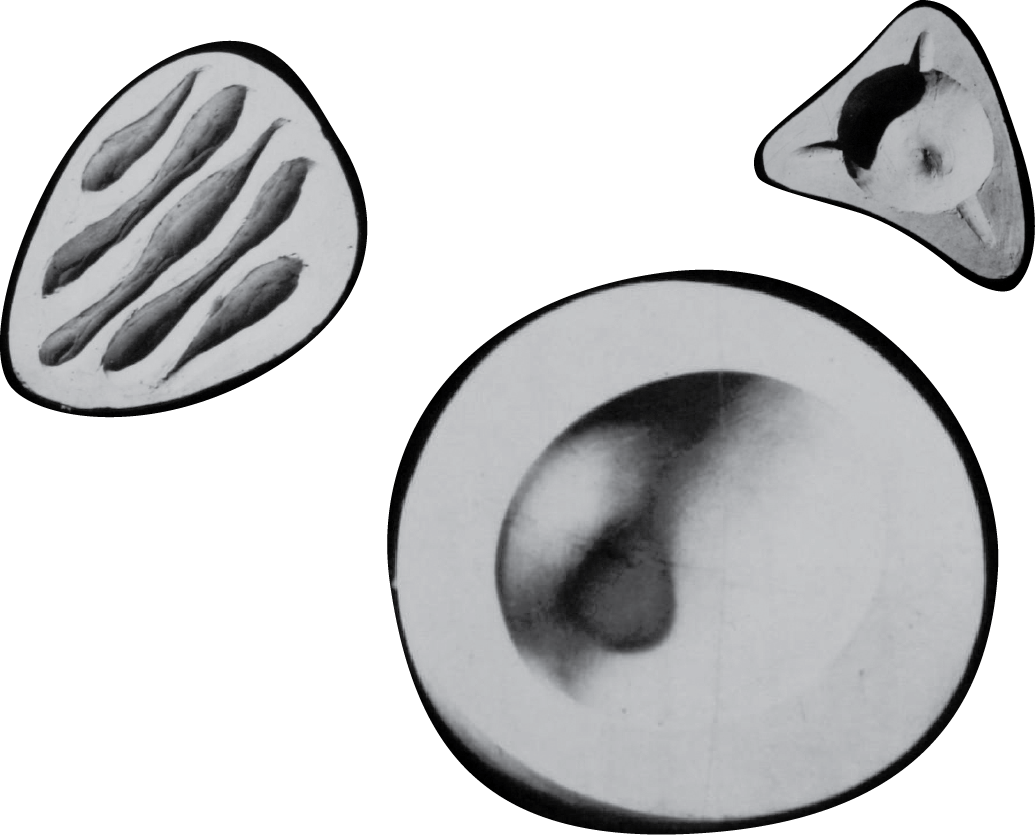

DL: Not really, especially in comparison to other artists that have made less provocative works and have had a harder time. Like when Rolando de la Rosa exhibited his Virgen Marilyn at the Museum of Modern Art in México and they almost burned down the museum. Or when Chris Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary, that was made with manure, was exposed at the Brooklyn Museum and it was censored. These provocations are badly received. And I feel like they are warranted, because a provocation requires an answer. I have made many obscenities in painting, but I have always done them with empathy and respect. For example, my Virgin of Guadalupe, which is a vagina. And conversely, the vagina is the virgin, anatomically speaking. Her head is the clitoris, the folds of lights and the mantle are the exterior lips. Her dress is the interior part of the vagina, below is a shadow that refers to the vaginal orifice and under is the perineum in the shape of an angel. Everything is a subliminal image of the vagina. In the image you see your mother, you see the origin. The origin of the world is not Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde, it’s the Virgin of Guadalupe.

AM: It’s without a doubt a symbol of colonialism as one of the first images to hybridize two cultures and mediate two worlds—an indigneous man who goes to the mountain and receives a holy vision of a virgin who has darker skin.

DL: Yes, and the story behind the image of the virgin is fascinating. In fact, Juan Diego was an indigenous noble from a divine caste. There was a very strong alliance between the criollos and the Indigenous principates that continued until the 18th century. Coming back to the image, the controversial image is that which wants to elicit a negative reaction. When I made that painting of the virgin, I didn’t think about it as a provocation, but as a statement of fact. That’s what it is, and everybody knows it but doesn’t say it. When I exhibited the painting, it was seen by thousands of people— groups of children, teachers, religious people—and nobody got offended.

AM: Do you feel that it was because of the intention behind the work?

DL: I’m just saying what everyone already knows, and I’m saying it with affection and kindness. With a degree of obscenity, but without aggression. What is uncontestable is that I’m controversial, but I have never had a controversy in over twenty-five years. There are no discussions, insults, or tabloids. Nothing. It’s quite paradoxical.

AM: How has the subject matter in your work evolved over the years?

DL: I’m going through the same thing that happened to José Emilio Pacheco. You love a country and then you become disappointed by it. At the same time, you continue to love some things you loved about it. México is a marvelous rollercoaster—sentimental, emotional, social, political, and economic.

AM: It began as a story of fear, then of discovery, then of love and passion and then…

DL: Pain. But it’s something that does not appear in my work. As an artist, you start concentrating on the poles of your emotional attention that are below the surface of what you call México. The fascination goes toward the personal and the intimate, toward the depths of the subconscious and the universal, but it’s always based in México. There is an untouchable territory where what you create continues to be fueled by passion. There is a precious tropical melancholy. You see all the dreams that end up as stones under a tree.

AM: Daniel, thank you for the wonderful interview.

Alta traición,

No amo mi patria.

Su fulgor abstracto

es inasible.

Pero (aunque suene mal)

daría la vida

por diez lugares suyos,

cierta gente,

puertos, bosques de pinos,

fortalezas,

una ciudad deshecha,

gris, monstruosa,

varias figuras de su historia,

montañas

-y tres o cuatro ríos.

José Emilio Pacheco

De Islas a la deriva

(1973-1975)

Colección Visor de Poesía, 1990

High Treason

I don’t love my country.

Her abstract glory

eludes me.

But (this may sound bad)

I would give my life

for ten of her places,

for certain people,

ports, pine forests,

fortresses,

for a ruined city,

gray and monstrous,

for several of her historical figures,

for mountains

(and three or four rivers).

José Emilio Pacheco

De Islas a la deriva

(1973-1975)

Colección Visor de Poesía, 1990

Translation by Dave Bonta

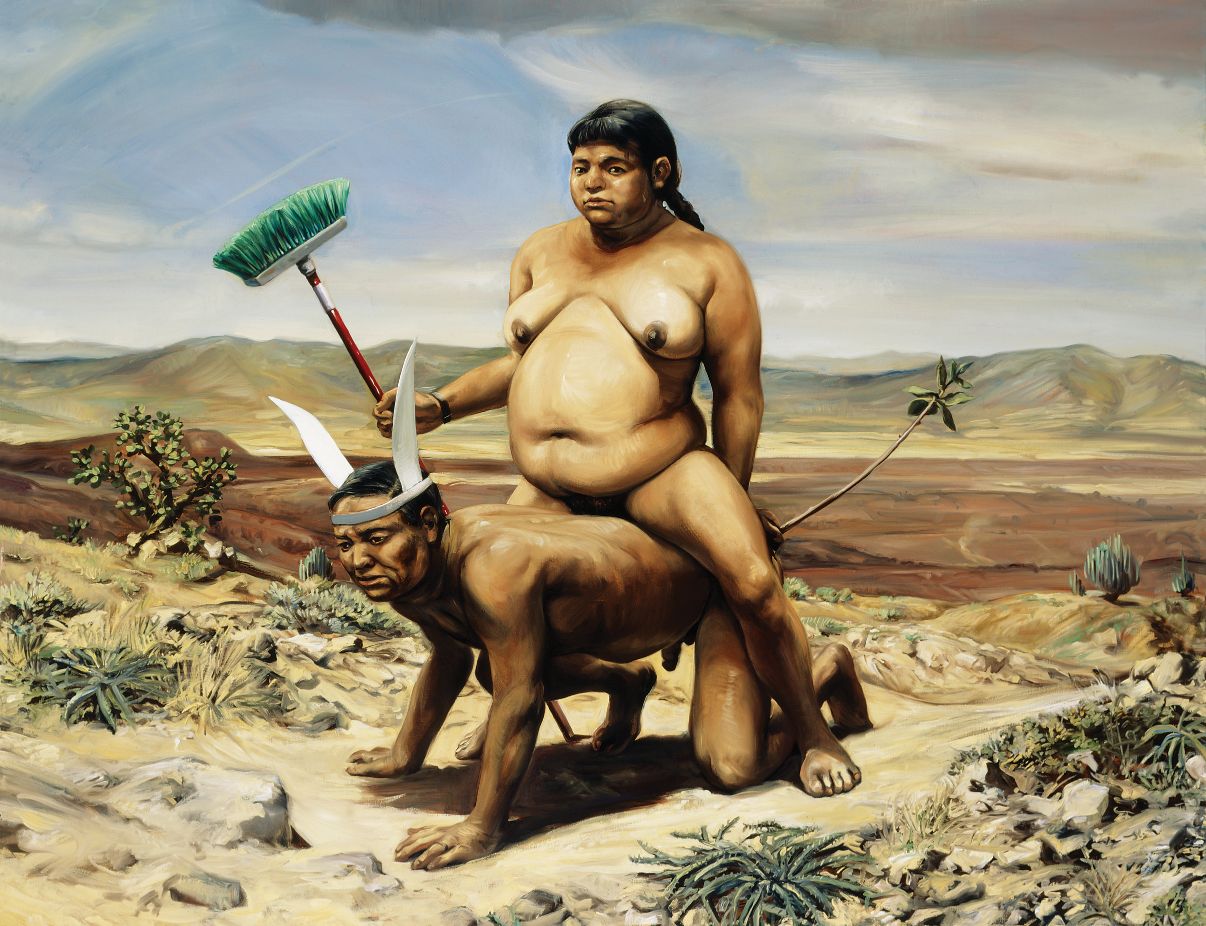

PHILLIES AND CREOLE ARISTOTLE, 2005.

MATERIA would like to thank VaiVén Collectors A.C for facilitating this interview and Galería Hilario Galguera for providing the images of the artworks.