DISCO TEHRAN: THE ANCIENT ART OF THE PARTY

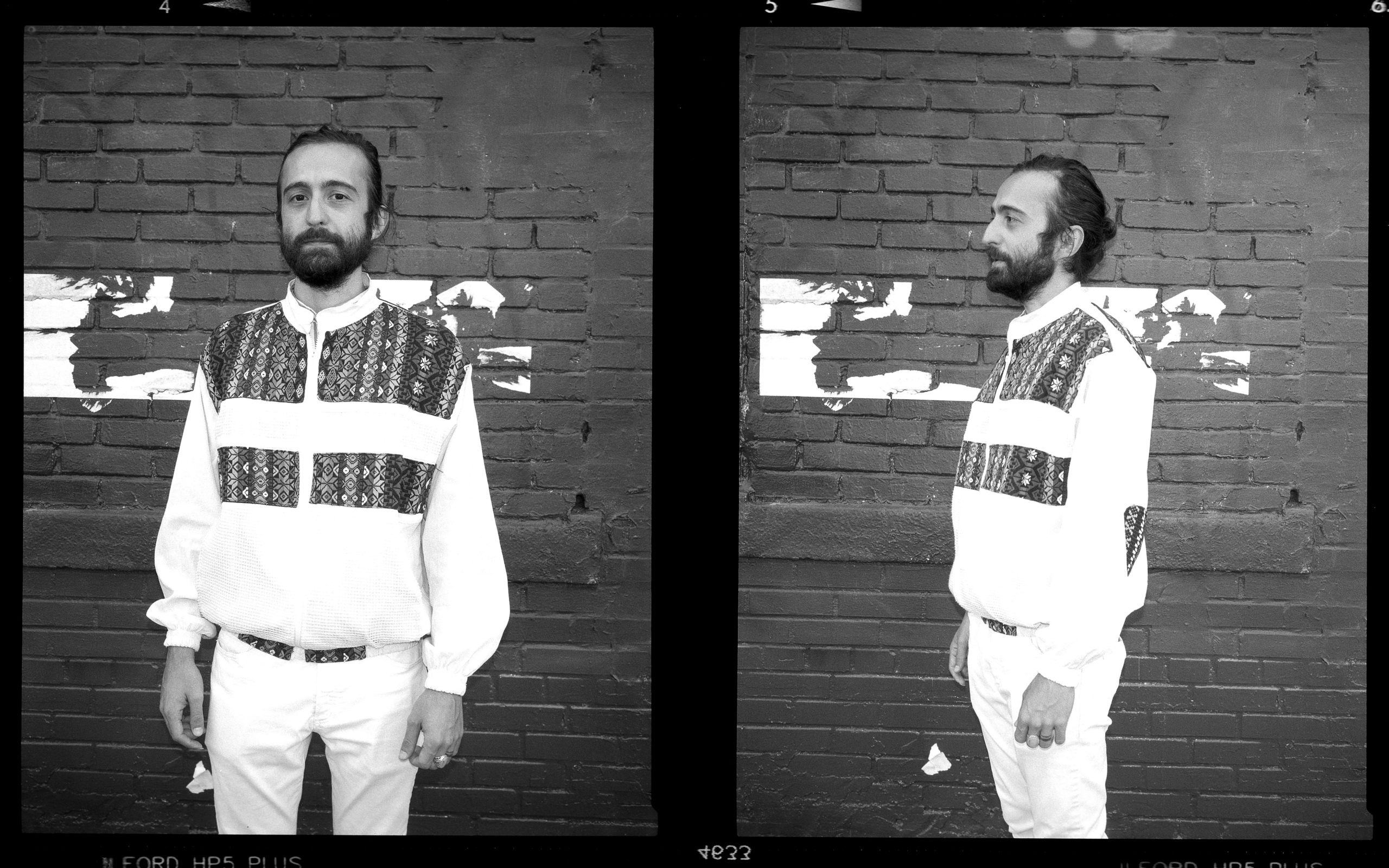

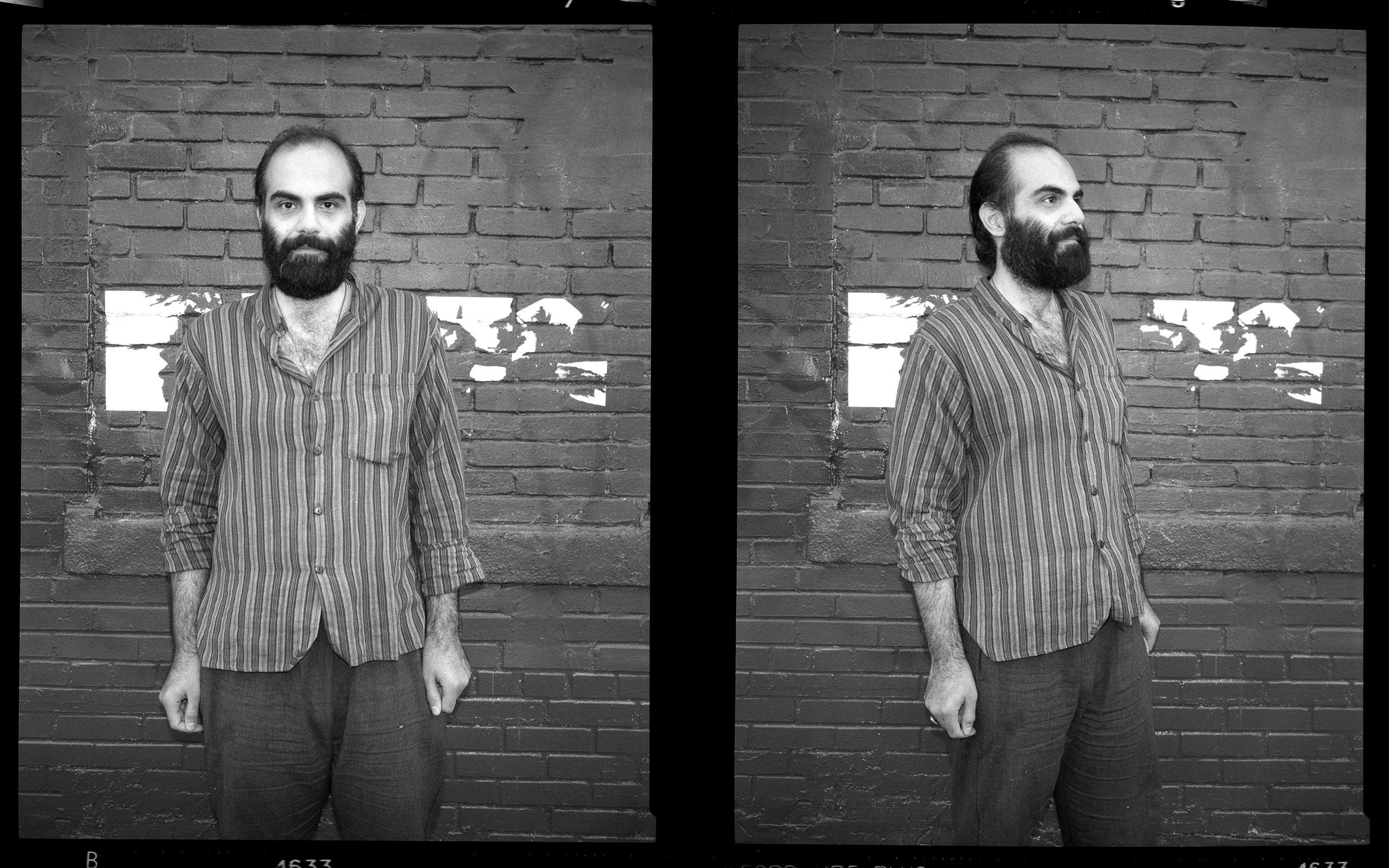

Portraits by John Cornelius

Images courtesy of Disco Tehran

Disco Tehran is a roving multicultural dance party, a dream boat that connects present-day New York City to the bygone era of discotheques in 1970s Tehran. Arya Ghavamian and Mani Nilchiani, the creators of Disco Tehran, carefully curate a selection of sounds and musical gems from Iran and beyond. Their joyful dinners, parties, and performances bring people together through a shared sense of home and belonging. Aleph Molinari interviews the dynamic duo to find out how they create intercultural communal experiences and a socially conscious way of partying.

This interview is accompanied by an exclusive two-part mixtape created by Disco Tehran and Aleph for MATERIA.

ALEPH MOLINARI: How did the idea of bringing back the golden era of discotheques in Tehran in the 1970s originate?

ARYA GHAVAMIAN: When I moved from Iran to the US, one of the biggest shocks was my inability to have communal experiences around the events I grew up with, such as Nowruz, the Iranian New Year. It is one of the most multicultural celebrations in human history, celebrated from Eastern Europe all the way to Northern China. Historically, Iran was in the center of the Silk Road and still has that geopolitical space, in the middle of everything. It has a quality that is both ephemeral and transitory. Nowruz happens on March 21st, but because it’s based on the revolution of the Earth around the sun, the hours are different every year.

AM: I love the idea of celebrating an astronomical phenomenon at the time when the stars align. So the project was initially born out of nostalgia for a bygone era?

AG: It was something less conceptual than nostalgia. It was really about yearning to connect and getting people together. It was a lonely experience, not being able to celebrate with everybody. I felt I was going to die of loneliness. When I met Mani, it dawned on us that we could host celebrations ourselves instead of looking at other people to make them happen. Mani and I would host gatherings and dinner parties at my apartment, and I would cook Iranian food.

MANI NILCHIANI: We felt there was a massive vacuum, a need. There wasn’t a place to celebrate and to share the intergenerational lived experiences of Iranians in diaspora. Gradually, the idea around crafting a communal experience started to form. People were showing up to our parties and we began hosting bigger events. First, we took it from Arya’s apartment to a dive bar where a friend was bartending. Then, he invited us to take over on Monday nights and that’s when we made Disco Tehran public.

AM: So what began as a dinner party then became a party. How did the musical selection evolve?

MN: Playing music was always at the heart of it. I would bring my instruments to play and Arya would spin records. There was a beautiful overlap in the way I was exploring music by incorporating elements from Iranian folk music into rock-n-roll and indie rock. I was integrating grooves that were rooted in regional music into sets that I would play with my band. Seeing how the groove connected people, we immediately knew there was a flame. And if we kept curating the right kinds of sounds, we could create moments of celebration where everyone could find something. Like Arya, I too was looking for a piece of home, for a sense of belonging, and that became the core of the [Disco Tehran] experience. We had people who came from Eastern Europe and Brazil and everywhere in between saying, “That song you played reminded me of home.” The idea was to create a moment where people could find a sense of belonging, no matter where they came from.

AM: It’s a way for people to connect with their past, with their lived and remembered experiences of their home. Do you see music as a way of processing the trauma of leaving your society and feeling dislocated, as is often the case with the Iranian diaspora?

AG: A lot of it has to do with the nature of Iranian poetry and its timeless presence. Our music developed from our poetry, and for a long time, it was taught in a direct teacher-to-disciple method. We call it “heart to heart.” It means that every sound and gesture once belonged to a teacher you never met. Reading a poem written in the 12th century by Omar Khayyam still makes you feel like “Oh god, there is someone who gets it.” Growing up with this perennial culture, I’m always working portals into other timelines, other worlds. It’s mainly for the joy of discovery; maybe some healing comes from it too, but I’m not there yet. What I enjoy is sharing an emotional connection. Today it’s music, tomorrow it’s cinema, maybe one day it will be something completely different.

MN: Music has the power to connect people around shared experiences and create deep bonds. I find these bonds to be empowering and healing. The idea of the throwback has always been at the heart of Disco Tehran. The world we keep referencing is a parallel universe of the nightlife in the 1970s clubs and cabarets of Tehran. That was the experience that our parents had when they were young. They would go to cabarets where bands would fly in from Italy to play the tunes of the day. That timeline stopped at the end of the 70s when the majority of artists emigrated or stopped working because of the revolution in Iran. So we thought, what if we started recreating that timeline, picking up where Iran had left off and imagining what that Tehran nightlife would look like in New York City in 2018. To see how we could recreate that sense of togetherness across different cultures was our guiding set of ideals. Arya uses the phrase “Dream Boat.” It’s a dream boat that connects New York to 1970s Iran.

“Music has the power to connect people around shared experiences and create deep bonds. I find these bonds to be empowering and healing.”

– MANI NILCHIANI

AM: Disco Tehran is doing something similar to what Barış K did in Turkey, bringing back the music from the 1960s and 1970s that was lost or forgotten. You are doing the same with Iranian music, bringing back that era of cultural cross-pollination when music from the outside world blended with folk and traditional sounds to create new hybrid sub-genres. What are the influences and references for this dreamboat?

AG: Growing up in Iran, I wasn’t really connected to many of the Iranian songs that we now play at Disco Tehran, mainly because I was attracted to psychedelic rock and 1970s British rock music. Iranian pop of the 70s and 80s seemed vernacular and didn’t hold much value to me, it seemed out of style. After I left Iran and was trying to introduce something of my culture to people, I would unwittingly reference that Iranian pop music. That’s then I realized I had grown to like that music. The culture around us also influenced Disco Tehran, like the Latin Americans, Africans and Middle Easterners in New York City. The question has always been how do we play Iranian pop music next to a track from Kenya, Colombia, or Mexico. If people are able to dance to [William] Onyeabor, is it possible that we do the same for Iranian music? There are Iranian pop stars that sound similar to him, maybe even funkier. That’s the main idea behind the curation of Disco Tehran.

AM: There are other projects like Deep House Tehran and Acid Arab that are bringing to the surface musical hybrids that combine Middle Eastern music with techno, house and acid. What is happening today with the music scene in Iran?

MN: At some point we had to decide how Disco Tehran was going to be situated in relation to the music scene in Iran. Now that we are situated where we are, we can provide a platform to raise the voices of Iranian musicians. There is a big cabaret revival right now that mixes gypsy jazz with cabaret and incorporates romantic Persian lyrics on top of it. It works phenomenally well and it’s the kind of music that is gaining massive audiences as part of the popular revival.

AG: There are many underground musicians and composers and phenomenal female artists working in Iran right now. Like Deep House Tehran, which is a female-led collective created by Nessa Azadikhah. It’s so important, the role of women creating the new music that is coming from Iran. There is also great electronic and classical music being produced in Iran today, with artists like Ata Ebtekar (Sote), an avant garde electronic contemporary composer, or like Maryam Hemmati, Rojin Sharafi, Makan Ashgvari, and Deep House Tehran, a collective that has a full range of artists who work under their umbrella.

AM: So Disco Tehran is not just Iranian or Middle Eastern music, it encompasses world beats. It talks about diversity, migration and the richness of culture that goes past borders. In 2020 you did the project “Stories of Migration” for MoMA PS1 around these themes. Could you tell me about that experience and the work that you created for them?

AG: The idea for the project came from a page called Nuevayorkinos, where they collect stories of Latin American heritage and immigration to New York City. I was inspired by that project and contacted them to collaborate. Shortly after, I co-hosted a session with them at MoMA PS1. We wanted to do a compilation of written stories that talked about a multilayered experience of immigration, from Iran to Germany to the USA, from Bahrain to Colombia and to France. So we posted an announcement saying: “we are collecting stories of immigration.” And stories arrived from all over.

MN: For their Homeroom project, MoMA PS1 was partnering with collectives that were self-publishing zines and publications. And we had previously created zines—risographing, painting, and hand-binding—and participated in independent publishing events to introduce Disco Tehran and the stories and artworks that we had collected. It was a way of exploring what Disco Tehran could do as a publishing platform. So this was an interesting opportunity to bring stories to life and make the project more personal. What came out of that was a beautiful moment of vulnerability through sharing and expanding connections across different cultures, different timelines, different generations. Storytelling is really powerful as a medium, and music-making is also storytelling. The zine came with a mixtape, which we later took to the stage at MoMA PS1. Ultimately, Disco Tehran is a cross-section of stories that culminates in a moment of celebration on the dance floor and on the stage.

AM: How did the social responsibility of Disco Tehran evolve?

AG: It has to do with our experience in Iran. There is a collective historical trauma that as Iranians we keep experiencing, and that we are still processing. A lot of extremely unfair things have happened, but throughout history Iranians have still gone through tremendous lengths to give back to the community. You can’t be an artist in a vacuum and do public work; you are in a space of reciprocity. When you put something positive into the world, you get something positive back. It has become a cultural and historical imperative to give back, from our experience as Iranians and as artists. In 2020, we ran a large kitchen supported by donations from people who participated in our online events. In collaboration with East Village Loves NYC, we were able to provide more than 150,000 meals to food insecure New Yorkers. Our latest party supports the resettlement and advance parole fees for refugees from Afghanistan.

MN: A lot of invisible labor and support goes into Disco Tehran; nothing happens in a vacuum. In the beginning, people would come and volunteer their time or whatever they had. Arya told me something a while ago that has stuck with me: it is key to be detached from the outcome and do things for the sake of the intention. If Disco Tehran keeps growing as a project, it will be a byproduct of putting intentions in the right place, of putting community and the network support at the center. This resonates with people, as do the social causes we support. It brings the right kind of energy, and the right kind of folks to celebrate and support. Disco Tehran is a party where people come to get down and dance, and forget themselves in the context of a larger community.

AM: There is an insider vibe in going to a Disco Tehran party. Is it important to keep your parties underground and secret?

AG: Even though we now have big parties happening in New York, the essence of the parties began cooking and sharing dinners in my apartment. We hosted a secret party and kept it small and we cooked ghormeh sabzi, an Iranian stew. Today, there are two types of parties within Disco Tehran, one is a secret party and the other is a public one. The question is whether it’s possible to host a huge party that is also intimate, to create larger parties that retain the feeling of intimacy.

AM: I learned not so long ago that you can technically host raves in Iran, but everyone has to be seated. I found it extremely bizarre: the immorality of dance but the possibility of cultural happenings. Do you think these limitations create innovative ways of engaging with music and culture?

AG: The parties and performances that happen in Tehran are done either publicly or in private. When they do underground shows they have to pay people off. And the atmosphere is just like a party in New York or Paris, except that it’s stressful because even if people are paid off, at any moment the show might get raided. If the “party” or show is being hosted publicly you need a permit from the Ministry of Islamic Guidance and to abide by strict rules, one of them being that the audience can’t dance. It’s quite frustrating because people really want to dance. Music shows with a permit are not called raves or parties; they are called exploratory research projects. They are usually shown in gallery spaces under the guise of somebody presenting research.

AM: In A Brief History of New Music by Hans Ulrich Obrist—a collection of interviews with Caetano Veloso, Arto Lindsay, Brian Eno, Kraftwerk, and others—one of the main conclusions is that experimental music wouldn’t have taken off without the art scene. It became a place to exhibit and play innovative sound technologies like the synthesizer and the Theremin, and bizarre sound productions were accepted within the context of art and culture. In some ways, limitations can open up new possibilities. Do you think that these limitations might produce something interesting in the long-run?

AG: Creating music in Iran is immensely difficult because of all the limitations around music and culture. It’s even harder for women because they aren’t allowed to sing in public. Although it may seem that having limitations might be beneficial, my contention is that the emotional turmoil and trauma of going through these limitations—and having that stress on your life—far surpasses the benefits. I’m personally still trying to process what I lived through in my upbringing in Iran and even today have a hard time dancing at parties.

AM: When we met in Paris, you told me that Disco Tehran is interested in having a larger presence in Europe. I told you that I think Disco Tehran parties expand an awareness of the richness and warmth of Middle Eastern culture. Are you deliberate in trying to shift negative perceptions of Iran through your project?

AG: Even asking this question means that there is a force—collective thought, imagination, and resources—behind manipulating and representing images. Our country doesn’t have good PR. It’s unfortunate that a culture of such depth and beauty is not in a position to communicate its richness to the world. I don’t personally think about this too much; I’m focused on creating an enjoyable experience for everybody. Thinking about this gives me a high level of anxiety and self-consciousness because you can’t really erase the images associated in people’s minds. All you can do is provide alternatives and present what is not usually seen. I appreciate that people from many different cultures and countries come to Disco Tehran, just to see each other and be in the same space and enjoy the same thing. That is the essential aspect. We just try to do what we think is right, without thinking too much about changing stereotypes. When you announce what you want to do at the outset, it cancels the action. The magic is gone. It’s like a secret, sacred.