CHRIS WOLSTON ON HUMAN CONNECTION AND MATERIAL CULTURE

Photography by William Jess Laird courtesy of The Future Perfect

Temperature’s Rising on view at Casa Perfect in Los Angeles

October 14 through December 2021

Chris Wolston is a multidisciplinary artist exploring the human connection found in material culture. During the pandemic, Chris moved to his Medellín studio full-time where in partnership with local artisans, he deepened the investigation of the physical properties of materials–which span from woven rattan to bronze and aluminium–and the connections between our bodies, the natural world and architectural environments. “In Latin America there’s much more of a focus and relationship with material”. Temperature’s Rising, is a collection of works that pushes the material process to unexpected levels while allowing for new applications and human mastery.

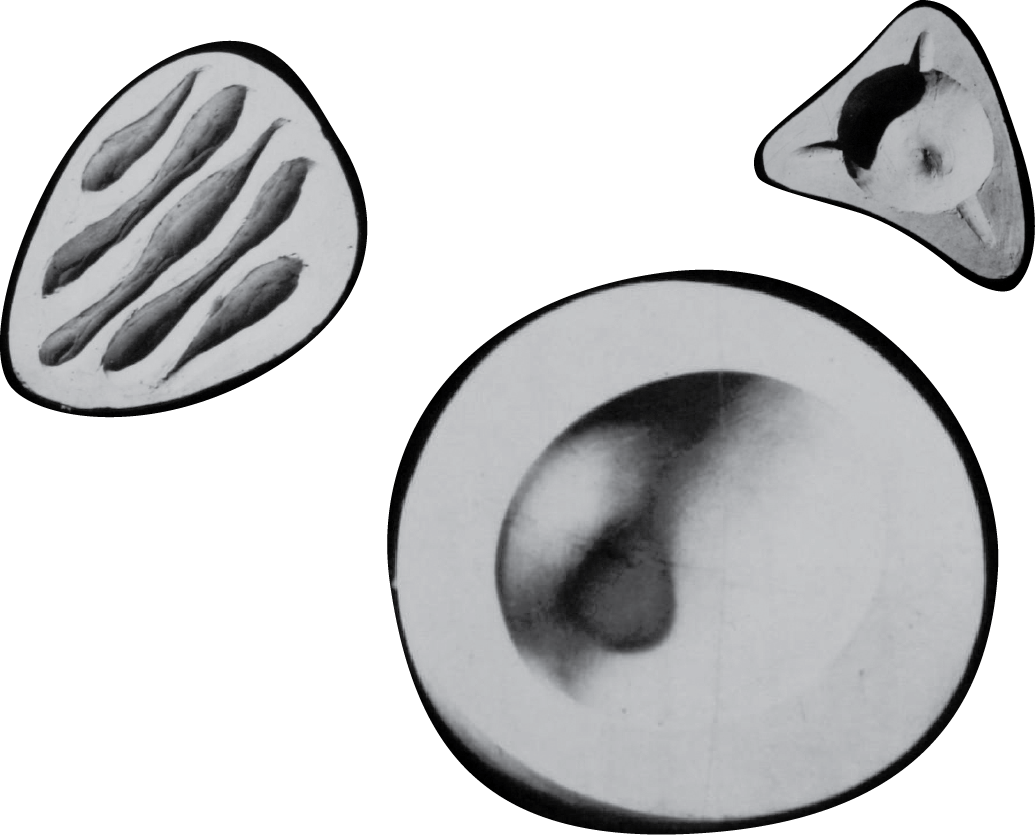

Blending fantasy and realism, Temperature’s Rising takes Chris’s iconic playful anthropomorphic work to the next level with a variety of first –new Nalgona Chairs, his first standing-mirror and first large cabinet which showcase Chris’s mastery of woven rattan on a whole new level, alongside his inaugural sofa signifies his recent foray into upholstery and mixed animal hides.

Chris Wolston gave MATERIA a virtual preview while installing the finishing touches of his new collection at Casa Perfect in Los Angeles. Chris spoke to MATERIA Editor-in-Chief Sarah Len, about his rigorous investigation of materiality and the poetic nature of its greater human connection through the structure and mindfulness of reuse, resourcefulness and elevation.

SARAH LEN: Tell us about your creative journey into materiality?

CHRIS WOLSTON: I received a Fulbright and I selected Medellin because of the incredible relationship between production, materiality, material culture and a living environment. My grant was really focused on what has become the foundation to my studio practice—looking at material that is present in the material culture, the historic past, contemporary architecture, present day artisanal production and how these materials are utilized in various production environments that are then absorbed and valued within the material culture.

Initially, I had a particular focus on terracotta—a material that exists in the earth, it exists in the historic past, in pre-columbian ceramics. The color of the city of Medellin is literally orange, you look at the barrios rising up the mountain and valley and it’s this beautiful terracotta color. The material is used in automated production like brick and everyday artisanal cookware. I explore the re-contextualization of everyday materials.

SL: Rattan is common in your practice. What attracts you in particular to this material?

CW: In Medellin there’s a lot of woven wicker furniture. I find it to be an interesting material because it involves such a skilled human relationship and understanding of material to apply it in a special way. The forms that I saw didn’t really speak to the level of human mastery that are present in the process. So with the forms in this collection, like the cabinet and the chairs I wanted to create sculptural volumes that would transport the material to a different place.

SL: What is the inspiration behind Temperature’s Rising?

CW: So it’s been an interesting working relationship working with the artisans. We work with a profit sharing cooperative up on top of the mountain just outside the city. They are total masters. For example with this cabinet, the wicker is going in different directions, there’s no flat surface, everything is rounded, and they were like ‘it’s impossible, we can’t do it’. I said ‘of course you can do it, you guys are total material masters.’ And so we worked together and came up with a way to make it happen. The work exists in this context here as sculptural furniture, but there is this intensive investigation happening at the studio.

There’s upholstered pieces including the first sofa that I’ve made. In Colombia there is a culture of art collecting, but when it comes to furniture, in particular art furniture there isn’t a place for it yet in the material and the collecting culture. I wanted to create a collection of furniture that utilized these practices that we’ve developed, but pushed the level of material finish beyond anything that I had presented before. The work feels lux, while maintaining the story of how it’s made. We were working in different foundries and engaging in these very hot studio techniques hence, Temperature’s Rising.

NEW NALGONA CHAIRS

SL: How has your time in Ghana and Colombia informed you as a designer?

CW: Ghana was before I entered into Latin America and what was so fascinating was the extent of reuse, recycling and resourcefulness. In the United States, we have access to whatever materials we want. In other parts of the world, there’s less access. The material exists, but in other formats. For example in Ghana we worked with bronze casters who were replicating the maternal sculptural forms of tribes that had existed there for centuries. The material was melted down bolts and screws. The molds made of mud and the product being produced were exquisite. That experience in particular began this investigation of looking into other ways of creating things through exploring materiality. The Kokrobitey Institute in Ghana has since expanded to become a resource center of art and design production with heavy emphasis on recycled materials.

Similarly, in Medellín one of the things that is so valuable and inspiring is the different ideology about wastefulness and reuse. Objects that would be typically thrown away, are not seen as debris or waste. There’s always a secondary use or application. As a maker and artist we look at the world in this way. Within this structure and mindfulness for reuse there’s actually a greater human connection that happens with material and for me there’s something so poetic about it.

SL: What have you learned about collaborating with skilled artisans?

CW: I think that patience is so important. Messing up on the first, second, and third go around, it’s so important to not get discouraged. One thing that I talk about with the artisans is that these pieces push the limits of what they thought was possible. Getting to that place takes time and a lot of trial and error.

SL: How has your work evolved since your first collection?

CW: We can talk about 2016, it was all sandcast aluminum work. Mostly pieces that used a foam burnout technique. One of the things I’m interested in when it comes to a new collection, is pushing the material process to a new unexpected level but also throwing in new applications and materials. With my larger investigation and context of material culture in the city where we make things, it’s important to look around and see what’s there and work with that. The level of lux finishing is important because this work is so experimental—having this level of finish offers an entry way into the pieces and the story.